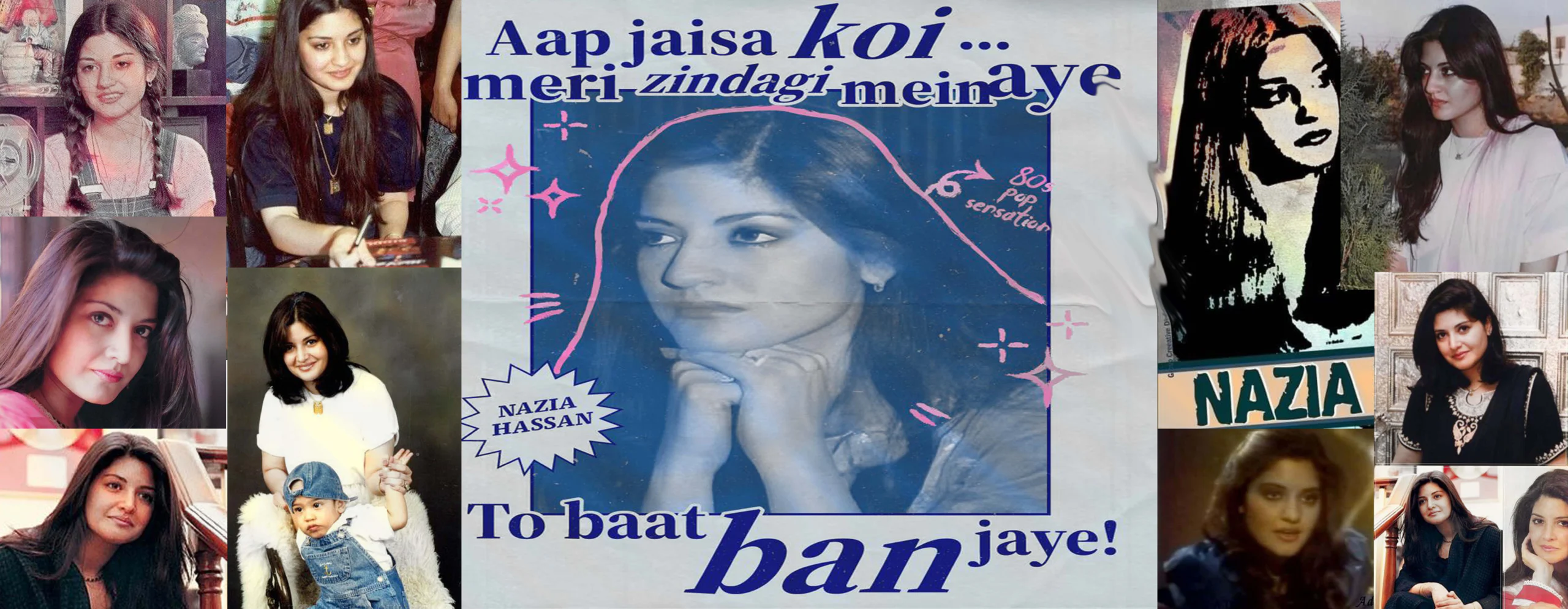

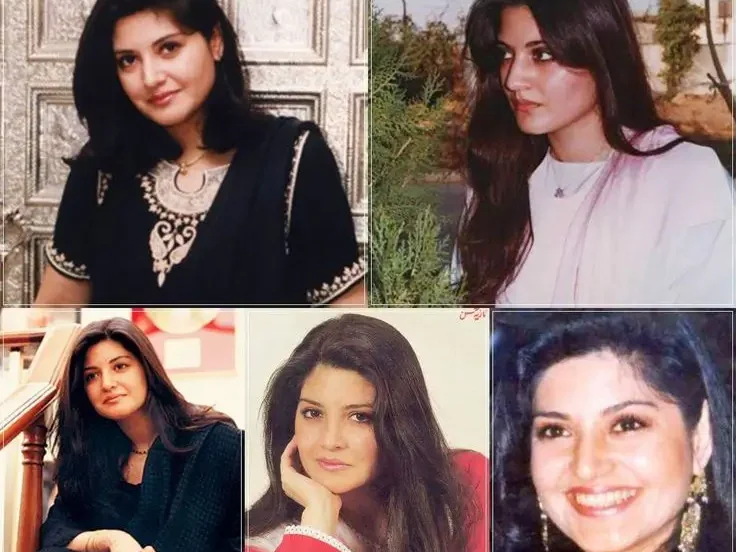

Birth, Origins, Dreams, and the Making of Nazia Hassan

Nazia Hassan was born on 3 April 1965 in Karachi, Pakistan, at a time when the country itself was still defining its post-independence cultural identity. Pakistan in the mid-1960s was negotiating modernity, tradition, and global influence simultaneously. Radio, cinema, and television were shaping public imagination, but music was still largely confined to film soundtracks and classical or semi-classical traditions.

Being born in Karachi mattered. Karachi was not only Pakistan’s largest city but also its most outward-looking metropolis. As a port city, it was culturally porous—absorbing global sounds, fashion, and ideas earlier than most of the country. This environment quietly planted the seeds for Nazia Hassan’s later ability to merge Western musical structures with South Asian emotional depth.

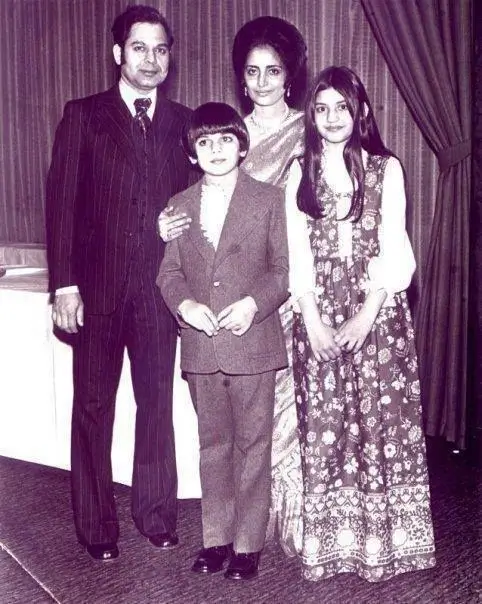

Family Roots and Values

Nazia’s father, Basir Hassan, was a disciplined businessman who believed deeply in education, self-respect, and moral grounding. He was cautious about fame and openly skeptical of the entertainment industry—especially for a young daughter. This skepticism later became a defining force, ensuring that Nazia’s artistic journey never replaced intellectual growth.

Her mother, Muniza Basir, complemented this discipline with compassion. Actively involved in social work and humanitarian causes, she instilled in Nazia Hassan a sense of empathy and civic responsibility. From her mother, Nazia Hassan learned that visibility carried obligation—that success without service was incomplete.

The household was progressive but principled. Music was encouraged, but only if it never compromised character, education, or humility.

Siblings and Emotional Ecosystem

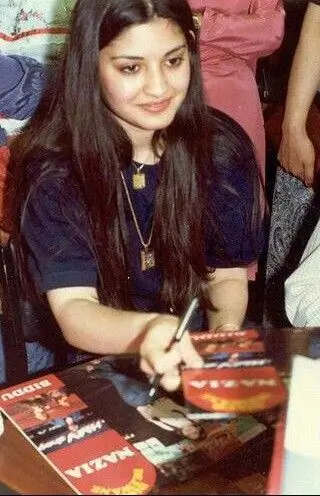

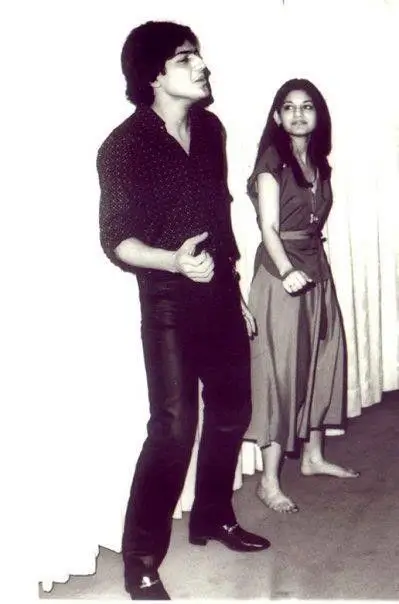

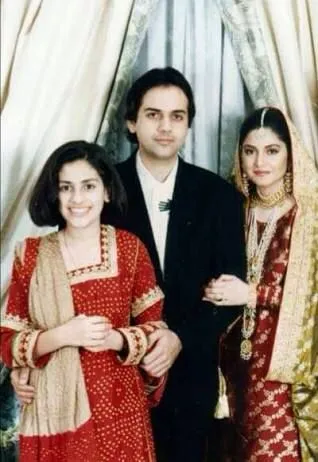

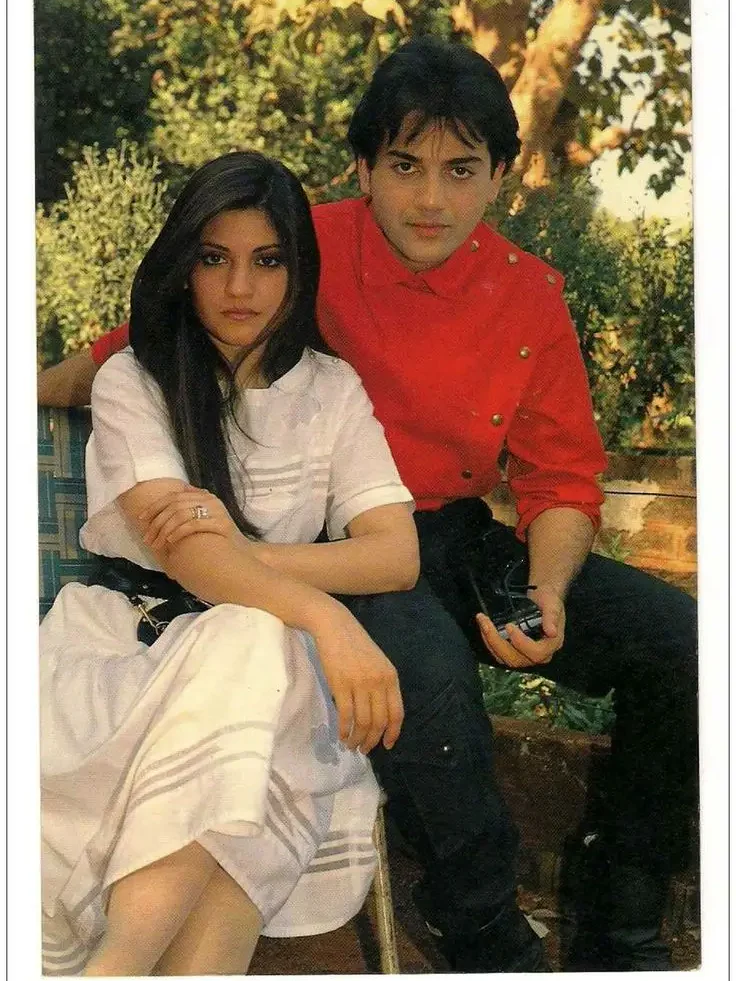

Nazia Hassan shared an exceptionally close bond with her brother Zoheb Hassan. Their relationship went beyond siblinghood—it was creative, emotional, and intellectual. Zoheb was her collaborator, sounding board, and emotional anchor.

Unlike many sibling duos shaped by rivalry, their dynamic was rooted in mutual respect. Nazia Hassan never sought dominance or individual spotlight. She believed in collective growth, a mindset that later guided their refusal of film stardom and their deliberate focus on music albums over acting careers.

Her sister Zara Hassan remained outside the limelight, reinforcing a powerful family truth: fame in the Hassan household was neither mandatory nor glorified.

Early Childhood and Personality

From early childhood, Nazia Hassan displayed a duality that would later fascinate audiences. She was shy, soft-spoken, and introspective in social settings—yet remarkably fearless in expressing ideas or performing when it mattered.

Teachers described her as inquisitive and unusually self-aware. Her questions often reflected ethical reasoning rather than surface curiosity. Even as a child, she appeared uneasy with excessive attention, a discomfort that followed her throughout life.

Her upbringing alternated between Karachi and London, exposing her to contrasting cultural rhythms. This duality became central to her identity: deeply Pakistani in values, global in expression.

Education: Discipline Before Fame

Education was never negotiable in Nazia’s life. She attended Karachi Grammar School, one of Pakistan’s most academically rigorous institutions, where she was known for her seriousness, discipline, and intellectual curiosity.

Her father’s condition—that education would never be sacrificed—was not imposed reluctantly. Nazia Hassan embraced it fully. Knowledge, to her, was independence.

Early Dreams and Inner World

Unlike many child performers, Nazia Hassan never articulated dreams of stardom. Her aspirations leaned toward impact rather than applause. Family members recall her often saying she wanted to “do something meaningful,” a phrase that revealed her inward-looking philosophy.

A defining moment came on her fourteenth birthday, when she asked that her gifts and cake be distributed among underprivileged children. This was not a symbolic act staged by adults—it was her own decision, explained simply: others needed it more.

This moment revealed an early philosophical maturity. Nazia Hassan viewed privilege as responsibility, not entitlement.

First Encounters with Music

Music entered Nazia’s life organically. She sang instinctively, without performance affectation. Her earliest television appearances on Pakistani children’s programs revealed not technical flamboyance, but emotional clarity.

On the PTV program “Kaliyon Ka Mela” in the mid-1970s, she performed “Dosti Aisa Naata.” The performance stood out not for vocal power or ornamentation, but for restraint. Even then, her voice carried sincerity rather than theatricality.

Industry observers later noted that Nazia’s strength was not volume, but truthfulness. She sang as if speaking to one person—not performing for a crowd.

Pre-Fame Ethics and Personal Code

Before her global breakthrough, Nazia Hassan already embodied traits that would later define her public image: humility, caution, and moral clarity. She resisted artificial glamour, avoided exaggeration, and remained uneasy with celebrity culture even as she reshaped it.

This discomfort was not weakness—it was restraint. She never confused applause with self-worth, nor visibility with value. Fame, to her, was a platform—not an identity.

Cultural Significance of Her Emergence

Nazia Hassan emerged not as a manufactured pop star, but as a cultural consequence of authenticity. She represented a new possibility: a Pakistani woman who could be modern without rebellion, global without erasure, and famous without moral compromise.

Her birth circumstances, family discipline, academic rigor, emotional intelligence, and early empathy formed the foundation of everything that followed.

She did not begin as a pop icon. She began as a thoughtful child navigating a complex world—and never stopped being one.

Education, Intellectual Formation, and the Mind Behind the Music

For Nazia Hassan (1965–2000), education was never a contingency plan; it was the axis around which her life revolved. Rising to international fame at just 15 with Aap Jaisa Koi (1980), she nevertheless treated learning as a stabilizing discipline rather than a distraction. At a time when celebrity could easily replace structure, she chose continuity.

Her father, Basir Hassan—a former bureaucrat and diplomat—insisted that academic life would not be interrupted by fame. Nazia Hassan accepted this not as an obligation but as a personal covenant. She did not see education and creativity as competing forces; she believed intellect sharpened expression and protected autonomy.

Schooling Across Two Worlds

Nazia’s formative education unfolded between Pakistan and the United Kingdom, giving her an unusual cognitive balance early in life. In Pakistan, she absorbed collective values, emotional literacy, and cultural sensitivity. In the UK, she encountered individualism, structured debate, and analytical rigor.

This dual exposure shaped her public voice. In interviews—whether in Karachi, London, or New York—she was neither defensive nor dismissive when questioned about culture, gender, or popular music. She answered with reason rather than reaction.

Teachers and peers consistently described her as attentive rather than loud, confident without arrogance, and serious without severity—traits that later defined her public presence.

University Years and Academic Choices

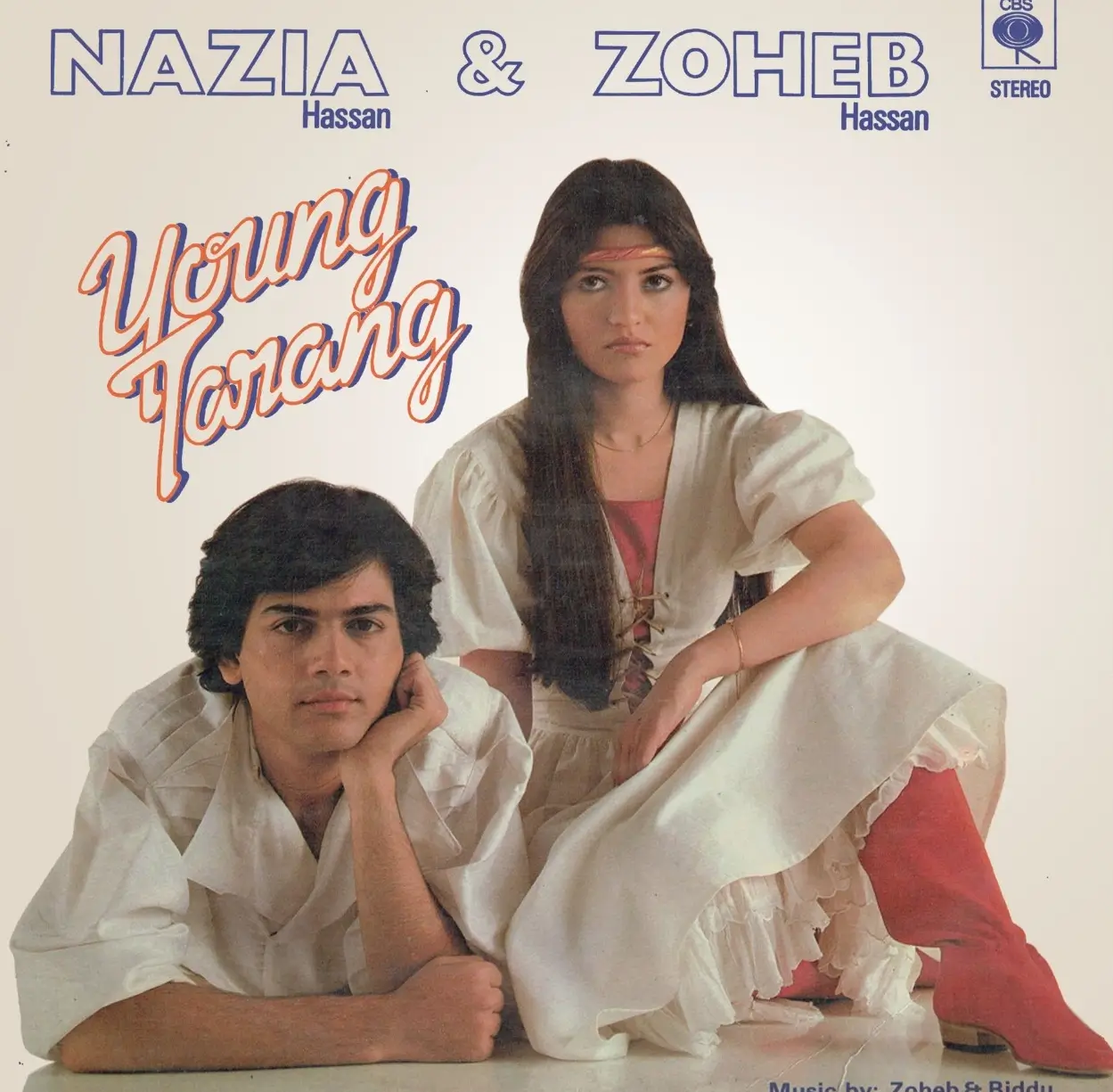

Nazia Hassan pursued higher education at Richmond, The American International University in London, earning a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration and Economics in the mid‑1980s. The choice itself was revealing. At the height of her musical success—having released albums such as Disco Deewane (1981), Boom Boom (1982), and Young Tarang (1984)—she deliberately avoided studying music or performance.

Business studies equipped her with an understanding of contracts, royalties, and the commercial mechanics of the entertainment industry—areas where many artists, particularly young women, are routinely exploited. Economics gave her a vocabulary to discuss development, inequality, and global disparity, themes she later engaged with outside music.

She subsequently completed an LLB (Bachelor of Laws) through the University of London (External Programme). Law was not a decorative credential; it reflected a growing interest in governance, rights, and international policy.

Intellectual Curiosity Beyond Credentials

Nazia’s intellectual life extended far beyond formal degrees. She read widely, followed international politics, and engaged deeply with social and humanitarian issues. Friends and collaborators recalled that she preferred conversations about world affairs, education, and policy over celebrity gossip.

She questioned power structures quietly. She did not perform outrage or chant slogans; she analyzed systems. This temperament later shaped how she navigated censorship, public criticism, and gender expectations in a conservative cultural environment.

Feminism Without Labels

Nazia Hassan never publicly branded herself as a feminist, yet her life embodied feminist principles in practice. She pursued education alongside fame, insisted on professional respect, and consistently rejected roles that reduced women to visual spectacle.

In interviews, she emphasized choice, dignity, and independence rather than confrontation. Her feminism was lived rather than advertised. She demonstrated that a woman could be modern without rejecting tradition, assertive without aggression, and successful without sacrificing ethics.

Education and Musical Judgment

Education sharpened Nazia’s musical judgment. She understood trends without being consumed by them and recognized the difference between novelty and longevity. Working closely with producer Biddu, she approached pop music with an awareness of global markets, youth culture, and technological change—while maintaining lyrical restraint.

Her academic grounding also allowed her to step away from music voluntarily. By the late 1980s, despite having sold over 60 million records worldwide with her brother Zoheb Hassan, she reduced her musical output without panic. She did not define herself solely as a singer. Music, for her, was one chapter of a larger intellectual and civic life.

Entry into International Institutions

In the early 1990s, Nazia Hassan transitioned into international public service. She became involved with United Nations–affiliated programs, including women’s leadership and development initiatives, and later worked in New York within UN-related policy environments. Her work placed her in proximity to global governance, diplomacy, and humanitarian frameworks rather than celebrity advocacy alone.

Unlike many entertainers who enter international institutions symbolically, Nazia Hassan approached this phase seriously and quietly, without media theatrics.

UNICEF and Global Responsibility

Her association with UNICEF reflected values evident since childhood: a focus on children, education, and youth development. She was particularly interested in how education could function as a long-term solution to inequality.

Colleagues noted that she attended briefings, participated in discussions, and treated her role as substantive rather than ceremonial. Fame opened the door; preparation allowed her to stay.

The Mind Behind the Voice

By the early 1990s, Nazia Hassan had become something rare: a pop icon with intellectual credibility. She could discuss music, gender norms, development policy, and global inequality with equal clarity. Her interviews were measured; she spoke slowly, chose words carefully, and avoided sensationalism.

Journalists often observed that she answered questions fully rather than performatively—an unusual trait in celebrity culture.

Quiet Authority

Nazia Hassan did not dominate conversations; she anchored them. Her authority came from coherence between belief and behavior. Education gave her vocabulary. Integrity gave her weight.

Together, they shaped a woman whose influence extended far beyond charts and awards, leaving behind a legacy of intellect, restraint, and quiet conviction.

Interviews, Cultural Philosophy, Criticism, and the Redefinition of Respectability

When Nazia Hassan entered public life in 1980, she did so in a cultural climate deeply suspicious of pop music. In Pakistan—and across much of South Asia—serious art was expected to be classical, devotional, or cinematic. Pop was widely dismissed as frivolous, Westernized, morally lax, or culturally hollow.

Nazia Hassan did not confront this hostility through rebellion or provocation. She responded intellectually and strategically. Her interviews reveal a young woman who understood that cultural change rarely occurs through confrontation; it occurs through normalization, consistency, and restraint.

Speaking Style and Media Presence

Nazia’s interview style was markedly distinct from most celebrities of her era. She spoke softly, avoided exaggeration, and resisted dramatizing her own success. Her sentences were deliberate. She listened before responding. She rarely interrupted.

Journalists frequently remarked that she treated interviews as dialogue rather than performance—a rarity in a media culture accustomed to flamboyance or defensiveness. Even critics who disliked pop music acknowledged her composure and seriousness.

She did not rely on glamour to command authority. She relied on clarity, courtesy, and self-possession.This was not accidental. It was cultural self-defense.

Defending Pop Music Without Apology

When accused of producing “non-serious” music, Nazia Hassan did not argue defensively. In interviews with publications such as Herald and international media following Disco Deewane’s success, she articulated a philosophy that reframed pop altogether.

She argued that music must reflect emotion, joy, movement, and contemporary life, not only solemnity or technical rigor. Art, she suggested, should allow people to breathe.

She compared rigid cultural gatekeeping to emotional confinement—clarifying that this was not an attack on classical traditions, but on exclusivity. Her defense of pop music was philosophical, not reactive. She framed pop as accessible art, not inferior art. This distinction mattered—and it stuck.

Cultural Confidence Without Cultural Rejection

Unlike many artists accused of “Westernization,” Nazia Hassan never positioned modernity as an escape from South Asian identity. She framed it as evolution within culture, not abandonment of it.

She wore Western clothing without provocation and respected cultural contexts without performative modesty. She sang primarily in Urdu, blended with global rhythms. She spoke fluent English but never diminished local languages or traditions. This balance made her difficult to caricature.

Critics could not easily label her rebellious, immoral, or alien. The hidden truth here is strategic: she refused the binary of tradition versus modernity—and thereby disarmed it.

Navigating Gender Expectations

As a young woman in the public eye during General Zia-ul-Haq’s Islamization era, Nazia Hassan faced scrutiny that far exceeded musical critique. Her voice, clothing, confidence, and visibility were filtered through moral standards rarely applied to male artists. Her response was neither defiance nor apology.

She refused to overexplain herself. She did not justify ambition. She did not apologize for excellence.

In interviews, she emphasized professionalism over rebellion, competence over permission. She insisted—implicitly—that women deserved respect because of capability, not compliance.

Without slogans or activism, she quietly redefined respectability for women in entertainment.

Fame at Fifteen: Discipline Over Delusion

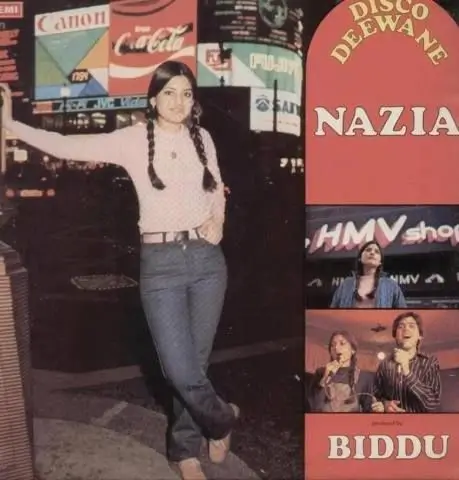

Nazia Hassan became internationally famous at fifteen, when Disco Deewane (1981) sold millions across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe—becoming one of the best-selling Asian pop albums of its time.

Despite this, her interviews reveal no trace of entitlement. She consistently credited her parents for grounding her and emphasized that education was permanent; fame was not.

She later pursued higher education in London, eventually earning a law degree, reinforcing her belief that artistic success should not replace intellectual growth.

By framing fame as conditional and transient, she avoided the psychological traps that destroy many child celebrities.

Record-Breaking Teenager: At 15, she was the first Pakistani to win a Filmfare Award (Best Female Playback Singer) and still remains the youngest recipient of the award.

Relationship with the Press

Nazia Hassan maintained a disciplined but respectful relationship with the media. She avoided scandal-driven outlets and declined to commodify her personal life.

When faced with intrusive questions, she redirected conversations calmly rather than confrontationally. She set boundaries without hostility.

This restraint earned her a reputation for dignity—even during periods of personal difficulty later in life. Her silence, often mistaken for passivity, was actually media literacy.

Censorship and Subtle Resistance

During the 1980s and early 1990s, Pakistani media functioned under strict censorship. Music videos, fashion, choreography, and lyrics were heavily monitored.

Nazia Hassan navigated this environment with tactical intelligence. She avoided overt provocation while subtly pushing boundaries through sound, imagery, and youth-centric themes.

Her album Young Tarang (1984) helped normalize the concept of music videos in Pakistan—modern in presentation but restrained in tone. It proved that visual modernity did not require vulgarity.

This quietly reshaped industry standards and created space for future artists.

Ethical Restraint and Artistic Responsibility

One of the clearest examples of Nazia’s ethical framework was her refusal to sing the song “Made in India.” Despite its commercial appeal, she declined, believing it could offend Pakistani audiences.

This decision was not framed as nationalism, but as responsibility. She recognized the symbolic weight artists carry and chose restraint over profit.

The hidden truth here is significant:

Nazia Hassan believed artistic freedom required moral consciousness, not indifference.

Public Perception at Her Peak

At her height, Nazia Hassan was perceived as youthful yet wise, glamorous yet grounded. She was aspirational without being alienating.

Young audiences admired her sound. Parents respected her discipline. Critics acknowledged her intelligence—even when skeptical of the genre itself.

She did not manufacture mystique. Her appeal rested on consistency and credibility.

Shaping Cultural Discourse

Through interviews alone, Nazia Hassan altered how pop music was discussed in Pakistan. It shifted from disposable entertainment to a legitimate expression of generational emotion.

She reframed pop not as Western imitation, but as local feeling expressed through global form. This reframing reduced resistance for future artists and laid the groundwork for Pakistan’s later pop and indie movements.

Silence as Strategy

Perhaps Nazia’s most underestimated media skill was knowing when not to speak. She did not comment on every controversy. She did not chase relevance.

Her silence was not absence—it was control. By refusing overexposure, she protected her credibility and inner life.

The Intellectual Pop Star

By the early 1990s, Nazia Hassan had become a rare figure in South Asia:

an intellectual pop star in a region that rarely allowed such synthesis.

She proved that popularity and thoughtfulness were not opposites. Her interviews remain relevant not because of nostalgia, but because of coherence. She said what she believed—and lived accordingly.

That consistency is the hidden truth behind her enduring respect.

Nazia Hassan’s Musical Legacy

Before examining individual songs, it is essential to understand what made Nazia Hassan (1965–2000) musically distinct. Her voice was light, youthful, and technically unforced, yet emotionally precise. She did not overpower compositions; she inhabited them. Her singing carried innocence without naïveté and confidence without aggression—an extremely rare balance in South Asian popular music.

Musically, her work fused Western disco, synth-pop, funk, and dance structures—largely composed and produced by Biddu—with South Asian melodic phrasing and Urdu lyricism. Lyrically, her songs focused on youth, longing, joy, uncertainty, emotional honesty, and everyday feeling rather than cinematic melodrama or tragic excess.

Her music was modern without being disposable. This is why it endured.

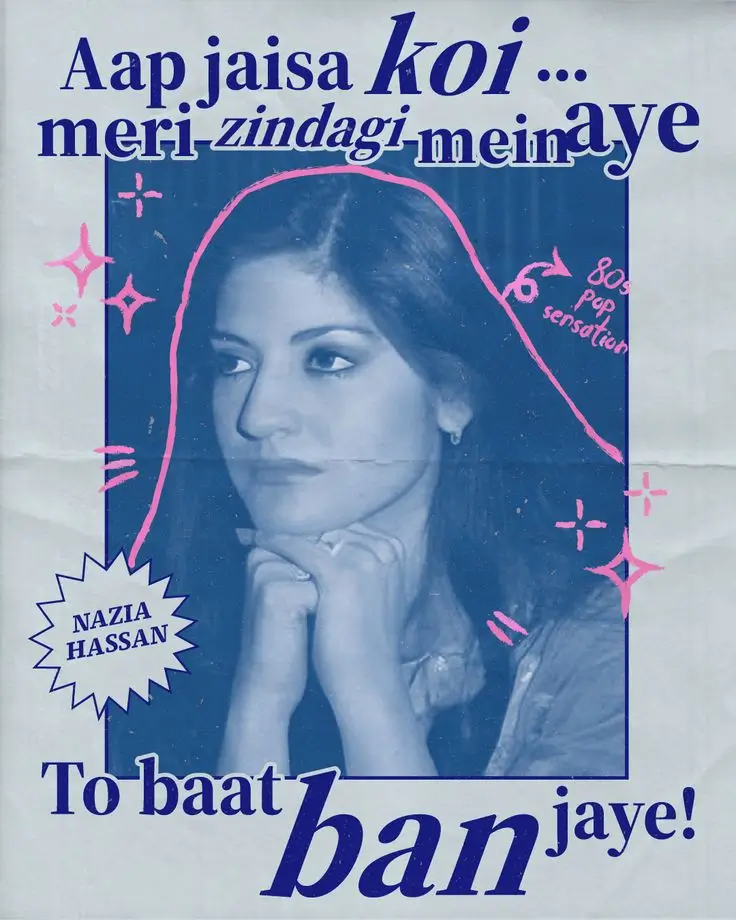

1) Aap Jaisa Koi (1980)

Originally recorded for the Bollywood film Qurbani (1980), Aap Jaisa Koi changed the musical direction of the subcontinent almost overnight.

Structurally rooted in disco, its emotional impact came from contrast. Nazia’s restrained, almost conversational delivery softened the bold rhythm, creating intimacy instead of spectacle.

Lyrically, the song expressed desire without desperation. It spoke of admiration rather than conquest—an emotional posture rarely given to female voices in mainstream cinema at the time.

The unspoken truth:

This song introduced a female subjectivity that was neither submissive nor theatrical. It gave young listeners permission to feel quietly, without excess.

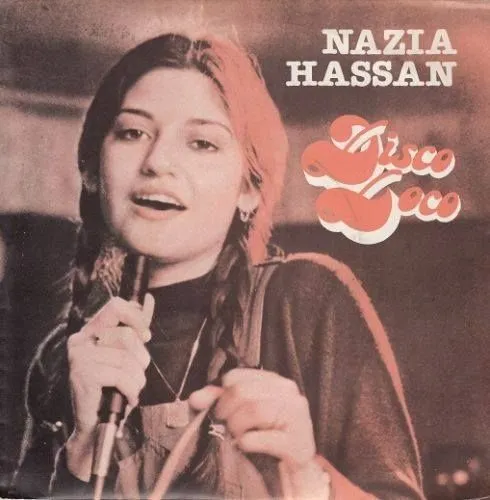

2) Disco Deewane (1981)

The title track of her debut album Disco Deewane became a generational anthem across Pakistan, India, the Middle East, Europe, and parts of Africa. The album sold millions of copies worldwide, making it one of the most successful Asian pop albums of its era.

On the surface, the song celebrated joy, movement, and collective energy. Beneath that surface lay a cultural rupture.

Disco Deewane normalized the use of English phrases within South Asian pop without alienating local audiences. Nazia’s pronunciation and tone made global language feel accessible rather than elitist.

Hidden truth:

The song proved South Asian pop could be exported intact, not diluted for Western consumption.

3) Boom Boom (1982)

Boom Boom leaned unapologetically into dance music. It was rhythmic, playful, and international in sound—later adapted into multiple languages and even reworked in global pop contexts.

Yet Nazia’s restraint prevented the song from becoming aggressive. She left space between lines, allowing rhythm to breathe.

This demonstrated her intuitive understanding of pacing and silence, a quality missing in many louder contemporaries.

The song became especially significant among diaspora youth, who used it as a bridge between cultural memory and modern identity.

4) Dum Dum Dede (1982)

This track revealed Nazia’s experimental edge. With its whimsical, almost nonsensical phrasing, the song drew from fantasy and childhood imagination rather than narrative storytelling.

Instead of meaning, it offered mood.

Its longevity—and its reuse in cinema decades later—confirms its atmospheric power. Listeners continue to project their own emotions onto it.

Unspoken truth:

This song quietly challenged the assumption that pop must explain itself to be valid.

5) Ankhen Milane Wale (1982)

This song explored romantic tension through anticipation rather than fulfillment. Nazia’s voice conveyed hesitation, curiosity, and emotional vulnerability.

Musically restrained, the arrangement allowed emotional nuance to guide the melody.

It resonated deeply with young listeners experiencing first attraction—especially young women rarely given such emotional realism in pop narratives.

6) Dil Ki Lagi (1984)

Dil Ki Lagi carried emotional depth without tragedy. It treated attachment as experience, not suffering.

Nazia Hassan sang with acceptance rather than despair, offering a maturity beyond her age. This was radical in a cultural context that often framed female emotion as either sacrificial or catastrophic.

Hidden truth:

The song normalized emotional self-awareness rather than emotional punishment.

7) Dosti (1984)

Dosti was unusual in centering friendship as a primary emotional bond—especially in a genre dominated by romance.

Its sincerity made it relatable across generations and reinforced Nazia’s image as emotionally grounded and socially conscious.

Friendship, in her music, was not secondary.

It was foundational.

8) Aa Haan (1984)

This track leaned into flirtation and playful confidence. Yet even here, Nazia Hassan avoided exaggeration.

She suggested joy rather than performing it.

The song expanded the emotional range available to female pop singers—showing that women could be playful without being trivialized.

This contributed subtly but significantly to the normalization of female agency and pleasure in pop music.

9) Camera Camera (1992)

Her final album marked a tonal and philosophical shift. Camera Camera was associated with anti-drug awareness and social responsibility, particularly among youth.

The sound matured alongside her worldview. The themes became reflective rather than celebratory.

This album was not a decline—it was closure.

Hidden truth:

Nazia Hassan exited pop at her peak rather than being consumed by it.

Collaborative Dynamics with Zoheb Hassan

Zoheb Hassan was not merely a supporting voice. His grounded, rhythmic tone contrasted with Nazia’s airy emotionality.

Together, they formed a balanced musical dialogue, not a hierarchy. Their sibling collaboration modeled emotional equality rather than dominance.

This dynamic influenced later group and duo formations in South Asian pop.

Musical Restraint as Power

Nazia’s greatest strength was restraint. She did not rely on vocal acrobatics or excess emotion.

She trusted tone, timing, and silence. This restraint is why her music aged gracefully. It does not feel trapped in the 1980s. Her songs are rediscovered not because of nostalgia—but because they still breathe.

Influence on Future Artists

Across decades, artists in Pakistan, India, and the diaspora have cited Nazia Hassan as foundational.

She expanded what was permissible in sound, image, language, and emotional expression. Without her, later pop movements would have faced greater resistance, slower acceptance, and narrower possibility. Her influence is structural, not stylistic.

Why Her Music Still Aligns Today

Nazia Hassan’s music aligns with contemporary sensibilities because it was emotionally honest rather than trend-driven. She sang about feeling, not fashion.

In an era obsessed with reinvention, her authenticity remains rare. Her voice still sounds like possibility—not performance.

Personal Struggles, Marriage, Withdrawal from Music, and the Cost of Visibility

Nazia Hassan’s public life began before her private self had the chance to fully form. At fifteen, she became an international star—celebrated across Pakistan, India, the Middle East, and Europe—at an age when identity is still fragile.

The acclaim was genuine, but it was also consuming. Every lyric, appearance, and personal choice became open to interpretation and judgment. In a conservative society, visibility itself became a form of exposure, especially for a young woman whose success was unprecedented.

The unspoken truth is structural:

Nazia Hassan did not simply become famous early—she became symbolically burdened early, forced to carry debates about morality, modernity, and gender far beyond her age.

Conservatism, Backlash, and Gendered Moral Policing

As her popularity expanded through the 1980s, resistance intensified. Conservative religious voices and cultural commentators criticized her music, image, and public presence as Westernized and morally disruptive.

There were documented instances of public denunciations, campaigns against pop music, and threats, particularly during the Zia-era climate where cultural expression was heavily moralized. While the language of “fatwas” and effigy-burning circulated widely in public discourse and media reporting, what is historically certain is that she became a lightning rod in a broader ideological conflict.

Crucially, the criticism was rarely musical. It was moral, gendered, and symbolic.

Nazia’s very existence as a confident, visible Pakistani woman was framed as transgression. She did not respond with apology or provocation. She simply continued—until continuing itself became too costly.

Choosing Education Over Industry Dependence

Unlike many child stars, Nazia Hassan refused to let fame define her future. Even at the height of her success, she prioritized education.

She studied in London, completing coursework in economics and business administration, and later pursued law through the University of London’s external programme, eventually qualifying as a barrister (LLB).

This decision was not a retreat from music—it was a declaration of autonomy. Education became her exit strategy, her insurance against being permanently consumed by celebrity.

Hidden truth:

She understood early that artistic success does not guarantee personal power, especially for women.

Intentional Withdrawal from Music

By the early 1990s, Nazia’s public presence began to recede. This was not due to declining relevance. Her albums still sold. Her influence remained intact.

But she reduced performances, declined commercial offers, and avoided the machinery of aggressive promotion. Camera Camera (1992) received limited publicity by choice, not neglect.

Her withdrawal was widely misread as fading stardom. In reality, it was strategic self-preservation. She was stepping away before the industry could hollow her out.

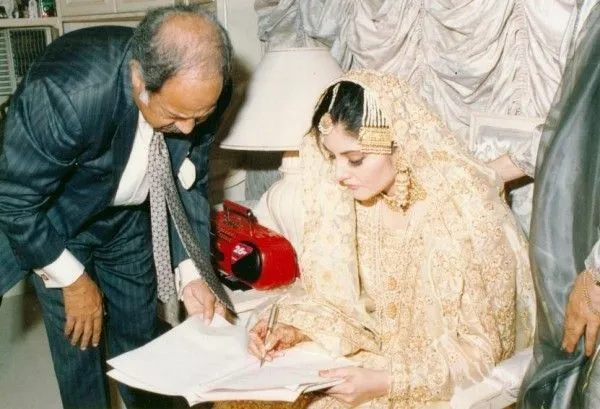

Marriage and the Illusion of Stability

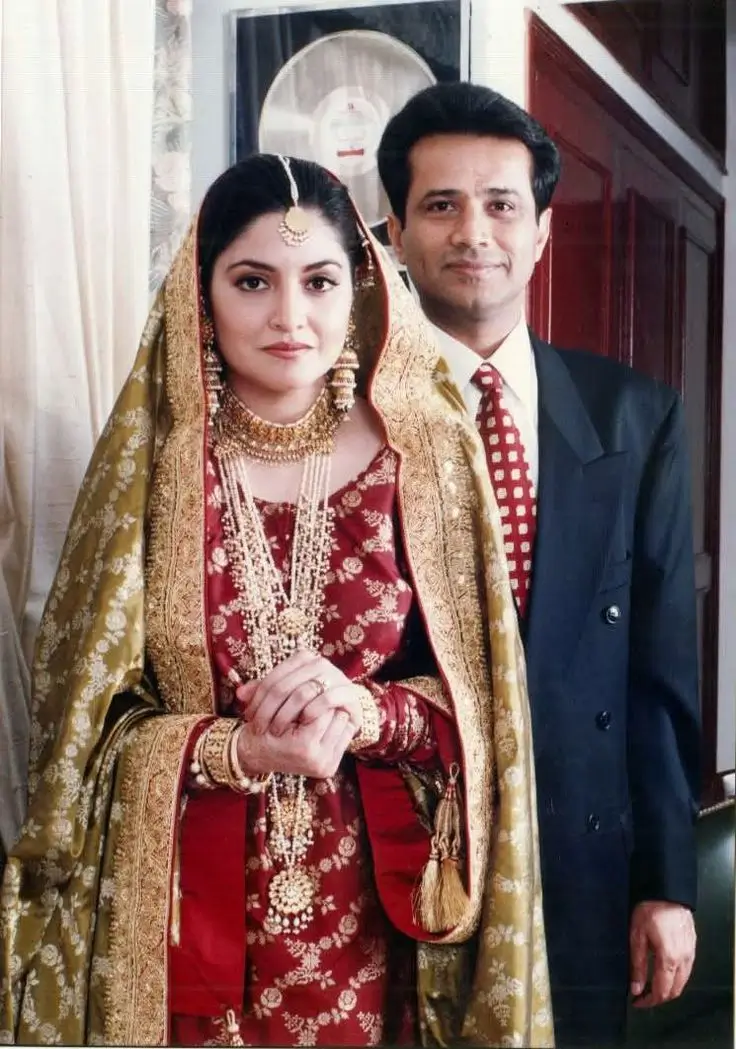

In 1995, Nazia Hassan married Mirza Ishtiaq Baig, a banker. Public narratives framed the marriage as a settling of life—a transition into domestic stability.

Privately, it marked the beginning of her most painful chapter.

Court documents, affidavits, and later testimony revealed a relationship marked by emotional neglect, financial control, and physical abuse. For a woman known publicly for independence and dignity, this contradiction was devastating.

The unspoken truth here is brutal:

Public empowerment does not immunize women from private violence.

Silence as Survival, Not Submission

For years, Nazia Hassan remained publicly silent about her marriage. This silence has often been misread as passivity.

In reality, it reflected cultural constraint and survival calculus. Divorce carried heavy stigma. Public disclosure risked reputational harm, custody battles, and social isolation.

Her silence was not weakness. It was endurance under constraint.

She continued charitable work, motherhood, and public composure while enduring private suffering invisible to fans.

Motherhood as Emotional Anchorage

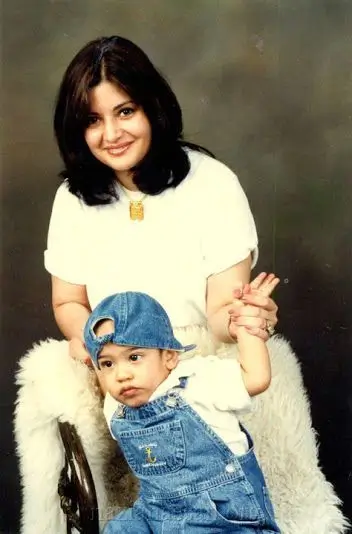

The birth of Nazia Hassan son became her stabilizing force. Nazia Hassan repeatedly described motherhood as her greatest source of meaning and strength.

Her priorities shifted decisively. Career ambition yielded to protection, care, and responsibility. Motherhood did not diminish her identity—it deepened it, anchoring her during instability.

Illness and Compounding Vulnerability

In 1998, Nazia Hassan was diagnosed with lung cancer, a shocking diagnosis for a lifelong non-smoker in her early thirties.

Treatment in London was physically exhausting and emotionally isolating. As her marriage deteriorated, her health crisis exposed the fragile scaffolding beneath her public success.

Illness stripped away remaining illusions of control and amplified existing power imbalances.

The hidden truth here is intersectional:

Gender, illness, and dependence collided at her most vulnerable moment.

Breaking Silence Through Law

Toward the end of her life, Nazia chose to speak—not through media, but through legal testimony. She accused her husband of abuse, abandonment, and refusal to provide financial support for medical treatment.

This was an act of extraordinary courage in a culture where women are often pressured to endure silently.

Her voice, once musical, became testimonial. She reclaimed narrative through law when culture denied her speech.

Divorce as Reclaimed Agency

The marriage ended shortly before her death in August 2000. Though brief, the separation represented restored agency.

Divorce did not erase suffering—but it restored dignity.

For countless women, especially in South Asia, her decision became quietly transformative: a reminder that self-respect can outweigh social approval.

Media Reduction and Narrative Injustice

Posthumous media narratives often reduced Nazia’s final years to tragedy—illness, abuse, decline. This framing erased her resilience, intellect, legal training, activism, and moral clarity.

She was not a fallen star. She was a woman navigating layered oppression with coherence and courage.

The Psychological Weight of Iconhood

Iconhood offered Nazia Hassan visibility but denied her vulnerability. She carried expectations that allowed no room for failure, fear, or collapse.

Her withdrawal from music was not abandonment. It was boundary-setting. She refused to let public demand devour her private self.

Reclaiming Selfhood Beyond Music

In her final years, Nazia Hassan was not defined by stardom. She was a lawyer, mother, activist, and survivor.

Music introduced her to the world. Strength carried her through it. Her silence during this period was not absence. It was transition.

International Representation, Global Impact, and Breaking Barriers

Though Nazia Hassan (1965–2000) never held an official government position, she became one of Pakistan’s most effective unofficial cultural ambassadors. Through her music, interviews, and international collaborations, she represented a modern, articulate, and globally conversant Pakistan at a time when the country’s image abroad was largely filtered through geopolitics, conflict, or religious conservatism.

From India to the United Kingdom, across the Middle East, Europe, and parts of Africa, her presence became synonymous with a new Pakistani cultural identity—urban, youthful, confident, and emotionally expressive.

For many international listeners, Nazia Hassan was their first encounter with Pakistani popular music beyond classical ghazals or qawwali traditions.

Breaking Geographical and Cultural Barriers

Central to Nazia’s global reach was her collaboration with Biddu (Biddu Appaiah), the Indian-born, UK-based producer who had already achieved international success with Western disco hits in the 1970s.

Songs like Aap Jaisa Koi (1980) and Disco Deewane (1981) combined Urdu lyrics, South Asian melodic sensibility, and Western disco-pop production, creating music that crossed linguistic and cultural borders without translation.

The unspoken truth here is strategic:

Nazia’s music did not chase Western validation—it met global audiences on equal footing, proving that Pakistani pop could be as polished, catchy, and contemporary as any Western or Indian production.

International Reach and Media Presence

By the early 1980s, Nazia’s songs were:

- played on international radio stations,

- aired on foreign television networks, and

- circulated widely through cassette culture across the Middle East, Europe, and South Asia.

Disco Deewane reportedly sold millions of copies worldwide, an extraordinary figure for a South Asian pop album at the time. The album topped charts in several countries and remained in circulation for years, particularly among diaspora communities.

This was not accidental success. It was transnational cultural penetration at a time when Pakistani artists had little access to global distribution networks.

Awards and Recognition Abroad

Nazia Hassan received recognition across borders, most notably becoming the first Pakistani artist to win the Filmfare Award (Best Female Playback Singer for Aap Jaisa Koi in 1981)—a historic moment that symbolically bridged Pakistan and India during a period of political tension.

She was also acknowledged in the UK and Europe through music industry platforms that celebrated her role in introducing South Asian pop to wider audiences.

International critics noted her clarity of voice, emotional restraint, and natural charisma, marking her as a crossover artist who did not dilute cultural identity for mass appeal.

Hidden truth:

Her recognition abroad often preceded full acceptance at home—an inversion common for artists who challenge domestic norms.

Influence on Global and Regional Pop Culture

Nazia’s aesthetic—musical and visual—proved influential well beyond her immediate career. The blending of Eastern melodies with Western instrumentation, the use of dance-centric rhythms, and her understated performance style informed later generations of singers in Pakistan and India.

Bollywood playback, Pakistani pop in the 1990s, and even diaspora pop acts echoed elements of her approach.

Her visibility also exposed a contradiction within Pakistan:

a nation proud of global success yet uneasy about modern female visibility.

Nazia Hassan navigated this tension with composure, refusing to become either defiant or apologetic.

Media Presence and Intellectual Ambassadorship

Nazia’s international interviews consistently revealed intelligence, humor, and self-awareness. She spoke openly about:

- the pressures of fame,

- the importance of education,

- women’s autonomy, and

- cultural dignity in art.

She repeatedly emphasized that music should uplift rather than degrade, and that modernity need not erase cultural values.

Through this, she functioned less like a celebrity and more like an informal cultural envoy, articulating Pakistan’s complexity rather than simplifying it for foreign audiences.

Cross-Border Acceptance Amid Political Tension

During periods of strained India–Pakistan relations, Nazia’s music circulated freely across borders—often unofficially, but enthusiastically.

Songs like Disco Deewane and Boom Boom became Indian hits despite political restrictions, demonstrating that popular culture often travels where diplomacy fails.

She became a symbol of shared South Asian emotional vocabulary, showing that rhythm, longing, and joy could transcend national divides.

This paved the way—symbolically and practically—for later Pakistani artists seeking cross-border recognition.

Influence on Female Pop Artists

Female singers across South Asia have repeatedly cited Nazia Hassan as a formative influence. Her career demonstrated that women could:

- dominate pop charts,

- command global audiences, and

- retain intellectual and personal dignity.

She normalized the idea that a young South Asian woman could be ambitious, educated, and globally successful without cultural erasure.

The hidden truth:

She expanded not just musical possibility—but gendered possibility.

Charity, Humanitarian Work, and Social Advocacy

Beyond music, Nazia Hassan was quietly committed to philanthropy. She believed fame was a responsibility, not a reward.

Her focus areas included:

- education,

- women’s welfare, and

- healthcare access.

She supported causes both in Pakistan and abroad, often without publicity.

Education and Youth Advocacy

Education was central to Nazia’s worldview. She advocated strongly for girls’ education, linking learning to independence and social mobility.

She supported educational initiatives, participated in seminars, and used interviews to urge investment in schools, literacy programs, and youth mentorship.

Her own academic pursuits reinforced the credibility of this advocacy.

Health, Women’s Welfare, and Domestic Violence Awareness

Nazia Hassan contributed to healthcare initiatives, particularly those addressing women’s and maternal health. She supported awareness around nutrition, vaccination, and preventive care.

She also lent her voice to campaigns against domestic violence, challenging cultural silence around abuse—an issue that would later intersect tragically with her own life

Support for Orphans and Vulnerable Children

She supported orphanages and children’s shelters, believing that stable environments could interrupt cycles of neglect and poverty.

Her work often involved collaboration with NGOs, reflecting her global yet locally grounded sense of responsibility.

Music as a Platform for Awareness

Even during her musical career, Nazia Hassan participated in benefit concerts, public service messaging, and socially conscious initiatives.

After withdrawing from music, her influence continued through causes she endorsed and inspired.

Championing Women in the Arts

Nazia Hassan actively encouraged women pursuing careers in music, media, and the arts. She mentored informally, reassured young artists that ambition and cultural authenticity could coexist, and modeled a path that did not require self-erasure.

Many later female Pakistani artists cite her—directly or indirectly—as proof that such a path was possible.

Lasting Impact and the Hidden Truth of Soft Power

Nazia Hassan’s philanthropy and global representation were not side notes to her career—they were extensions of her ethical framework.

Her music immortalized her publicly. Her values immortalized her privately.

The hidden truth is this:

Long before “soft power” became a policy term, Nazia Hassan embodied it—using culture, empathy, and restraint to project a nation more truthfully than slogans ever could.

She showed that artistry and humanitarianism were not opposites—but partners.

Marriage, Family Life, Later Works, and Albums

Nazia Hassan married Mirza Ishtiaq Baig on March 30, 1995, in Karachi. The marriage was arranged, reflecting the cultural norms of her social milieu—particularly for women from respected families, regardless of global fame.

Publicly, the union appeared conventional and respectable. Privately, it proved deeply troubled.

In later legal proceedings and public statements toward the end of her life, Nazia alleged emotional abuse, neglect, and financial control, including refusal to support her medical treatment. These revelations shocked many precisely because they contradicted the polished image of domestic stability often imposed on successful women.

Unspoken truth:

In South Asian societies, marriage is often presented as a corrective to female independence. For Nazia, it became a site where public empowerment collided with private vulnerability.

Despite this, she did not abandon her principles. Even while enduring personal distress, she continued to speak—carefully but clearly—about women’s dignity, autonomy, and the right to safety within marriage.

Motherhood: Emotional Grounding Amid Turmoil

On April 7, 1997, Nazia gave birth to her son, Arez. Motherhood marked a profound emotional shift.

Those close to her recall that her son became her emotional anchor. She spoke of motherhood as both joy and responsibility—a commitment that reoriented her priorities toward protection, stability, and long-term meaning.

In interviews, she highlighted the importance of nurturing children with compassion and values, revealing a softer but no less determined dimension of her personality.

Hidden truth:

Motherhood gave Nazia not retreat from the world—but a reason to endure it.

Musical Career: Maturity, Experimentation, and Conscious Withdrawal

Later Music and Artistic Evolution

After her explosive success in the early 1980s with Disco Deewane (1981), Boom Boom / Star (1982), and Young Tarang (1983), Nazia continued recording with her brother Zoheb Hassan and producer Biddu.

Her fourth album, Hotline (1987), reflected artistic maturity. The lyrics were more reflective, the compositions more experimental, blending Western pop structures with South Asian sensibility and emerging social consciousness.

Her final solo album, Camera Camera (1992), marked a clear thematic shift. Though less commercially promoted, it addressed issues such as drug abuse and youth responsibility, demonstrating that she viewed pop music as a medium for awareness, not just entertainment.

This was not decline—it was intentional evolution.

Collaborative Dynamics

The Nazia–Zoheb–Biddu collaboration defined an era of South Asian pop. Their work fused disco, synth-pop, and dance music with Urdu lyrics and regional melodic phrasing—years ahead of mainstream acceptance.

Nazia insisted on authenticity and creative freedom, resisting formulas that reduced pop to imitation. Her role was not passive; she shaped tone, delivery, and emotional direction

Notable Albums (Chronologically Anchored)

- Disco Deewane (1981) – Breakthrough album; charted in multiple countries

- Boom Boom / Star (1982) – Included Bollywood film tracks

- Young Tarang (1983) – Introduced modern music videos in Pakistan

- Hotline (1987) – Mature themes, sonic experimentation

- Camera Camera (1992) – Socially conscious, final solo album

Semi-Retirement and Reclaiming Privacy

By the early 1990s, Nazia began stepping back from active music production. This was not forced by irrelevance but chosen for self-preservation.

She reduced public appearances, declined offers, and focused on education, family, and philanthropy. Interviews became selective. Privacy became essential.

Unspoken truth:

For women icons, withdrawal is often misread as fading. For Nazia, it was boundary-setting.

Illness: Vulnerability Without Spectacle

In the late 1990s, Nazia was diagnosed with lung cancer, an especially shocking diagnosis given her age and non-smoking lifestyle.

She underwent treatment in London, largely away from public view. Even during illness, she continued to manage family responsibilities and remained involved—quietly—in charitable causes.

Friends recall her composure, discipline, and refusal to let illness define her identity.

Hidden truth:

She chose dignity over dramatization in a world that often demands spectacle from women’s suffering.

Nazia Hassan Death and Family Aftermath

Nazia Hassan passed away on August 13, 2000, in London, at the age of 35.

Her death triggered an outpouring of grief across Pakistan, India, and the global South Asian diaspora. Tributes came from musicians, journalists, and fans who recognized her as a cultural pioneer.

For her family, grief was deeply private. Her brother Zoheb Hassan has since spoken sparingly, choosing to honor her legacy through music rather than public commentary. Her son Arez has been raised away from the spotlight, reflecting the family’s decision to protect his privacy.

Unspoken truth:

After years of public ownership of her image, her family reclaimed silence as an act of love.

Legacy: Music, Meaning, and Memory

Nazia Hassan’s legacy endures across generations. Songs like Disco Deewane, Aap Jaisa Koi, and Boom Boom remain cultural touchstones—sampled, remixed, and rediscovered.

She is widely credited with:

- pioneering pop music in Pakistan,

- normalizing music videos,

- opening global pathways for South Asian artists, and

- redefining female presence in popular culture.

Cultural Representation and Soft Power

Through international tours, interviews, and releases, Nazia functioned as an unofficial cultural ambassador. She challenged stereotypes of Pakistan by embodying modernity, intellect, and emotional openness.

She demonstrated that cultural confidence need not be loud—and that representation can be ethical.

Charity and Social Commitment

Even within a short life, Nazia engaged in:

- advocacy for education,

- support for cancer awareness, and

- fundraising for disaster relief.

Her philanthropy was understated but consistent, reflecting her belief that fame should translate into responsibility.

Final Reflection: The Unspoken Truth

Nazia Hassan’s life cannot be reduced to tragedy, nor to triumph alone.

Her story reveals a deeper truth:

that visibility comes at a cost for women who challenge norms,

that silence can be strategy,

and that dignity is sometimes preserved by stepping away.

Her music introduced joy to millions.

Her life teaches resilience without bitterness.

And that may be her most enduring legacy.

Nazia Hassan: Achievements and Awards

Historic Achievements

1. First Pakistani to Win a Filmfare Award (India)

- Award: Filmfare Award for Best Female Playback Singer

- Year: 1981

- Song: Aap Jaisa Koi (Film: Qurbani, 1980)

This was a landmark moment in South Asian cultural history. Nazia became:

- the youngest recipient of a Filmfare Award at the time, and

- the first Pakistani artist—male or female—to receive this honor in India.

Unspoken truth:

At a time of strained India–Pakistan relations, this award quietly demonstrated how culture could succeed where politics failed

2. Pioneer of Pop Music in Pakistan

Nazia Hassan is universally credited as the founder of modern pop music in Pakistan.

Before her:

- Pakistani popular music was largely limited to film playback, ghazals, qawwali, and classical genres.

After her:

- pop music became a legitimate, mainstream genre.

Her debut album Disco Deewane (1981) redefined what Pakistani music could be—global, youth-driven, and contemporary

3. International Commercial Success

- Disco Deewane charted in multiple countries across Asia, the Middle East, and Europe.

- The album sold millions of copies worldwide, making it one of the most successful South Asian pop albums of its era.

She achieved international success without relocating permanently to the West, an uncommon feat for South Asian artists at the time.

4. First Pakistani Artist with Global Pop Identity

Nazia was:

- played on international radio,

- featured on foreign television, and

- embraced by South Asian diaspora communities worldwide.

For many global listeners, she was their first exposure to Pakistani pop music.

5. Introduction of Music Videos in Pakistan

Her album Young Tarang (1983) featured what are widely regarded as the first modern Pakistani pop music videos.

This transformed:

- how music was promoted, and

- how artists visually represented themselves.

She set the template later used by Pakistani pop and rock artists in the 1990s.

6. Cross-Border Cultural Impact

Despite political restrictions:

- her music was widely consumed in India,

- remixed and replayed across borders, and

- embraced by both Pakistani and Indian audiences.

This paved the way for later Pakistani artists seeking regional acceptance.

Confirmed Awards and Honors

Filmfare Award (India)

- Best Female Playback Singer – Aap Jaisa Koi (1981)

Multiple Gold and Platinum Certifications

- For albums including Disco Deewane and Boom Boom / Star

(Exact certification standards varied by country, but sales milestones were widely reported in contemporary media.)

International Recognition

- Honored at music events and cultural platforms in the UK, Middle East, and Europe for her role in introducing South Asian pop to global audiences.

Posthumous Honors

Pride of Performance Award (Pakistan)

- Year: 2002 (posthumous)

- Conferred by: Government of Pakistan

This is Pakistan’s highest civilian award in arts and culture, recognizing her foundational role in music and cultural representation.

Unspoken truth:

The award came after Nazia Hassan death—reflecting a familiar pattern where women pioneers are fully acknowledged only once they are no longer disruptive.

Cultural and Academic Recognition

Though not always formalized as awards, Nazia Hassan has been:

- included in music history curricula,

- cited in gender and media studies, and

- referenced in cultural diplomacy research as an example of soft power.

Her life and work are frequently discussed in:

- documentaries,

- retrospectives, and

- academic writing on South Asian pop culture.

Legacy Achievements (Beyond Trophies)

- Opened global pathways for Pakistani artists

- Redefined female respectability in pop culture

- Normalized Western–Eastern musical fusion

- Created a sustainable pop template later used by the Pakistani music revival of the 1990s

- Remains one of the most sampled, covered, and referenced South Asian pop artists decades after Nazia Hassan death

The Unspoken Achievement

Perhaps Nazia Hassan’s greatest achievement was never inscribed on a plaque:

She proved that a Pakistani woman could be

globally successful, intellectually grounded, culturally rooted, and morally autonomous—

without asking permission.

That legacy endures beyond awards.

Nazia Hassan Songs – Iconic & Well‑Known

Songs From Young Tarang & Other Albums

- Aap Jaisa Koi

- Disco Deewane

- Dreamer Deewane

- Aao Na (also listed as Aao Naa / Aao Naa Pyar Karen)

- Tere Kadmon Ko

- Boom Boom

- Aankhein Milane Wale

- Dosti

- Dum Dee Dee Dum

- Aag

- Sunn

- Chehra

- Ashanti

- Kya Hua

Songs From Hotline & Later Singles

- Telephone Pyar

- Teri Yaad

- Khubsoorat

- Dheeray Dheeray

Songs From Camera Camera (1992)

- Camera

- If

- Mehrbani

- Wala Wai

- Tali de Thullay

- Camera (Dance Mix)

- Nasha

- Pyar Ka Geet

- If You Could Read My Mind

- Mama Papa

- Dil Ki Lagi

- Kyoun

Film & Other Tracks

- Main Aaya Tere Liye (from Ilzaam)

- Aap Ka Shukriya

- Raat Ke Dukhiya Saaye

- Dhundhli Raat

- No Entry (duet with Kishore Kumar)

- Rock n Roll (duet with Kishore Kumar & Bappi Lahiri)

Other Songs Often Included in Collections

- Hamesha

- Tum Aur Hum

- Pyar Ka Jadoo

- Ooee Ooee

- Koi Nahin

- Muskurae Ja

This list includes studio recordings, film soundtracks, and notable tracks from compilation and remix releases associated with her career, spanning from her debut in 1980 through her last album era.

Final Overview

Nazia Hassan’s life was a blend of talent, ambition, and cultural impact. She broke barriers for female artists in Pakistan, pioneered pop music in South Asia, and left a legacy that continues to resonate decades after her passing. Her music, charity work, and international presence made her a beloved figure not just in Pakistan but across the globe.

Nazia’s story reflects courage, creativity, and the enduring power of art to transcend time. From her early dreams in Karachi to international stages, her journey symbolizes the evolution of Pakistani pop music and the potential of cultural diplomacy through art.

Even today, young musicians and fans revisit her songs, celebrating the timeless melodies and messages she left behind, ensuring that Nazia Hassan’s influence remains alive and vibrant.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who was Nazia Hassan?

Nazia Hassan was a Pakistani pop singer, composer, and cultural icon. She gained fame in the 1980s with hits like Disco Deewane and Aap Jaisa Koi.

Where was Nazia Hassan born?

She was born in Karachi, Pakistan, on April 3, 1965.

What were her early dreams?

Nazia aspired to become a singer and inspire young women in Pakistan through music and performance.

What were her major achievements?

She became the first Pakistani singer to gain international recognition, won multiple awards, and pioneered pop music in South Asia.

Which albums did she release?

Some notable albums include Disco Deewane, Boom Boom, Young Tarang, Hotline, and Camera Camera, often in collaboration with her brother Zoheb Hassan.

Did Nazia Hassan represent Pakistan internationally?

Yes, she performed globally, participated in international music events, and represented Pakistani talent on a worldwide stage.

What charity work did she do?

She supported education for underprivileged children, cancer awareness campaigns, and disaster relief initiatives.

Who are her family members?

Her brother Zoheb Hassan is a musician, and her son Arez continues her legacy privately. Extended family members occasionally honor her memory publicly.

How did Nazia Hassan die?

She passed away from lung cancer on August 13, 2000, in London, United Kingdom, at age 35.

Why is Nazia Hassan still remembered today?

Her music remains timeless, her pioneering contributions to pop music are celebrated, and she continues to inspire generations of South Asian artists