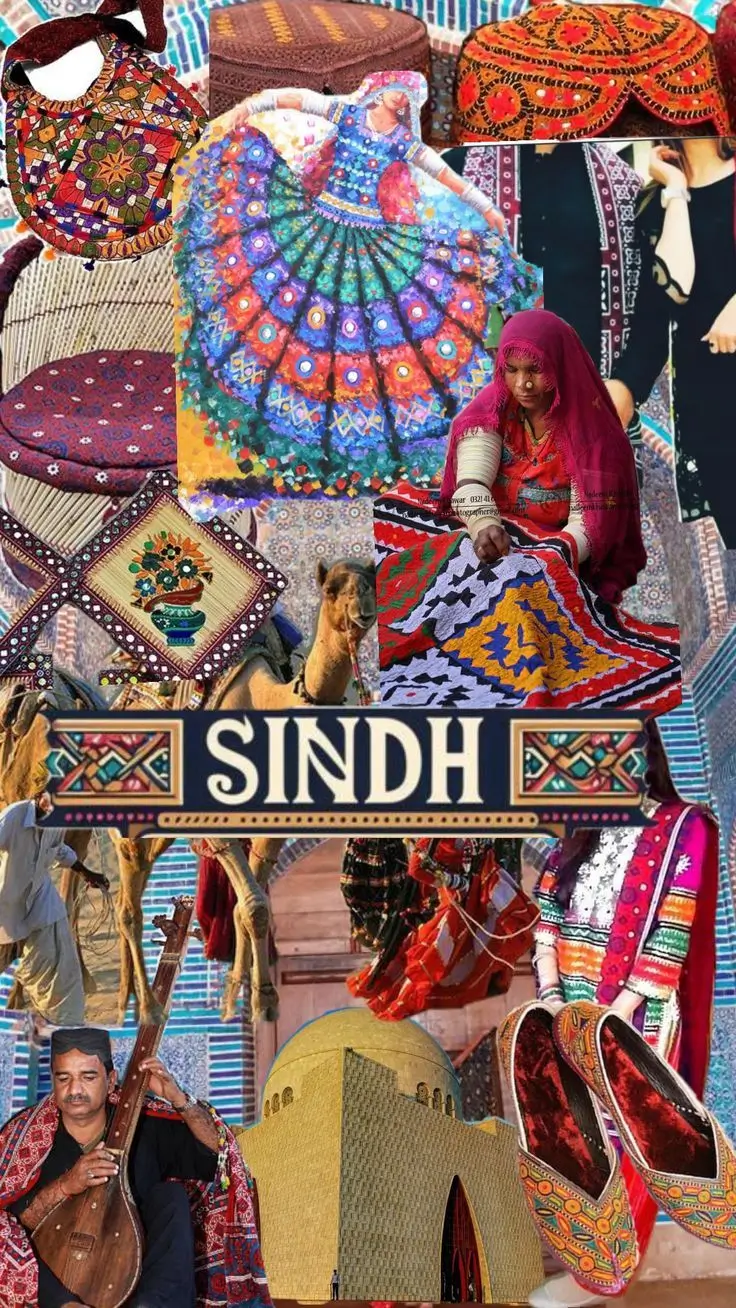

When you step into the rustic charm of a Sindh heritage and Sindhi village, every thread, every woven piece, every bite of warm roti and sip of chai, tells a story — not just of sustenance, but of centuries-old identity and survival. Sindh is more than a region; it is a cultural mosaic, and at its heart lies the craft of its people. Among these, the Rilli quilt, handwoven baskets, embroidered bags, and the culture of roti-chai create a heritage table that is as aesthetic as it is soulful.

Sindh Heritage – Rilli: The Patchwork of Memory and Meaning

Rilli (also spelled ralli or rilhi) is not just a quilt; it is a memory stitched together. Crafted mostly by Sindhi women, Rilli quilts are painstakingly handmade using vibrant cotton fabrics, often from recycled cloth. Each piece is cut into intricate geometric patterns like stars, pinwheels, or diamonds and then sewn with meticulous detail.

Historically, Rilli has been a token of love and legacy gifted to daughters at weddings, used in dowries, or spread over charpais for honored guests. Today, these quilts are slowly gaining global recognition for their artistry.

But despite their rich symbolism, many Rilli artisans work in obscurity, facing declining demand due to mass-manufactured bedding. The need to preserve this Sindhi heritage is urgent, and by simply purchasing or showcasing Rilli art, we help keep these ancestral stories alive.

Roti and Chai: The Heartbeat of Sindhi Hospitality and Sindh Heritage

The charpai outside the thatched hut, the tray of freshly baked roti, the steaming cups of chai — this is not a scene from the past, but the everyday reality of rural Sindh. Chai and roti are not just food and drink; they are an act of community. The shared moments over a meal reflect generosity, resilience, and a simple joy that refuses to be dimmed by hardship.

Whether it is wheat roti made on a clay stove or tea brewed in open air with cardamom and love, Sindh’s roti-chai culture is a comfort ritual passed through generations. It is also a symbol of gendered labor and care — made mostly by women, served to the family, and now celebrated as part of Pakistan’s intangible heritage.

Sindh Heritage: Handcrafted Bags & Baskets: Threads of Identity

From colorful embroidered bags to vibrant coil-woven baskets, Sindhi artisans use local materials like date palm leaves, cotton threads, and recycled fabric to make sustainable, beautiful products. These items aren’t just accessories; they are portable culture each one a marker of the artisan’s skill and story.

Patterns often carry symbolism: stars for guidance, spirals for continuity, and flowers for beauty and fertility. These crafts are often created in small workshops or women’s homes, passed from mother to daughter, generation after generation.

Yet again, mass production and declining markets have marginalized this sindhi craft. Many artisans barely earn a living wage, and the societal value of their work remains low despite their efforts preserving centuries of aesthetic and functional wisdom.

The Bigger Picture: Preserving Sindh Heritage in the Face of Change

Sindh’s traditional crafts from the Rilli to handmade bags were once sold in ancient trade routes reaching Armenia, Baghdad, Cairo, and Samarkand. Places like Hala, near Hyderabad, were once buzzing centers of craftsmanship, home to techniques like:

- Kashi: blue tile work

- Jandi: lacquered woodwork

- Ajrak and Susi: woven and dyed textiles

But now, the art is fading.

Lack of patronage, floods, raw material shortages, and market disconnection have taken a toll. Artisans often struggle to sustain themselves, while their work is reduced to festival stalls or tourist curios. Even though NGOs have stepped in to support these artisans, much more needs to be done. g the craft and providing a thriving income model.

Craft as Resistance, Craft as Revival

Despite all odds, Sindhi artisans keep weaving — not just fabric and baskets, but identity, legacy, and hope. The Rilli remains a storybook of color and care. The roti is still baked fresh, served with a smile. The handcrafted bags still shine under the desert sun.

They are not just objects they are acts of survival, symbols of pride, and bridges to the past.

By supporting these crafts — whether by buying, promoting, or simply learning about them we are preserving an art form, a livelihood, and a unique way of seeing the world.

Let’s not let these traditions become museum pieces. Let’s make them part of our modern story– Shop these Sindh Heritage and its craft on our Store: Nigar Craft

Here are some FAQs based on the provided text, “The Artisan’s Table: What Rilli, Roti, and Bags Say About Our Heritage”:

FAQs: The Artisan’s Table: What Rilli, Roti, and Bags Say About Our Heritage

Q1: What is “The Artisan’s Table” about? A1: “The Artisan’s Table” explores the deep cultural heritage of Sindh, Pakistan, through its traditional crafts and customs. It highlights how the Rilli quilt, handcrafted bags and baskets, and the culture of Roti and Chai are not just everyday items but embody centuries of identity, stories, and the resilience of its people.

Q2: What is Rilli and what is its significance? A2: Rilli (also spelled ralli or rilhi) is a traditional Sindhi patchwork quilt, meticulously handmade by Sindhi women using vibrant cotton fabrics, often recycled. Historically, Rilli has been a token of love and legacy, gifted at weddings, included in dowries, and used to honor guests. Each piece, stitched with intricate geometric patterns, tells a story and represents a stitched-together memory.

Q3: What role do Roti and Chai play in Sindhi culture? A3: Roti (bread) and Chai (tea) are more than just food and drink in Sindh; they are central to the culture of hospitality, community, and comfort. The shared moments over a meal reflect generosity, resilience, and simple joy. This comfort ritual, often prepared by women, is celebrated as part of Pakistan’s intangible heritage.

Q4: What types of handcrafted items are mentioned besides Rilli quilts? A4: The text mentions colorful embroidered bags and vibrant coil-woven baskets. These items are crafted by Sindhi artisans using local materials like date palm leaves, cotton threads, and recycled fabric.

Q5: Do Sindhi handcrafted bags and baskets carry symbolic meaning? A5: Yes, the patterns on these handcrafted items often carry symbolism. For example, stars can represent guidance, spirals continuity, and flowers beauty and fertility. They are seen as “portable culture,” marking the artisan’s skill and story.

Q6: What challenges do Sindhi artisans face today? A6: Sindhi artisans face significant challenges, including declining demand due to mass-manufactured goods, lack of patronage, floods, raw material shortages, and market disconnection. Many struggle to earn a living wage, and the societal value of their work remains low, despite its cultural importance.

Q7: Were Sindhi crafts historically well-known or widely traded? A7: Yes, Sindhi traditional crafts were once sold along ancient trade routes, reaching distant places like Armenia, Baghdad, Cairo, and Samarkand. Places like Hala, near Hyderabad, were historically buzzing centers of craftsmanship.

Q8: What are some other traditional Sindhi crafts besides Rilli, bags, and baskets? A8: The text mentions other traditional Sindhi crafts such as Kashi (blue tile work), Jandi (lacquered woodwork), and Ajrak and Susi (woven and dyed textiles).

Q9: What efforts are being made to preserve these fading Sindhi arts? A9: Organizations like Aik Hunar, Aik Nagar (AHAN) have stepped in to support these artisans. The text also suggests that establishing a permanent Craft Village in Karachi, similar to Dilli Haat in India, could provide a vital lifeline for preserving the craft and ensuring a thriving income model for artisans.

Q10: How can one contribute to preserving Sindhi heritage craft? A10: One can contribute by purchasing or showcasing Rilli art, and more broadly, by supporting these crafts through buying items, promoting them, or simply learning about them. This helps preserve an art form, a livelihood, and a unique way of seeing the world, preventing these traditions from becoming mere museum pieces.