In recent years, few slogans in Pakistan have generated as much debate, emotion, and division as “Mera Jism Meri Marzi.” Chanted on streets, printed on placards, debated on television screens, and argued over on social media, the phrase has become one of the most recognizable — and controversial — expressions linked to women’s rights in the country.

To some, it represents dignity, consent, and protection from violence. To others, it sounds provocative, foreign, or morally unsettling. Between these opposing interpretations lies a complex social reality shaped by history, culture, religion, media narratives, and lived experiences of Pakistani women

Literal Meaning of Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” is an Urdu phrase that translates directly into English as “My body, my choice.”

On a literal level, the words are simple:

- Mera means “my”

- Jism means “body”

- Meri means “my”

- Marzi means “choice” or “will”

However, slogans rarely survive on literal meanings alone. Their power — and controversy — comes from what people think they imply.

Conceptual Meaning: Beyond Translation – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

Conceptually, the slogan refers to bodily autonomy — the idea that a person has the right to make decisions about their own body without coercion, violence, or fear.

In the Pakistani feminist context, it has been used to highlight issues such as:

- Consent

- Sexual harassment

- Domestic violence

- Forced marriages

- Honor-based violence

- Reproductive autonomy

- Control over women’s mobility, education, and healthcare

Supporters argue that the slogan is not about rebellion or indecency, but about protection and agency in a society where women’s bodies are often regulated by families, communities, and institutions.

Global Roots: “My Body, My Choice”

The phrase did not originate in Pakistan. Its English version, “My body, my choice,” has been used internationally for decades, particularly in movements advocating for:

- Reproductive rights

- Medical consent

- Protection against sexual violence

The slogan gained global prominence during debates around abortion laws, healthcare access, and bodily consent in Europe and North America.

Pakistani activists later translated the phrase into Urdu, making it locally accessible while retaining its core idea.

Why Translation Became Controversial

Language carries cultural weight. While “my body, my choice” has an established political history in the West, its Urdu translation entered a very different social environment.

In Pakistan:

- Discussions about bodies are often considered taboo

- Women’s sexuality is heavily policed

- Modesty is linked to family honor

- Public discourse is influenced by religious sensitivity

As a result, the slogan’s directness shocked many who were unaccustomed to hearing women publicly assert ownership over their bodies.

First Appearance in Pakistan – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” first appeared prominently during the Aurat March in 2018.

The Aurat March is an annual women’s rights demonstration held on 8 March, International Women’s Day. Initially organized in major cities like Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad, it aimed to highlight structural gender inequalities in Pakistan.

Among many placards and chants, “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” quickly stood out — not because it was the most frequent slogan, but because it was the most debated.

Early Public Reaction – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

From the very beginning, reactions were polarized.

Supportive reactions included:

- Women relating the slogan to harassment and consent

- Activists framing it as a demand for safety

- Young people seeing it as long-overdue honesty

Critical reactions included:

- Claims that it promoted vulgarity

- Accusations of being “un-Islamic”

- Fears of moral decline

- Concerns about Western influence

The slogan soon moved beyond the march itself and entered mainstream debate.

Celebrity Interpretation: Mahira Khan’s Explanation

One of the most widely shared explanations came from actress Mahira Khan, who attempted to clarify the slogan’s intent.

Her words, shared widely in Urdu, stated:

“جب میں کہتی ہوں میرا جسم میری مرضی،

تو اس کا مطلب یہ نہیں کہ میں بے لباس گھومنا چاہتی ہوں۔

اس کا مطلب یہ ہے کہ میں ایک انسان ہوں

اور یہ میرا جسم ہے،

اور مجھے حق ہے کہ میں فیصلہ کروں

کہ کون اسے دیکھے یا چھوئے — یا نہ چھوئے۔”

This explanation became a reference point for supporters who argued that the slogan was being deliberately misinterpreted.

Cultural Context: Why the Phrase Felt Disruptive

In Pakistan, a woman’s body is often seen as:

- A family responsibility

- A symbol of honor

- A site of moral judgment

From childhood, girls are taught how to sit, dress, speak, and behave “properly.” Decisions about marriage, mobility, and even healthcare are frequently influenced by others.

Against this backdrop, a woman publicly declaring ownership over her body challenges long-standing power structures — even if the intent is protection rather than provocation.

Slogan as a Conversation Starter – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

Whether welcomed or rejected, the slogan succeeded in one major way: it forced a conversation.

Topics previously discussed in whispers — consent, abuse, control, autonomy — entered public discourse. Television talk shows, courtrooms, classrooms, and family living rooms began debating questions that had long been ignored.

This unintended consequence became one of the slogan’s most significant impacts.

Why Understanding Matters – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

Understanding what “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” means — and what it does not mean — is essential before judging its role in Pakistani society.

It is not a single idea, but a reflection of multiple lived experiences:

- Of women facing harassment

- Of survivors of violence

- Of families fearing cultural erosion

- Of institutions struggling with change

BACKGROUND AND SOCIAL CONDITIONS THAT LED TO MERA JISM MERI MARZI

Introduction: A Slogan Does Not Appear in a Vacuum

Slogans do not emerge randomly. They are born from pressure — social, cultural, political, and emotional. “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” did not suddenly appear in Pakistan because of a trend or foreign influence. It surfaced because certain realities had existed for decades, largely unaddressed, accumulating frustration and silence.

To understand why this slogan emerged, it is essential to examine the deeper social conditions that shape women’s lives in Pakistan.

mera jism meri marziPatriarchy as a Social Structure – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

Pakistan is a deeply patriarchal society, not only in law but in everyday practice. Patriarchy here does not function only through men; it operates through families, traditions, and expectations passed down generations.

From an early age, boys and girls are socialized differently:

- Boys are encouraged to speak, roam, decide, and lead

- Girls are taught adjustment, obedience, and silence

A woman’s body, choices, and mobility are often seen as collective property — something to be managed “for her own good.”

This environment laid the groundwork for a slogan that directly challenged ownership.

Control Over Women’s Bodies in Daily Life – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Aurat March

Control over women’s bodies in Pakistan often appears subtle, normalized, and unquestioned.

Examples include:

- Deciding what a woman should wear to “avoid attention”

- Restricting movement without male permission

- Monitoring phone usage and friendships

- Pressuring women into marriages they did not choose

- Expecting silence in cases of abuse

These controls are rarely labeled as violence, yet they deeply affect bodily autonomy.

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” directly confronted this normalization.

Sexual Harassment and Public Spaces

For decades, Pakistani women have navigated public spaces with fear:

- Street harassment

- Staring and comments

- Unwanted touching in buses and markets

- Victim-blaming when harassment is reported

Many women grow up hearing:

“تم باہر کیوں نکلی تھیں؟”

“کپڑے ٹھیک نہیں پہنے تھے؟”

The burden of safety is placed on women, not perpetrators.

The slogan became a way of saying: responsibility does not lie on how a woman exists — it lies on those who violate boundaries.

Silence Around Consent – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Status

One of the most critical background issues is the absence of a clear cultural understanding of consent.

In many contexts:

- Consent is assumed after marriage

- Silence is taken as agreement

- Women are discouraged from saying “no”

Marriage itself is often treated as lifelong consent, particularly in intimate matters.

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” reintroduced a word rarely centered in public discourse: consent.

Forced Marriages and Family Pressure – Mera Jism Meri Marzi Woman

Despite legal restrictions, forced and coerced marriages continue in various forms:

- Emotional pressure

- Economic dependence

- Threats of dishonor

- Social isolation

Women who resist are often accused of selfishness or immorality.

The slogan resonated strongly with women whose life decisions — especially marriage — were made without their consent.

Honor-Based Violence and Bodily Control

Pakistan has a long history of honor-based violence, where women are punished for:

- Choosing their own partners

- Seeking divorce

- Alleged relationships

- Exercising independence

In such cases, a woman’s body is treated as a carrier of family honor, not her own identity.

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” directly opposed this logic by asserting that honor cannot exist without consent and dignity.

Legal Gaps and Weak Enforcement

Although Pakistan has laws addressing harassment and violence, implementation remains inconsistent.

Common challenges include:

- Reluctance to register FIRs

- Social pressure on victims to settle

- Character assassination of complainants

- Lengthy court processes

When institutions fail to protect, slogans become tools of resistance.

Religious Interpretation and Misuse

Islamic teachings emphasize consent, dignity, and justice. However, cultural practices often override religious principles.

Many women find that:

- Religion is used selectively to control them

- Cultural customs are justified as religious obligations

- Male authority is mistaken for divine authority

This gap between religious ideals and lived realities contributed to the frustration that fueled feminist expression.

Generational Shift and Youth Awareness

Another key background factor was a generational shift.

Younger Pakistanis:

- Are more exposed to global conversations

- Question inherited norms

- Use social media to express dissent

- Are less willing to accept silence as virtue

For many young women, “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” articulated feelings they had struggled to name.

Influence of Global Movements

The global #MeToo movement also played a role.

Stories of harassment and abuse worldwide encouraged Pakistani women to:

- Share their experiences

- Recognize patterns of abuse

- Demand accountability

While the slogan was localized, the courage to speak openly was globally inspired.

Celebrity Reflection: Sanam Saeed

Actress Sanam Saeed once remarked in Urdu during an interview:

“عورت کا جسم بحث کا موضوع نہیں ہونا چاہیے،

عورت کی مرضی ہونی چاہیے۔

یہ اتنی سادہ بات ہے،

مگر ہم نے اسے مشکل بنا دیا ہے۔”

Her words echoed what many women felt — that the issue itself was simple, but societal resistance made it complex.

Why the Timing Mattered

The slogan emerged at a time when:

- Social media amplified voices

- Women were organizing collectively

- Silence was being questioned

- Traditional authority was being challenged

Had it appeared decades earlier, it may have been suppressed. Appearing now, it sparked national debate.

From Conditions to Expression

All these factors — patriarchy, violence, silence, weak enforcement, generational change — converged into a moment where a direct, emotionally charged slogan felt necessary.

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” was not created to offend; it was created to be heard.

WHO INTRODUCED MERA JISM MERI MARZI AND WHY IT BECAME FAMOUS

Introduction: From a Placard to a National Debate

Not every slogan survives beyond a protest. Many appear briefly, trend for a day, and disappear. “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” followed a different trajectory. It moved from handwritten placards to prime-time television debates, courtrooms, memes, and official advisories.

Understanding who introduced it and how it spread explains why it became the most talked-about slogan of the Aurat March.

The Role of Aurat March Organizers

The slogan was first seen publicly during the Aurat March in 2018. It was not trademarked, authored, or claimed by any single individual.

The Aurat March itself was organized by a collective of activists, academics, lawyers, students, and grassroots workers. Their aim was to create a space where women could articulate their experiences without censorship.

Within this open framework, participants were encouraged to:

- Create their own placards

- Use language that reflected lived realities

- Challenge silence and stigma

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” emerged organically within this environment.

Was There a Single Creator?

There is no verified individual who can be credited as the sole creator of the slogan in Pakistan.

This lack of authorship became one of its strengths:

- It belonged to everyone

- It could not be dismissed as one person’s agenda

- It reflected collective experience rather than ideology

Critics often asked, “کس نے یہ نعرہ بنایا؟”

Supporters responded, “یہ نعرہ حالات نے بنایا۔”

Why This Slogan Stood Out

Many slogans were raised during the Aurat March, yet this one eclipsed others.

Key reasons include:

- Direct language

- Emotional clarity

- Personal ownership

- Cultural discomfort with bodily discourse

Unlike abstract demands, the slogan spoke in first person. It did not ask — it asserted.

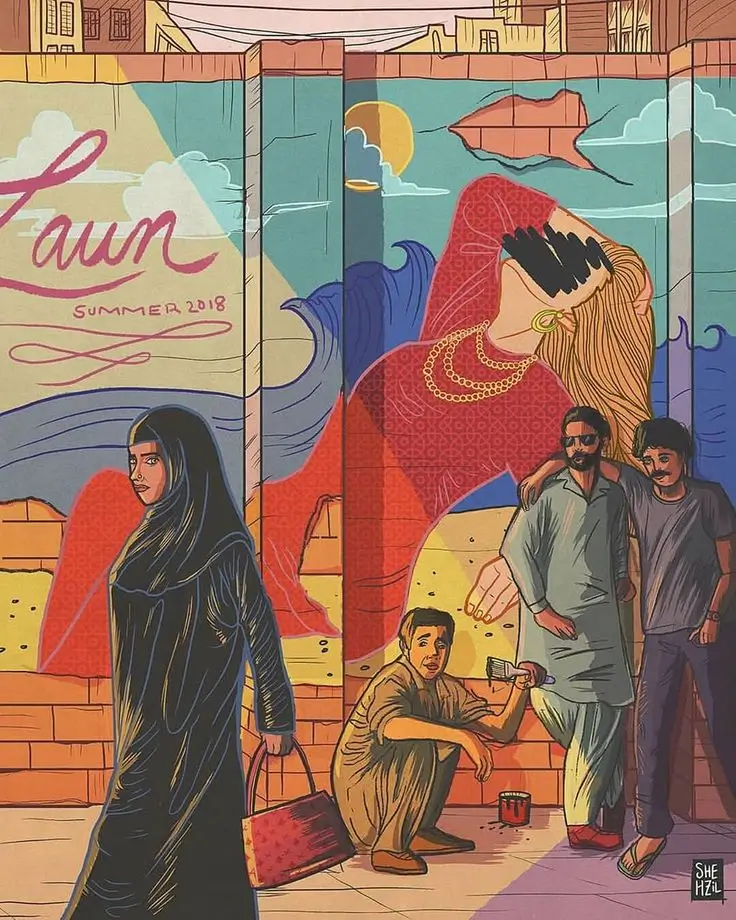

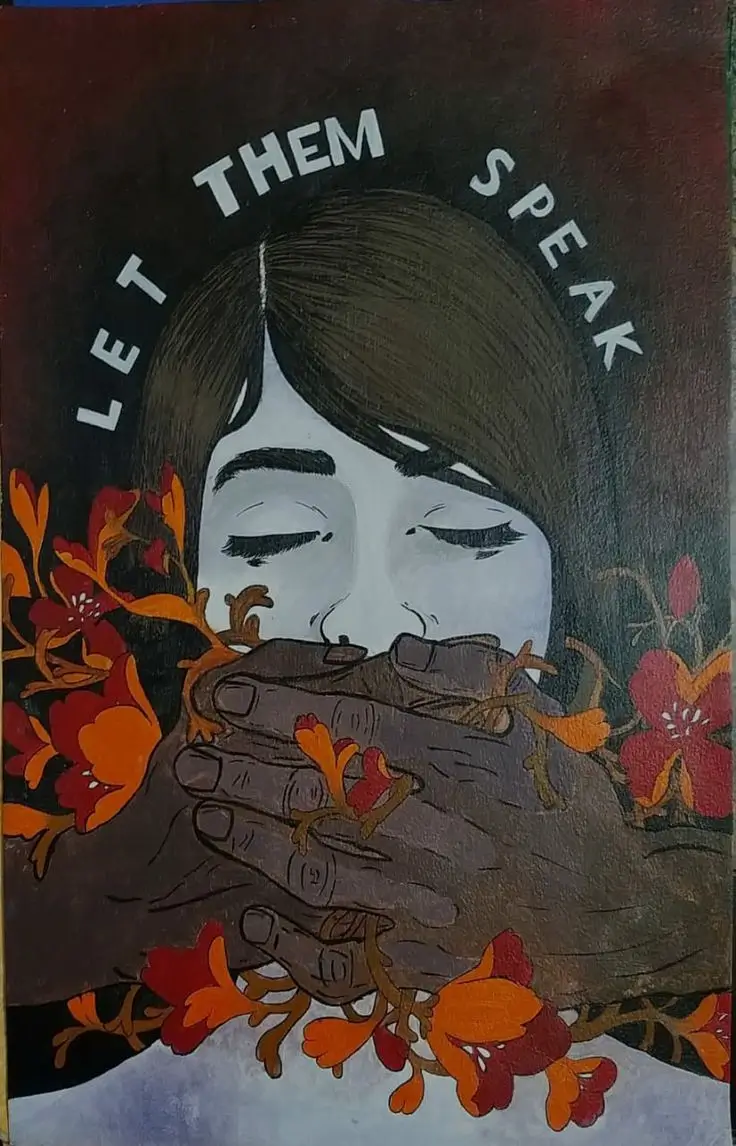

Visual Impact and Media Framing

Television cameras gravitate toward controversy.

Placards bearing “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” were:

- Short

- Visually bold

- Emotionally charged

Media outlets repeatedly zoomed in on these signs, often ignoring others that addressed education, wages, or healthcare.

This selective framing amplified the slogan far beyond its actual frequency at the march.

Social Media as an Accelerator

Once images and clips reached social media, the slogan took on a life of its own.

It became:

- A hashtag

- A meme

- A debate trigger

- A political talking point

Supporters shared explanations and personal stories. Opponents shared mockery and outrage. Algorithms rewarded engagement — not nuance.

Why Opposition Fueled Fame

Ironically, resistance made the slogan famous.

Religious condemnations, political statements, and media outrage:

- Kept the slogan in headlines

- Introduced it to audiences unfamiliar with the Aurat March

- Turned it into a symbol rather than a phrase

What could have remained a niche expression became a national controversy.

The Psychology of Discomfort

The slogan touched three deeply sensitive areas simultaneously:

- Body

- Choice

- Women’s autonomy

For many, it felt like:

- A challenge to authority

- A disruption of norms

- A loss of control

Discomfort often transforms into anger when people feel threatened — even if the threat is symbolic.

Celebrity Endorsements and Clarifications

Several Pakistani celebrities attempted to explain or support the slogan.

Actress Saba Qamar stated in Urdu during a discussion:

“اگر ایک عورت یہ کہے کہ اس کے جسم پر اس کا حق ہے،

تو اس میں فحاشی کہاں ہے؟

یہ تو بنیادی انسانیت ہے۔”

Such statements humanized the slogan for some — while angering others who viewed celebrity support as elitist.

Counter-Slogans and Mockery

As the slogan gained popularity, it also inspired backlash slogans and parody marches.

Examples included:

- “Meri Nazrein Meri Marzi”

- “Apni Chupkalli Khud Maro”

- “Khana Khud Garam Karo” (used both seriously and mockingly)

These responses further embedded the original slogan into popular culture.

Political Use and Misuse

Politicians referenced the slogan to:

- Appeal to conservative voters

- Accuse opponents of moral decay

- Frame feminism as a threat

Once political actors adopted it as a talking point, its visibility multiplied.

Why Fame Came at a Cost

Becoming famous also meant becoming simplified.

For many Pakistanis, the slogan became:

- A symbol of moral fear

- A shorthand for “Westernization”

- A threat to family values

Complex explanations struggled to compete with viral outrage.

Actress’s Reflection: Mehwish Hayat

Mehwish Hayat once remarked in Urdu:

“ہم نعروں پر لڑ رہے ہیں،

مسئلوں پر نہیں۔

اگر مسئلے سن لیے جائیں،

تو شاید نعرے بھی کم ہو جائیں۔”

Her statement highlighted how attention shifted from issues to language.

From Movement to Marker

By 2019, “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” was no longer just a slogan. It became:

- A marker of ideological identity

- A litmus test for opinions

- A dividing line in public debate

Support or opposition to it often defined where someone stood politically and culturally.

Why It Could Not Be Ignored

The slogan endured because it addressed unresolved realities:

- Violence

- Silence

- Control

- Fear

Even those who rejected it could not avoid discussing it.

HOW MERA JISM MERI MARZI IS USED: ACTIVISM, MEDIA, AND EVERYDAY DISCOURSE

Introduction: A Slogan That Changes Shape

Once a slogan enters public consciousness, it no longer belongs to a single movement. “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” has been used, reused, reinterpreted, and sometimes distorted depending on who is speaking and why.

This series examines how the slogan functions across different spaces — from protests to classrooms, from social media to television debates — and how its meaning shifts with context.

Use in Street Protests and Marches

The most visible use of the slogan remains within the Aurat March.

At marches, it is typically used to:

- Assert bodily autonomy

- Demand safety in public spaces

- Highlight consent and dignity

- Protest gender-based violence

On placards, it often appears alongside explanations, such as:

- “Mera jism meri marzi, zabardasti nahi”

- “Consent zaroori hai”

For many participants, the slogan is less about provocation and more about collective affirmation.

Chanting Versus Display

There is an important distinction between chanting and displaying the slogan.

- When chanted, it becomes a collective voice

- When written, it invites interpretation

Written placards allowed people to project their fears or beliefs onto the phrase, which partly explains the intensity of reaction.

Use in Educational and Academic Spaces

Universities and student groups have used the slogan in seminars and discussions about:

- Gender studies

- Human rights

- Constitutional protections

- Sociology and law

In these settings, it is often unpacked carefully, with emphasis on consent, agency, and legal frameworks.

However, even in academic spaces, the slogan has faced resistance from administrations wary of controversy.

Social Media Usage and Hashtags

Social media transformed the slogan into a digital battleground.

Supporters use hashtags to:

- Share survivor stories

- Explain personal interpretations

- Connect local issues to global conversations

Opponents use counter-hashtags to:

- Mock the phrase

- Frame it as immoral

- Link it to foreign agendas

This polarized usage reduced nuance and rewarded extreme positions.

Meme Culture and Satire

Memes played a significant role in popularizing the slogan — often in mocking ways.

While satire is a form of political expression, it also:

- Oversimplified the debate

- Reinforced stereotypes

- Shifted focus from violence to ridicule

For many women, this trivialization felt dismissive of real pain.

Television Talk Shows and Panel Debates

Pakistani talk shows became major arenas for the slogan’s interpretation.

Common features included:

- Shouting matches

- Moral panic framing

- Male-dominated panels discussing women’s bodies

- Limited space for lived experiences

Rather than clarifying the slogan, many programs amplified confusion.

Celebrity Advocacy and Explanation

Celebrities used their platforms to interpret the slogan for broader audiences.

Actor Ayesha Omar stated in Urdu during an interview:

“یہ نعرہ بے حیائی کی دعوت نہیں،

یہ حفاظت کی بات ہے۔

اگر عورت خود کو محفوظ کہہ سکے،

تو معاشرہ بھی محفوظ ہوتا ہے۔”

Such explanations attempted to ground the slogan in safety rather than shock.

Use by NGOs and Rights Groups

Human rights organizations adopted the slogan in campaigns addressing:

- Harassment laws

- Domestic violence awareness

- Consent education

- Women’s healthcare access

In these contexts, it functioned as shorthand for bodily rights rather than rebellion.

Misuse and Deliberate Distortion

Not all uses were honest.

The slogan was sometimes:

- Quoted without context

- Paired with unrelated imagery

- Used to provoke outrage intentionally

This deliberate distortion widened the gap between intent and perception.

Family and Private Conversations

Perhaps the most significant use occurred privately.

Many women reported that the slogan:

- Helped them articulate boundaries

- Sparked difficult family conversations

- Gave language to previously unspoken discomfort

Even when rejected, it forced acknowledgment.

Religious and Cultural Reframing Attempts

Some scholars and activists attempted to reframe the slogan within Islamic ethics, emphasizing:

- Consent in marriage

- Prohibition of harm

- Dignity of the human body

These attempts sought to bridge divides, though they rarely gained equal media attention.

Actor’s Reflection: Humayun Saeed

Actor Humayun Saeed commented in Urdu:

“مسئلہ نعرے کا نہیں،

مسئلہ سننے کا ہے۔

اگر بات سن لی جائے،

تو لفظ خود بخود نرم ہو جاتے ہیں۔”

His remark highlighted listening as the missing element.

A Slogan With Multiple Lives

Depending on context, “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” functions as:

- A protest cry

- An educational tool

- A social media symbol

- A moral panic trigger

- A personal boundary statement

These multiple lives explain both its reach and its controversy.

Why Usage Matters

How a slogan is used determines how it is understood.

Selective usage, sensational framing, and mockery shaped public perception as much as original intent.

In the next series, we will analyze the impact of the slogan — socially, culturally, and politically — and whether it has led to measurable change or primarily symbolic conflic

IMPACT OF MERA JISM MERI MARZI ON SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND POLITICS

Introduction: Measuring Impact Beyond Noise

Impact is not always immediate or measurable through laws alone. Sometimes, impact appears as discomfort, debate, and disruption. “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” has not rewritten Pakistan’s legal system, but it has undeniably reshaped conversations around women’s rights.

This series examines the social, cultural, political, and psychological effects of the slogan.

Shifting Public Conversation

Before the slogan, many issues remained largely unspoken in mainstream discourse:

- Consent within marriage

- Sexual harassment by acquaintances

- Control disguised as protection

- Women’s right to say no

After the slogan gained prominence, these topics began appearing — however imperfectly — in:

- Television debates

- School discussions

- Family arguments

- Policy conversations

Silence was broken, even if resistance followed.

Empowerment Through Language

For many women, the slogan provided language for experiences they struggled to articulate.

Being able to say:

- “یہ میری مرضی نہیں تھی”

- “مجھے حق ہے انکار کا”

Helped validate personal boundaries.

Language shapes thought. Naming a right makes it harder to deny.

Impact on Younger Generations

Among younger Pakistanis, especially students, the slogan:

- Encouraged questioning of norms

- Opened dialogue about consent

- Challenged inherited gender roles

Even disagreement forced engagement.

Teachers and parents reported that young people asked more direct questions about autonomy and respect.

Cultural Pushback and Polarization

Impact also came in the form of backlash.

The slogan:

- Deepened ideological divides

- Reinforced conservative resistance

- Became a symbol of cultural anxiety

For some, it represented a loss of moral certainty rather than a demand for rights.

Polarization itself became an outcome.

Influence on Feminist Discourse

Feminist activism in Pakistan became more visible and more contested.

The slogan:

- Gave feminism a recognizable marker

- Made women’s movements harder to ignore

- Also made them easier to attack

Visibility came with vulnerability.

Media Impact: Ratings Over Responsibility

Media houses benefited from the controversy.

Debates featuring the slogan:

- Attracted high viewership

- Encouraged sensational framing

- Often sidelined nuance

While awareness increased, understanding often decreased.

Legal and Policy Conversations

Although no law was passed because of the slogan, it:

- Highlighted gaps in harassment enforcement

- Drew attention to victim-blaming in legal processes

- Pressured institutions to address consent terminology

Lawyers and rights groups referenced the slogan while advocating for stronger protections.

Law Enforcement Sensitivity

The slogan indirectly influenced conversations around:

- Police handling of harassment cases

- FIR registration reluctance

- Training on gender sensitivity

However, structural change remained slow and uneven.

Political Impact and Rhetoric

Politicians used the slogan strategically:

- Conservatives framed it as moral decline

- Liberals defended it as free expression

It became a political shorthand rather than a policy discussion.

Celebrity Influence on Impact

Celebrity support amplified reach.

Actress Mahira Khan’s earlier clarification softened perceptions for some audiences.

Actor Fahad Mustafa remarked in Urdu:

“اگر عورت خود کو محفوظ محسوس نہیں کرتی،

تو نعرے نہیں،

خاموشی زیادہ خطرناک ہے۔”

Such statements reframed the issue as safety rather than ideology.

Psychological Impact on Women

For many women, the slogan:

- Reduced isolation

- Affirmed shared experience

- Validated anger and frustration

Even when criticized, it reassured women that they were not alone.

Impact on Men’s Awareness

Though often resistant, some men reported that:

- The slogan forced self-reflection

- Conversations with sisters and daughters changed

- Awareness of boundaries increased

Impact is rarely uniform — it arrives unevenly.

Limitations of the Impact

Despite attention, many realities remained unchanged:

- Violence persisted

- Reporting remained risky

- Social stigma continued

A slogan alone cannot dismantle structural inequality.

Net Impact: Progress or Polarization?

The slogan’s impact can be summarized as:

- Increased visibility

- Heightened debate

- Limited structural change

- Deepened polarization

Whether this is progress depends on perspective

CONTROVERSIES, CRITICISM, LAW ENFORCEMENT, AND INSTITUTIONAL RESPONSE

Introduction: When a Slogan Meets Authority

When “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” moved from streets to screens, it inevitably collided with institutions of power — religious bodies, courts, regulatory authorities, and law enforcement. This series examines why the slogan became controversial, how institutions responded, and what this reveals about freedom of expression and gender politics in Pakistan.

Religious Criticism and Moral Anxiety

One of the strongest reactions came from religious scholars and groups.

Common objections included:

- The slogan encourages immorality

- It undermines family structure

- It promotes Western values

- It weakens religious authority

Friday sermons, television lectures, and social media clips framed the slogan as a moral threat rather than a rights-based demand.

However, critics rarely engaged with feminist explanations centered on consent and protection.

Selective Religious Interpretation

A major point of contention was selective interpretation.

Supporters argued that:

- Islam emphasizes consent in marriage

- Harm is explicitly forbidden

- Human dignity is central to faith

Opponents countered by framing public discussion of bodily autonomy as indecent.

This clash revealed tension between religious principles and cultural practices.

Political Controversies and Parliamentary Reaction

The slogan reached parliament when:

- Members raised concerns about “immorality”

- Committees labeled it inappropriate

- Political speeches referenced it as cultural decline

Rather than debating gender violence statistics or enforcement failures, discussion often centered on language.

This shift deflected attention from substantive issues.

Media Regulatory Response (PEMRA)

One of the most significant institutional actions came from the Pakistan Electronic Media Regulatory Authority.

PEMRA issued advisories discouraging or restricting the broadcast of:

- The slogan itself

- Visuals associated with Aurat March

- Discussions deemed “against societal norms”

This raised concerns about censorship and selective moral regulation.

Court Cases and Judicial Stance

Several petitions were filed to ban the Aurat March and its slogans.

Key outcomes included:

- Courts allowed marches under constitutional rights

- Petitioners were asked to explain how slogans violated Islam

- Blanket bans were rejected

While courts did not endorse the slogan, they upheld the right to protest.

Law Enforcement on the Ground

Police responses to Aurat March events varied by city.

Observed patterns included:

- Heavy security presence

- Monitoring of placards

- Lack of proactive protection against harassment

While law enforcement did not directly suppress marches, they did not actively defend participants from threats either.

FIRs, Threats, and Online Abuse

Activists and participants faced:

- Online threats

- Doxxing

- Character assassination

- Intimidation

Few cases resulted in meaningful police action, reinforcing perceptions of institutional indifference.

Public Controversies and Talk Show Incidents

One of the most infamous controversies involved a televised argument between a writer and a feminist activist.

The exchange included:

- Sexist remarks

- Personal attacks

- Public outrage

This incident symbolized how quickly discussion shifted from rights to hostility.

Celebrity Backlash and Targeting

Celebrities who supported the slogan faced:

- Boycott calls

- Moral policing

- Online abuse

Actress Mahira Khan, despite her clarification, was heavily criticized.

Singer Shehzad Roy commented in Urdu:

“ہم عورت کے لفظوں سے ڈر جاتے ہیں،

مگر ظلم سے نہیں۔

یہی ہمارا مسئلہ ہے۔”

His statement highlighted misplaced outrage.

Institutional Silence on Violence

Ironically, institutions that reacted strongly to the slogan were often silent on:

- Honor killings

- Domestic violence cases

- Harassment scandals

This contrast deepened feminist critique of moral selectivity.

The State’s Dilemma

The state faced a dilemma:

- Protect freedom of expression

- Maintain cultural sensitivity

- Avoid political backlash

The result was ambiguity — neither full protection nor outright suppression.

Did Controversy Help or Harm?

Controversy:

- Increased visibility

- Hardened opposition

- Discouraged moderate dialogue

For many women, the backlash confirmed the very power imbalance the slogan highlighted.

Actress’s Reflection: Nadia Jamil

Nadia Jamil stated in Urdu during a panel discussion:

“اگر عورت اپنے جسم کی بات کرے،

تو ہنگامہ مچ جاتا ہے۔

لیکن اگر اس جسم پر تشدد ہو،

تو خاموشی چھا جاتی ہے۔”

Her words captured the contradiction at the heart of the controversy.

Where Institutions Stand Today

As of now:

- No legal ban exists on the slogan

- Media self-censorship is common

- Law enforcement remains reactive

- Courts uphold protest rights cautiously

The slogan exists in a legal grey zone — allowed, but discouraged

POSITIVE AND NEGATIVE IMAGE, PUBLIC PERCEPTION, MEDIA, CELEBRITIES, AND LEGACY

Introduction: Beyond the Slogan

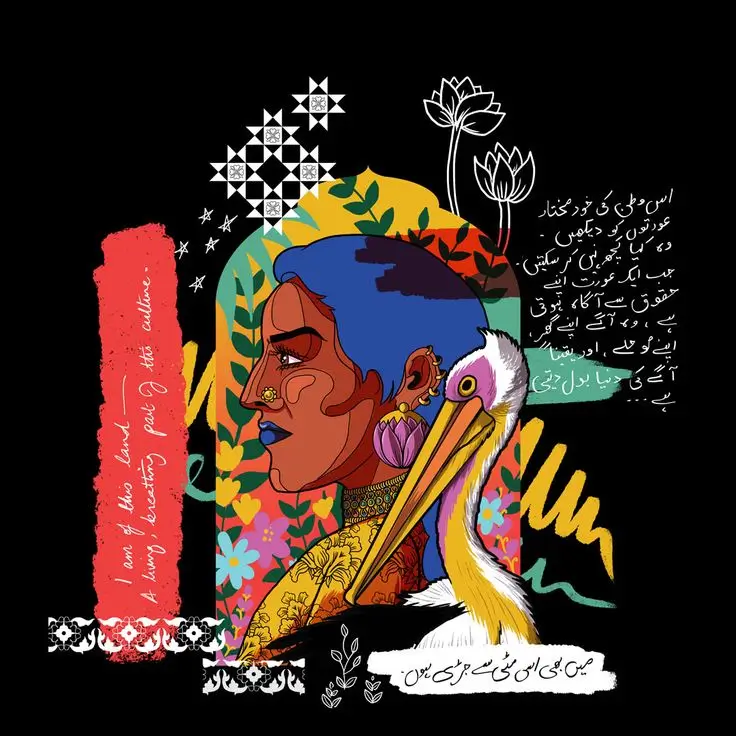

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” is no longer just a phrase — it has become a symbol, a conversation starter, and, for many, a lightning rod. Understanding its image requires weighing both admiration and criticism, the role of media and celebrities, and its long-term impact on Pakistani society.

Positive Image: Empowerment and Awareness

The slogan’s supporters see it as a movement for autonomy, dignity, and safety:

- Empowerment: Women and allies view it as reclaiming control over personal decisions.

- Awareness: It brought conversations about harassment, consent, and reproductive rights into public discourse.

- Solidarity: The Aurat March and related events created a sense of community among women across cities.

- Global Visibility: International media coverage placed Pakistan in a wider human rights conversation.

Celebrity endorsements amplified this positive image:

- Mahira Khan expressed support, highlighting women’s struggles without fear.

- Shehzad Roy in his social commentary said:

“عورت کا حق ہے کہ وہ اپنے جسم پر خود فیصلہ کرے،

یہ حقوق کسی سے کم نہیں ہیں۔”

Media coverage in certain outlets focused on these human rights and equality narratives, helping to normalize discussions previously considered taboo.

Negative Image: Misinterpretation and Backlash

Critics, however, framed the slogan as:

- Immoral or indecent: Many religious and conservative voices argued it encouraged promiscuity.

- Culturally alien: Some believed it reflected Western influence.

- Provocative: The confrontational phrasing led opponents to view it as aggressive rather than protective.

Social media amplified negative perceptions through trolling, memes, and misinformation campaigns. Select talk shows portrayed the slogan as a symbol of social chaos, rather than a campaign for consent.

Public Perception

- Youth: Many young Pakistanis, especially urban students, embraced the slogan as progressive.

- Conservative population: Older or rural populations often misunderstood its intent, reacting with hostility.

- General population: The conversation split along generational, educational, and urban-rural lines.

The divide reflects a broader cultural negotiation between tradition and modern feminist movements.

Media Framing

The media played a dual role:

- Amplifying debate: Coverage in newspapers, TV, and social media gave the slogan visibility.

- Polarizing narratives: Some channels presented it as provocative or dangerous, emphasizing moral outrage over gender rights.

For example, Dawn News and The Express Tribune often focused on legal rights and activism, while sensationalist channels highlighted conflict and public outrage.

Celebrity Influence

Celebrities shaped both positive and negative reception:

- Positive support: Advocates increased visibility and normalized discussions on consent.

- Criticism: Endorsers faced harassment, demonstrating society’s discomfort with public women’s autonomy.

Quotes from celebrities in Urdu captured the essence:

- Nadia Jamil:

“ہماری آواز دبائی نہیں جا سکتی،

جسم ہمارا ہے، اختیار ہمارا ہے۔” - Shehzad Roy:

“ہم ظلم کے خلاف بولتے ہیں،

تو تنقید کا سامنا کرنا پڑتا ہے،

مگر خاموشی کوئی حل نہیں۔”

Legal and Social Legacy

- Legal: Courts have upheld the right to protest, keeping the slogan legally protected.

- Social: Open debates on consent, harassment, and reproductive rights became more mainstream.

- Cultural: Even among critics, the discussion forced engagement with previously avoided topics.

Positive vs Negative Summary

| Positive Impact | Negative Impact |

|---|---|

| Empowerment of women | Viewed as immoral or provocative |

| Awareness of consent, harassment, and bodily rights | Misinterpreted as Western or anti-cultural |

| Strengthened solidarity among activists | Backlash from religious, political, and conservative groups |

| Global recognition of Pakistani women’s rights movements | Online harassment and targeting of supporters |

| Encouraged open public discourse | Polarization in society and media |

Concluding Thought

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” may never be universally accepted, but it has redefined conversations about women’s autonomy in Pakistan. Its impact extends beyond slogans into legal debates, media discourse, and cultural norms, reflecting both resistance and progress.

The slogan’s journey shows that visibility, even amid controversy, can spark change:

“اگر ہم اپنے حق کے لیے خاموش رہیں،

تو تاریخ ہمیں نہیں یاد کرے گی۔” – (Popularized in feminist discourse, Urdu)

In the end, whether celebrated or criticized, the slogan represents a turning point in Pakistan’s struggle for women’s rights, marking a cultural shift that will continue to evolve in the years ahead.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) – “Mera Jism Meri Marzi”

1. What does “Mera Jism Meri Marzi” mean?

“Mera Jism Meri Marzi” is an Urdu phrase meaning “My body, my choice.” It’s a feminist slogan used to emphasize that individuals should have autonomy and control over their own bodies.

2. Where did the slogan originate?

The slogan was popularized in Pakistan during the Aurat March, an annual women’s rights march first held in 2018 and timed with International Women’s Day.

3. Why do people use this slogan?

Supporters use it to protest gender-based violence, sexual harassment, denial of consent, and social norms that restrict women’s choices regarding their bodies and lives.

4. Is it related to the English slogan “My body, my choice”?

Yes — it is essentially the Urdu equivalent of the English slogan “My body, my choice,” which has been used globally in feminist and reproductive rights movements.

5. Why is the slogan controversial in Pakistan?

It has sparked debate because some view it as contradicting traditional cultural or religious norms, while supporters argue it challenges patriarchal control over women’s bodies.

6. Does it mean what critics claim (like promoting nudity or immorality)?

No — activists and figures like Mahira Khan have clarified that it doesn’t promote nudity or immorality; rather it means a person has the right to refuse unwanted attention, touching, or harassment.

7. What issues are associated with the slogan beyond the phrase itself?

While it focuses on bodily autonomy, it’s also linked in discourse to broader issues such as harassment, forced marriages, gender discrimination, and social freedoms.

8. Has the slogan appeared in broader Pakistani culture?

Yes — artists and influencers have referenced or reinterpreted it in music and social media to highlight women’s rights and confront misconceptions.