The Kalash people are one of the most fascinating, ancient, and culturally distinct communities of South Asia. Nestled deep within the mountainous terrain of northern Pakistan, the Kalash have managed to preserve a unique identity that stands apart from surrounding societies. Their religion, traditions, clothing, festivals, and worldview reflect a living heritage that predates many modern civilizations. Despite centuries of pressure, isolation, and external influences, the Kalash continue to safeguard their way of life, making them a symbol of cultural resilience and indigenous survival.

Where Are the Kalash People Located

The Kalash people live in the remote mountainous region of Chitral District, located in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) province of Pakistan.

Their homeland consists of three narrow valleys tucked away in the Hindu Kush mountain range:

Bumburet (also known as Bamboret or Bumbarat)

Rumbur

Birir

These valleys are collectively referred to as the Kalash Valleys. Surrounded by towering snow-capped peaks, dense forests, flowing streams, and alpine meadows, these Valleys are among the most scenic regions of Pakistan. The natural beauty of the area contrasts sharply with the social and cultural challenges faced by its inhabitants.

The Kalash live in approximately 12 small villages, each built along mountain slopes with wooden houses stacked in terraces. These villages are connected by narrow paths rather than wide roads, reinforcing the sense of isolation that has helped preserve these valleys traditions for centuries.

Access to these Valleys is possible from Peshawar and Gilgit, primarily via the Lowari Pass and Shandur Pass, covering distances of roughly 365 to 385 kilometers. The journey by road can take up to 12 hours, depending on weather conditions. In recent years, many visitors prefer to travel by air, using daily Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flights from Islamabad or Peshawar to Chitral, followed by a road journey into the valleys.

Despite improved accessibility, these Valleys remain geographically secluded, which has played a critical role in preserving the Kalash identity.

The Kalash People: An Indigenous Community of Pakistan

The Kalash are widely recognized as an indigenous ethnoreligious minority of Pakistan. They speak Kalasha-mun, a Dardic language belonging to the Indo-Aryan family. Their language, folklore, and oral traditions carry memories of ancient migrations, religious beliefs, and historical struggles.

Unlike most communities in Pakistan, they follow a polytheistic religion, rooted in nature worship, ancestor reverence, and seasonal cycles. This belief system sets them apart from the Muslim-majority population of the region and has historically placed them under social pressure.

According to elders, identity is not just about religion but about land, ancestry, festivals, music, clothing, and shared memory. For them, losing any one of these elements threatens the survival of their entire culture.

Origins of the Kalash People: Myths and Theories

The origins of these valleys people have long been a subject of debate, speculation, and fascination among historians, anthropologists, and travelers. Several theories exist, each supported by oral traditions, folklore, and academic research.

One popular belief claims that the Kalash are descendants of soldiers from Alexander the Great’s army, who settled in the region after the Macedonian invasion of South Asia in the 4th century BC. This theory gained popularity due to the people’s fair complexions, light eyes, and distinctive facial features, which differ from neighboring populations. However, modern genetic research has largely dismissed this claim as a myth rather than historical fact.

Another widely accepted theory suggests that the Kalash are indigenous to the greater Kafiristan region, which historically extended across parts of present-day Chitral (Pakistan) and Nuristan (Afghanistan). These valleys are themselves referred to in their folk songs as ancient homelands, including a distant place called Tsiyam, believed to be somewhere in South Asia.

Historical evidence indicates that these people migrated from areas of Afghanistan into Chitral around the 2nd century BC. By the 10th century AD, they had established political dominance over large parts of present-day Chitral.

Kalash Rule and Early History

Between the 10th and 14th centuries, these people were not a marginalized minority but a powerful group that ruled significant territories.

Historical accounts mention several prominent rulers, including:

Razhawai

Cheo

Bala Sing

Nagar Chao

During this period, Kalash culture flourished. Their religious institutions, festivals, and social structures were firmly established, and they shared cultural similarities with related tribes known historically as the Red Kafirs in neighboring regions of Afghanistan.

The term “Kafir,” meaning non-believer, was used historically to describe communities that did not convert to Islam. The Kalash and their Afghan counterparts maintained similar religious practices, mythologies, and rituals centered on nature, ancestors, and seasonal cycles.

Decline of Kalash Power and Forced Conversions

By the early 14th century, the political and cultural dominance of the Kalash began to decline. Historical records indicate that Shah Nadir Raees played a significant role in subjugating these valleys territories and initiating mass conversions to Islam in southern Chitral.

Villages such as Drosh, Sweer, Kalkatak, Beori, Ashurate, Shishi, and Jinjirate were among the last to be converted during the 14th century. As conversions increased, Kalash territory gradually shrank. The most devastating blow came in 1893, when the Amir of Afghanistan forcibly converted the Red Kafirs of Kafiristan to Islam.

Following this event, the region was renamed Nuristan, meaning “Land of Light.” Those who converted and settled in Chitral became known as Sheikhanandeh, literally “the village of the converted ones.”After this period, the Kalash were confined to just three valleys: Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir, where they remain today.

Kalash Population Decline

The Kalash population has experienced a dramatic decline over the past century. According to surveys conducted by non-governmental organizations, the population decreased from approximately 10,000 individuals in 1951 to about 3,700 by 2010.

Several factors contributed to this decline, including:

Religious pressure and social discrimination

Economic marginalization

Limited access to education and healthcare

Land disputes and deforestation

Interfaith marriages leading to conversions

Migration due to insecurity and fear

Residents of the these Valleys have openly spoken about threats received from outsiders demanding that they abandon their traditions. Many families have either gone underground or left the area entirely, fearing for their safety and cultural survival.

Modern Challenges and Cultural Preservation

Despite these challenges, efforts to preserve Kalash culture have intensified in recent decades. Conservation experts, anthropologists, activists, and community leaders have worked together to document traditions, protect heritage sites, and promote cultural awareness.

One major outcome of these efforts is the Kalasha Dur, meaning “House of the Kalash.” This museum serves as a cultural archive, housing artifacts, clothing, tools, jewelry, musical instruments, and historical records that reflect these Valley life and beliefs.

International interest, including support from Greek-funded organizations, has also played a role in preserving Kalash heritage. Tourism has brought economic opportunities, but it has also introduced new challenges related to cultural commodification and social change.

The Kalash Identity Today

Today, the Kalash stand at a crossroads. They are globally admired for their beauty, festivals, music, and colorful clothing, yet locally vulnerable due to their minority status. The government and local administration provide some protection, but many residents still report feelings of insecurity.

As one villager from Bamoret expressed, they do not want to leave their ancestral land, but fear persists due to continuous threats and pressure to conform.

The Kalash story is not just about an ancient tribe living in isolation; it is about survival, dignity, and the right to exist as a distinct people in the modern world.

Kalash Religion, Beliefs, Gods, Mythology and Sacred Worldview

The religion of these valleys people is the most defining element of their identity and the primary reason they have remained culturally distinct for thousands of years. Unlike the surrounding

Muslim-majority population of northern Pakistan, the Kalash follow an ancient polytheistic belief system rooted in nature, ancestral spirits, seasonal cycles, purity concepts, and cosmic balance.

Their religion is not confined to temples or scriptures; instead, it is deeply embedded in daily life, agriculture, festivals, music, dance, birth, marriage, and death. For the Kalash, religion is not a separate institution—it is a living worldview that governs how humans interact with nature, spirits, and each other.

Foundation of Kalash Religious Belief

Kalash religion is based on the idea that the universe is alive and spiritually interconnected. Mountains, rivers, forests, animals, ancestors, and celestial bodies all possess spiritual significance. Humans exist within this sacred ecosystem and must maintain balance through ritual observance, moral conduct, and respect for tradition.

Central to these valleys belief is the concept of purity and impurity, which shapes social behavior, gender roles, ritual spaces, and festivals. Certain places, times, and activities are considered pure, while others are seen as impure and require separation or cleansing.

This worldview has ancient Indo-Aryan roots and shares similarities with pre-Islamic and pre-Vedic belief systems of the wider Hindu Kush and Central Asian regions.

The Supreme Deity and Kalash Pantheon

At the center of Kalash religion stands Mahandeo, the supreme god and protector of these people. Mahandeo is associated with creation, justice, protection, and moral order. He is believed to watch over the community and punish those who violate sacred laws or abandon tradition.

Alongside Mahandeo, these people worship twelve major gods and goddesses, each responsible for specific aspects of life and nature. These deities are not distant figures but active participants in human affairs.

Some of the most important Kalash deities include:

Balumain, the most revered god associated with winter, renewal, and the sacred festival of Chowmos. He is believed to visit these valleys during the winter solstice, bringing blessings and prosperity.

Sajigor, the god of war and protection, often invoked during times of conflict or danger.

Dezalik, the goddess of childbirth, fertility, and family life. Women seek her blessings during pregnancy and delivery.

Ingaw, associated with health, growth, and prosperity.

Jestak, the goddess of home, family unity, and female lineage. Every Kalash household has a Jestak shrine, making her worship central to domestic life.

These gods and goddesses form a complex spiritual network that governs both public rituals and private household worship.

Ancestor Worship and Spiritual Continuity

Ancestor worship plays a crucial role in Kalash religious life. They believe that the spirits of their ancestors continue to influence the living world. Honoring ancestors ensures protection, fertility, and prosperity for future generations.

This belief is reflected in their elaborate funeral rites, memorial ceremonies, and wooden effigies placed near graves. Unlike many cultures that associate death with fear, the Kalash view it as a transition rather than an end.

Ancestors are believed to intercede with the gods on behalf of the living, making remembrance and ritual offerings essential.

Sacred Spaces and Altars

Kalash religious practice revolves around open-air altars, temples, and sacred groves rather than enclosed buildings. These altars are usually constructed from stone and wood and are placed near rivers, forests, or village centers.

Sacrifices—usually goats or cows—are offered during festivals and major life events. These sacrifices are not acts of violence but sacred exchanges between humans and deities, meant to restore balance and express gratitude.

Each village maintains multiple sacred sites, and certain areas are strictly off-limits to outsiders or individuals considered ritually impure.

The Concept of Purity and Impurity

One of the most misunderstood aspects of Kalash religion is their concept of purity. Purity is not moral judgment but a spiritual state that allows communication with divine forces.

Menstruation and childbirth are considered powerful and spiritually charged states. During these times, women stay in a separate structure called Bashali, located outside the main village settlement.

The Bashali is not a place of punishment but a sacred space where women rest, give birth, and undergo spiritual transitions. Women are allowed to work in fields during menstruation but are not permitted to enter their homes until purification rituals are completed.

This system reflects ancient beliefs about cosmic balance rather than discrimination, although it is often misinterpreted by outsiders.

Role of the Betaan (Shaman)

The Betaan, or shaman, is one of the most important religious figures in Kalash society. He acts as a mediator between the human and spiritual worlds.

The Betaan performs rituals, offers sacrifices, interprets dreams, and makes prophecies. During major festivals, he enters trance-like states and communicates with deities and fairies, seeking guidance for the community.

Kalash mythology holds that supernatural beings, including mountain spirits and fairies, inhabit the surrounding landscape. The Betaan calls upon these beings to restore harmony during times of illness, conflict, or disaster.

Music, Dance, and Religious Expression

Music and dance are not entertainment in Kalash culture; they are sacred acts. Religious rituals are incomplete without rhythmic drumming, chanting, and circular dances performed by men and women together.

According to Kalash belief, music creates a bridge between humans and gods. The vibrations of drums and songs are believed to please deities and invite blessings.

Each festival has its own specific songs, dances, and musical patterns, passed down orally through generations.

Astronomy and Cosmic Beliefs

Astronomy holds a special place in Kalash religious thought. The people closely observe the sun, moon, stars, and seasonal cycles.

They believe that a new sun is born on December 21, the winter solstice. This event marks the beginning of spiritual renewal and is celebrated during the Chowmos festival.

Changes in celestial movements are believed to influence crops, livestock, weather, and human fate. This deep connection to cosmic rhythms reinforces the Kalash respect for nature and time.

Religious Pressure and Threats

The Kalash religion has faced continuous threats due to its polytheistic nature. Traditionalists and extremist elements have repeatedly pressured these families to abandon their beliefs.

Residents of these Valleys report receiving threats demanding conversion. While government protection exists, fear remains a daily reality for many families.

Interfaith marriages, economic vulnerability, and social marginalization have also contributed to religious conversions, accelerating population decline.

Survival of an Ancient Faith

Despite centuries of persecution, forced conversions, and social pressure, the Kalash religion has survived. Its endurance lies in strong community bonds, oral tradition, festivals, and an unwavering attachment to ancestral land.

These Valleys elders emphasize that abandoning religion would mean losing identity, history, and meaning. For them, religion is not optional—it is existence itself.

Kalash Social Structure, Community Organization, Cast, Gender Roles and Daily Life

The social structure of these people is as ancient and distinctive as their religion. Living in the remote valleys of Bumburet, Rumbur, and Birir in the Chitral district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the Kalash have developed a tightly knit community system that governs daily life, social relations, moral conduct, and cultural survival.

Their society is built on kinship, shared rituals, collective responsibility, and a deep connection to land and ancestry.

Unlike rigid caste-based systems found elsewhere in South Asia, this society is relatively egalitarian, yet clearly structured through lineage, clan identity, age, gender roles, and religious responsibility.

Kalash Villages and Community Layout

The Kalash live in around twelve small villages, spread across the three valleys. These villages are constructed on steep mountain slopes, with wooden houses stacked in terraces. Homes are built from stone, mud, and timber, reflecting harmony with the environment.

Each village functions as a self-regulating social unit. Community decisions are taken collectively, and elders play a guiding role rather than an authoritarian one. There is no centralized political authority; instead, social order is maintained through tradition, custom, and religious norms.

Sacred spaces such as altars, temples, and the Jestak house are integral parts of village life, reinforcing the inseparability of religion and social organization.

Clan System and Lineage

Kalash society is organized around clans, which are extended family groups tracing ancestry through the male line. Clan identity determines marriage alliances, social obligations, and ritual participation.

Each clan has its own history, ancestral myths, and responsibilities during festivals. Clan solidarity is crucial, especially during ceremonies, weddings, funerals, and conflict resolution.

Marriage within the same clan is forbidden, ensuring genetic diversity and reinforcing inter-clan relationships.

Is There a Cast System Among the Kalash?

They do not follow a caste system like Hindu society, but there is a social hierarchy based on ritual purity, lineage, and religious role.

Certain families are traditionally associated with priestly or ritual roles, such as providing Betaans (shamans) or ritual specialists.

These roles are not hereditary in a rigid sense but often pass through family lines due to accumulated knowledge and spiritual training. Converted Kalash families, known locally as Sheikhanandeh, often live near Kalash villages but are socially distinct. While many still speak the Kalasha language and follow cultural customs, they are not allowed to participate fully in the religious life.

This separation is not based on hatred but on the belief that religious purity is essential for communal survival.

Role of Elders and Community Leadership

Elders hold moral authority in this society. They act as mediators in disputes, guardians of tradition, and advisors in major decisions.

Leadership is informal and based on respect rather than power. Elders guide the community through consensus, especially in matters related to festivals, land use, marriages, and conflict resolution.

Their authority comes from experience, knowledge of customs, and adherence to tradition.

Gender Roles in Kalash Society

One of the most striking aspects of Kalash society is the visibility and agency of women, especially when compared to surrounding conservative cultures.

These women are not secluded, do not observe purdah, and actively participate in social, economic, and religious life. Men and women dance together in festivals, work together in fields, and interact freely in public spaces.

However, gender roles are clearly defined and respected.

Women’s Role in Daily Life

Kalash women are central to household management, agriculture, childcare, and cultural transmission. They work in fields, tend livestock, collect firewood, and manage food preparation.

Women are also custodians of tradition. Through songs, embroidery, storytelling, and rituals, they pass cultural knowledge to younger generations.

Despite external perceptions, these valleys women consider their lifestyle empowering rather than restrictive.

Men’s Role in Daily Life

Kalash men are responsible for herding livestock, farming, construction, trade, and protecting the community. They also play leading roles in religious rituals and festivals.

Men are expected to uphold honor, protect land, and maintain clan unity.

Both genders depend on each other for survival, creating a balanced social dynamic.

Purity, Gender, and the Bashali System

The Bashali is a key institution in Kalash social life. It is a separate house where women stay during menstruation and childbirth.

Contrary to outsider assumptions, the Bashali is not viewed negatively. It is considered a powerful, sacred space where women undergo important life transitions.

Women rest, socialize, and receive care from other women during this time. After childbirth, purification rituals are performed before reintegration into family life.

This practice reflects ancient beliefs about cosmic balance rather than social exclusion

Education and Cultural Tension

Formal education poses a dilemma for the Kalash. Schools often prioritize Islamic studies, creating pressure on Kalash children to assimilate.

Many parents fear that education may erode cultural identity, while others see it as essential for survival in the modern world.

NGOs and activists advocate for optional religious studies, Kalasha-language materials, and culturally sensitive curricula.

Daily Economic Life

The Kalash economy is primarily agro-pastoral. Families grow maize, wheat, fruits, and vegetables while raising goats and cattle.

Tourism has become an important income source, bringing both opportunity and risk. While it generates revenue, insensitive tourism threatens cultural integrity and sacred spaces.

Crafts, embroidery, and traditional jewellery are also sources of income, especially for women.

Community Solidarity and Conflict Resolution

Disputes are resolved through mediation rather than punishment. Clan elders and respected figures negotiate solutions, emphasizing harmony over blame.

This system has helped the Kalash survive centuries of external pressure without internal collapse.

Marginalization and Social Pressure

Despite their resilience, the Kalash remain marginalized. Their population declined from 10,000 in 1951 to around 3,700 in 2010.

Threats, forced conversions, land disputes, and economic vulnerability continue to push families into silence or migration.

As one Kalash resident said, “We don’t want to leave this land, but we are afraid.”

A Society Built on Balance

Kalash social life is built on balance—between men and women, humans and nature, tradition and survival. Every role, ritual, and relationship serves the larger goal of preserving identity.

Their social system is not frozen in time but adapting carefully, negotiating modernity without surrendering essence.

Kalash Traditional Clothes, Jewellery, Colors, Symbols and Visual Identity

The visual identity of the Kalash people is one of the most recognizable and powerful cultural markers in South Asia. Their clothing, jewellery, colors, and ornamentation are not merely aesthetic choices but living symbols of belief, history, gender roles, and spiritual worldview. In a region dominated by Islamic dress codes and subdued color palettes, this society attire stands out as a bold declaration of identity and resistance to assimilation.

Kalash clothing has remained remarkably consistent over centuries, despite political upheavals, forced conversions, and modern pressures. Every thread, bead, and color carries meaning tied to mythology, nature, and communal memory.

Clothing as Identity and Resistance

For these valleys, clothing is inseparable from religion and ethnicity. Wearing traditional dress is not optional; it is a visible affirmation of belonging to the Kalash worldview. In a region where conversion often leads to abandonment of indigenous customs, traditional clothing has become a boundary marker between Kalash and non-Kalash populations.

These Valley elders often say that as long as their people wear their traditional dress, their culture survives.

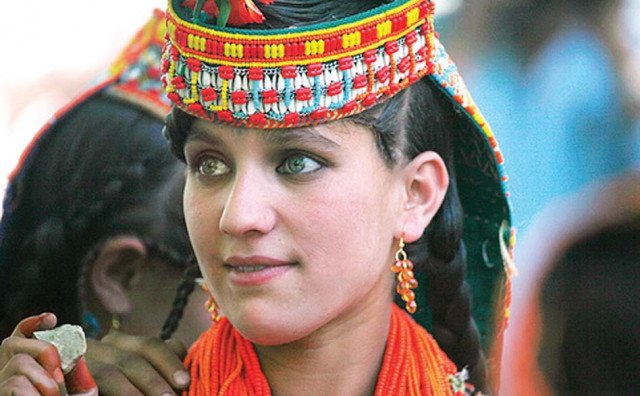

Women’s Traditional Dress of the Kalash

Kalash women are instantly recognizable by their distinctive black garments, which have earned them the local name “Black Kafirs” in Chitral. The women’s dress is called a long black robe, worn loose and flowing, covering the body from shoulders to ankles.

The black color does not symbolize mourning. Instead, it represents fertility, earth, and the cosmic balance between light and darkness in Kalash belief. Black provides a canvas upon which colorful embroidery and ornaments are displayed.

The dress is hand-stitched and often passed down generations. Girls begin wearing adult-style clothing from the age of four or five, reinforcing cultural continuity from early childhood.

Embroidery and Symbolism

Kalash women decorate their dresses with intricate embroidery along the neckline, sleeves, and hem. These patterns often include geometric shapes, floral motifs, and symbolic lines that represent mountains, rivers, fertility, and ancestral spirits.

Embroidery is not merely decorative. It is a language. Certain patterns indicate marital status, clan affiliation, or participation in festivals.

Women learn embroidery from mothers and grandmothers, making it a key method of transmitting cultural knowledge.

Headgear of Kalash Women

One of the most iconic elements of Kalash dress is the elaborate headpiece known as the traditional Kalash cap. This headdress is heavily decorated with beads, cowrie shells, buttons, coins, and colorful threads.

Cowrie shells are particularly important. Historically associated with fertility, wealth, and protection from evil spirits, cowries connect Kalash women to ancient trade routes and pre-Islamic belief systems.

The headdress often extends down the back, forming a cascade of ornaments that move as women walk or dance during festivals.

Different styles of headgear may be worn daily versus during festivals, with ceremonial versions being far more elaborate.

Jewellery of Kalash Women

Jewellery plays a central role in Kalash female identity. Kalash women wear multiple necklaces, sometimes layering dozens of strands across the chest.

These necklaces are made of beads, shells, seeds, and metal ornaments. Bright colors such as red, orange, blue, green, and yellow dominate, symbolizing life, harvest, fire, and the sun.

Bracelets, earrings, anklets, and hair ornaments are also common. Jewellery is often handmade and exchanged during marriages, festivals, and rites of passage.

Unlike modern jewellery, Kalash ornaments are not meant to be subtle. They are bold, loud, and celebratory, reflecting the these valleys worldview that life itself is meant to be visibly honored.

Men’s Traditional Clothing

Kalash men traditionally wore garments distinct from neighboring Muslim populations. However, over time, many men have adopted the Pakistani shalwar kameez for daily use due to practicality and external influence.

Despite this, traditional elements remain visible during festivals and rituals. Men often wear woolen garments, waistcoats, and caps specific to the region.

Headgear remains important for men, symbolizing adulthood and social responsibility.

Children wear miniature versions of adult clothing from an early age, reinforcing identity continuity.

Children’s Clothing and Cultural Training

Kalash children begin wearing traditional dress early in life. This early adoption is intentional. Clothing teaches children who they are before language fully forms identity.

Young girls wear simpler black dresses with minimal embroidery, while boys wear basic garments suited to physical activity.

As children grow, their clothing becomes more elaborate, marking their transition into adulthood.

Colors and Their Meanings

Kalash culture uses color symbolically rather than randomly.

Black represents earth, fertility, and continuity

Red symbolizes blood, life force, and sacrifice

White signifies purity in ritual contexts

Green represents nature, crops, and renewal

Yellow and orange are linked to the sun and divine energy

These colors appear repeatedly in clothing, jewellery, festival decorations, and ritual objects.

Clothing During Festivals

Festivals are when Kalash visual culture reaches its peak. Women wear their most ornate dresses and headdresses, often adding extra layers of jewellery.

Men also dress more traditionally during festivals, emphasizing ancestral continuity.

During festivals such as Chilam Joshi, Uchal, and Chowmos, clothing becomes a form of prayer. Dancing, movement, and sound activate the garments, making them part of the ritual itself.

Visitors often describe the festivals as overwhelming in color and motion, with black garments serving as a dramatic backdrop to vibrant ornaments.

Clothing and Kalash Beauty

Kalash beauty is often misunderstood or exoticized. The beauty of Kalash women lies not in Western standards but in confidence, cultural pride, and visible joy.

Kalash girls grow up seeing strong female figures openly expressing themselves through dress, dance, and voice. Beauty is not hidden or regulated by shame.

Facial features often described as “European” have led to myths about Greek ancestry, but genetics confirm ancient Indo-Aryan origins linked to Gandhara.

The perceived beauty of the Kalash is inseparable from their cultural expression.

Jewellery as Economic and Cultural Asset

Jewellery also serves as economic security. Women may sell or exchange jewellery in times of hardship.

Tourism has increased demand for Kalash-style ornaments, though elders caution against mass commercialization that strips items of cultural meaning.

Some NGOs support ethical craft initiatives to help Kalash women earn income without cultural exploitation.

Clothing, Conversion, and Identity Loss

When Kalash individuals convert to Islam, one of the first visible changes is abandonment of traditional clothing. This loss is deeply symbolic.

Converted villages, known as Sheikhanandeh, often retain language and some customs but not traditional dress, marking a clear cultural boundary.

For this reason, elders emphasize clothing preservation as cultural survival.

Modern Challenges to Traditional Dress

Modern influences pose challenges. Younger generations face pressure from schools, media, and surrounding societies to conform.

Traditional garments are time-consuming to produce and not always practical for modern work environments.

However, festivals and communal expectations ensure that traditional clothing remains alive.

Why Kalash Clothing Matters Globally

Kalash attire represents one of the last surviving expressions of pre-Islamic Indo-Aryan culture in South Asia.

It is a living archive of ancient belief systems, trade histories, and artistic expression.

Preserving Kalash clothing is not only about aesthetics; it is about protecting a worldview that values balance between humans, nature, and the divine.

Visual Identity as Survival

In a world that pressures minorities to blend in, the Kalash continue to stand out deliberately. Their clothing is a statement: they exist, they remember, and they refuse to disappear quietly.

As long as Kalash women wear their black robes and layered jewellery, their ancestors walk with them.

Kalash Beauty, Kalash Girls, Identity, Myths, Representation and Reality

The concept of beauty among the Kalash people cannot be separated from culture, religion, clothing, freedom, and collective identity. Kalash beauty is not a static physical standard but a lived expression shaped by confidence, movement, color, ritual, and belonging. Over time, Kalash women and girls have been romanticized, exoticized, misunderstood, and sometimes reduced to myths, particularly by tourists, media, and foreign narratives.

Understanding Kalash Beauty Beyond Stereotypes

Kalash beauty is often framed externally through physical traits such as lighter skin, colored eyes, and facial features that outsiders associate with European ancestry. These perceptions have fueled long-standing myths linking the Kalash to Alexander the Great. However, for the Kalash themselves, beauty is not about ancestry myths or foreign comparisons.

Beauty is seen as vitality, joy, openness, and harmony with nature and the divine. A woman dancing freely during a festival, adorned in traditional dress and jewellery, represents beauty in its fullest cultural sense.

Kalash elders often emphasize that beauty lies in living according to tradition, honoring the gods, and participating fully in communal life.

Kalash Girls and Early Socialization

Kalash girls grow up in a markedly different social environment compared to surrounding societies. From early childhood, girls are visible members of public life. They accompany mothers to fields, festivals, rituals, and community gatherings.

Girls wear traditional dress from the age of four or five, signaling early inclusion into cultural identity. They learn songs, dances, and rituals through participation rather than formal instruction.

This early exposure creates confidence and a strong sense of belonging. Kalash girls are not taught to hide themselves; they are taught to express themselves.

Freedom and Social Interaction

One of the most distinctive aspects of Kalash society is the relative freedom of interaction between males and females. Unlike neighboring communities, Kalash culture does not enforce strict gender segregation.

Girls and boys interact openly during daily activities and festivals. This openness is rooted in religious belief rather than modern ideology. The Kalash worldview sees interaction as part of cosmic balance rather than moral danger.

This does not mean absence of social norms. Behavior is governed by community expectations, ritual purity rules, and respect for elders.

Beauty and Clothing as Expression

Traditional clothing plays a central role in shaping Kalash beauty. The black dress, layered jewellery, and ornate headpieces are not designed to conceal but to celebrate the body in motion.

During dances, jewellery moves rhythmically, reflecting sunlight and firelight, enhancing the visual power of performance. Beauty is dynamic, not static.

Kalash girls learn to carry themselves with pride, knowing their appearance is a reflection of their culture.

Kalash Girls and Education

Despite cultural strengths, Kalash girls face significant challenges in education. As documented in Chitral’s education statistics, the lack of post-primary schools, especially for girls, leads to high dropout rates after class five.

Families often prioritize boys’ education due to economic constraints. Girls remain engaged in household labor, farming, and caregiving.

This creates a tension between cultural freedom and structural limitation. While Kalash girls enjoy social openness, they face restricted access to formal opportunities.

Transition to Womanhood

The transition from girlhood to womanhood in Kalash society occurs early. Girls are initiated into womanhood around the age of four or five symbolically, and marriages can occur in the early teenage years.

This early transition is deeply embedded in tradition but raises concerns regarding wellbeing, education, and health in modern contexts.

Despite this, Kalash women retain agency in marital matters that is rare in surrounding cultures.

Marriage and Female Choice

Kalash women have the right to choose their partners and to leave marriages. Wife elopement is recognized as a legitimate custom and is considered one of the great traditions of the Kalash.

If a woman chooses a new husband, the new husband must compensate the former husband with double the bride price. This system, while controversial externally, reinforces female agency within the cultural framework.

Marriage is not viewed as ownership but as a social contract subject to choice.

Beauty and Dance in Festivals

Dance is one of the most powerful expressions of Kalash beauty. During festivals such as Chilam Joshi, Uchal, and Chowmos, women and girls dance collectively in circular formations.

Dance is both aesthetic and religious. It is believed to please the gods and maintain cosmic balance.

These Valleys girls learn dances by observing elders, participating gradually until they become confident performers.

The beauty of dance lies in unity rather than individual display.

The Role of Music

Music enhances beauty by connecting movement to myth. Traditional drums, flutes, and chants guide dancers.

Music is believed to bridge the human and spiritual worlds. When Kalash girls dance, they are not performing for spectators but participating in sacred rhythm.

This spiritual dimension is often misunderstood by tourists who view dances as entertainment.

Myths About Kalash Beauty

One of the most persistent myths is the idea that Kalash women are direct descendants of Greeks and therefore “European” in beauty.

Genetic research and archaeological evidence suggest Indo-Aryan ancestry linked to ancient Gandhara, not Greek soldiers.

The Greek myth has often overshadowed the Kalash’s indigenous identity, reducing them to curiosities rather than a living culture.

Another myth is that Kalash women are “free” in a modern Western sense. In reality, their freedom exists within cultural boundaries shaped by religion and tradition.

Tourism and Exoticization

Tourism has amplified the visibility of these valleys women, sometimes in harmful ways. Cameras, intrusive behavior, and objectification have become major concerns.

Women have expressed discomfort with tourists photographing them without consent, particularly during rituals.

Kalash elders and women leaders increasingly advocate for ethical tourism that respects privacy and cultural norms.

Beauty should not come at the cost of dignity.

Media Representation

Media portrayals often focus on appearance rather than lived realities. Headlines emphasize “pagan girls,” “lost tribes,” or “ancient beauties,” reinforcing stereotypes.

These narratives ignore issues such as education gaps, land rights, and cultural erosion.

Some Kalash activists and scholars are working to reclaim their narrative through museums, publications, and community-led documentation.

Kalash Beauty and Modern Pressure

Modernization brings conflicting pressures. Social media introduces new beauty standards that can clash with traditional values.

Some young Kalash girls feel torn between traditional identity and modern aspirations.

However, festivals, rituals, and communal expectations continue to anchor identity.

Health and Wellbeing of Kalash Women

Despite visible cultural vitality, Kalash women face health challenges. Limited healthcare access, early marriage, and childbirth practices affect wellbeing.

The bashali system, which requires women to live separately during menstruation and childbirth, is culturally significant but raises health concerns.

Women themselves actively discuss these issues within the community, showing agency and awareness.

Marginalization and Resilience

Kalash women belong to one of Pakistan’s most marginalized ethno-religious minorities. They face discrimination, conversion pressures, and legal invisibility.

Despite this, they maintain resilience through community bonds, ritual participation, and cultural pride.

Beauty, in this context, becomes an act of resistance.

Kalash Girls and the Future

The future of Kalash beauty lies in education, economic empowerment, and cultural preservation.

Teaching Kalasha language and culture in schools is crucial for sustaining identity.

Empowering girls does not mean abandoning tradition but strengthening it through informed choice.

Beauty as Cultural Survival

Kalash beauty is not cosmetic. It is cultural survival made visible.

When these girls wear traditional dress, dance during festivals, and speak their language, they embody continuity across millennia.

Their beauty tells a story older than borders, empires, and modern states.

Why Kalash Beauty Matters

Kalash beauty challenges dominant narratives about modernity, religion, and gender.

It shows that joy, color, and openness can coexist with tradition.

In a world that often silences indigenous voices, Kalash women continue to speak through movement, color, and song.

As long as Kalash girls dance under the mountain sky, their culture remains alive.

Kalash Festivals – Chilam Joshi, Uchal, Chowmos, Phoo and the Sacred Calendar

Festivals are the heart of Kalash life. Unlike societies where festivals are occasional breaks from routine, for the Kalash people festivals are the primary way religion, history, social order, agriculture, and identity are practiced and preserved. The Kalash calendar is dense with celebrations, rituals, sacrifices, and communal feasts. Through festivals, they communicate with their gods, mark seasonal change, reinforce social bonds, and transmit culture to the next generation.

These festivals are not performances for outsiders; they are sacred obligations. Music, dance, sacrifice, and celebration are acts of worship that maintain balance between humans, nature, and the divine.

The Festival-Centered Kalash Worldview

These Valleys do not follow daily prayer routines like monotheistic religions. Instead, religious devotion is concentrated in festivals. This structure makes festivals central to spiritual life.

There are more than thirty community-level festivals throughout the year, alongside dozens of clan, family, and ritual events related to birth, marriage, death, purification, and agriculture.

The most important festivals are Chilam Joshi, Uchal, Phoo, and Chowmos. Each festival corresponds to seasonal cycles and agricultural milestones.

Sacred Time and the Kalash Calendar

Kalash time is cyclical rather than linear. Seasons repeat, rituals return, and ancestral patterns guide the present.

Festivals are timed according to solar cycles, agricultural needs, and mythological beliefs. Each festival has fixed dates and ritual sequences that must be followed precisely.

Failure to perform rituals correctly is believed to disturb cosmic balance and anger the gods.

Chilam Joshi – The Spring and Fertility Festival

Chilam Joshi, also known as Joshi or Chilimjusht, is celebrated in mid-May and marks the arrival of spring. It is one of the most colorful and joyful Kalash festivals.

This festival celebrates fertility, renewal, and abundance. It marks the movement of livestock to high pastures and the awakening of the land after winter.

Ritual Significance of Chilam Joshi

Chilam Joshi honors gods associated with fertility, livestock, and growth. Milk plays a central role, symbolizing purity and nourishment.

Before the festival, milk is collected and stored. During rituals, it is offered to gods and sprinkled in sacred spaces.

Purification rituals are performed to cleanse individuals and the community.

Music and Dance in Chilam Joshi

Dance during Chilam Joshi is vibrant and communal. Men and women form circles, moving rhythmically to drumbeats.

Kalash girls wear their finest embroidered dresses and layered jewellery. Flowers are woven into headpieces, enhancing the spring symbolism.

Dance is both prayer and celebration. Movements are repetitive, reinforcing unity and continuity.

Social Dimensions of Chilam Joshi

Chilam Joshi is also a time of social interaction. Young men and women meet openly, and relationships often begin during this festival.

Marriage proposals and elopements sometimes follow Chilam Joshi.

The festival reinforces social bonds and renews communal identity.

Uchal – The Harvest and Gratitude Festival

Uchal is celebrated in August and marks the completion of summer harvests. It is a festival of thanksgiving.

The community expresses gratitude to gods for crops, fruits, and livestock.

Wheat, maize, grapes, walnuts, and apricots form the core of ritual offerings.

Agricultural Importance of Uchal

Kalash livelihoods are deeply tied to agriculture and animal husbandry. Uchal acknowledges this dependence.

Fields, storage areas, and livestock are ritually purified.

Food prepared during Uchal uses freshly harvested ingredients, reinforcing the link between land and ritual.

Uchal Celebrations and Communal Feasts

Communal feasting is central to Uchal. Families contribute food, and meals are shared openly.

Music and dance accompany feasts, but the mood is calmer than Chilam Joshi.

Elders lead prayers and sacrifices at altars.

Phoo – The Autumn Festival

Phoo is a lesser-known but significant festival celebrated in mid-autumn. It marks the transition from active agricultural work to preparation for winter. Phoo involves rituals related to livestock, household purification, and protection against illness.

The festival emphasizes balance and restraint rather than exuberance.

Chowmos – The Winter Solstice and New Year Festival

Chowmos is the most sacred and complex of all Kalash festivals. Celebrated from early to late December, it marks the winter solstice and the Kalash New Year.

Chowmos celebrates the rebirth of the sun and the renewal of cosmic order.

It is a time of intense ritual activity, purification, and myth reenactment.

Cosmic Beliefs in Chowmos

Kalash believe that on December 21, a new sun is born. This moment affects all life.

Chowmos rituals ensure the safe transition from old to new cosmic cycles.

Darkness and light, purity and impurity, old and new are central themes.

Purification Rituals During Chowmos

Purification is crucial during Chowmos. Certain individuals, particularly those considered ritually impure, must undergo cleansing rituals.

Men and women observe specific rules regarding movement, food, and contact.

Fire plays a key role in purification.

Masked Dances and Mythic Performance

Chowmos features masked dances representing spirits, ancestors, and mythological beings.

These dances are believed to invite divine presence into the community.

Songs performed during Chowmos recount ancient myths and moral lessons.

Role of Shamans and Qazis

Betaan, or shamans, play a vital role during Chowmos. They communicate with spirits, interpret signs, and guide rituals.

Qazis oversee social order and resolve disputes during festival gatherings.

Gender Roles in Festivals

Women are central to festival preparation and performance. They prepare food, dress ritual spaces, and lead dances.

Despite ritual purity rules, women’s presence is essential to divine pleasure.

These women actively participate in discussions about festival practices and tourism.

Festivals and Tourism

Kalash festivals attract domestic and international tourists. While tourism provides income, it also poses risks.

Insensitive behavior, photography, and commercialization threaten ritual integrity.

Kalash leaders increasingly advocate for controlled, community-led tourism.

Disappearing Rituals

Several festivals and rituals have disappeared due to economic pressures and generational change.

Gandao, Dur Neweshi, Sariyak, Dewaka, Basun Marat, Kish Saraz, Istom Saraz, and Kirik Pushik are no longer widely practiced.

Loss of these rituals represents erosion of intangible heritage.

Festivals as Cultural Resistance

In the face of conversion pressures and modernization, festivals act as resistance.

By continuing rituals, the Kalash assert identity and survival.

Each festival becomes a declaration of existence.

Interfaith Harmony During Festivals

Despite threats, Kalash festivals often occur peacefully with support from neighboring Muslim communities.

Interfaith harmony has helped protect festivals from disruption.

This coexistence is often overlooked in media narratives.

Festivals and Youth

Youth participation is essential for continuity. Elders encourage children to dance, sing, and observe rituals.

Teaching through participation ensures survival of tradition.

Why Kalash Festivals Matter?

Kalash festivals are living archives. They preserve language, music, myth, and social values.

They represent one of the world’s oldest continuous ritual systems.

Losing them would mean losing a unique human worldview.

Festivals as the Soul of Kalash Culture

Without festivals, Kalash religion would fade. Festivals bind people to land, ancestors, and gods.

They transform hardship into celebration and fear into unity.

As long as drums echo in the valleys, Kalash culture endures.

Kalash Religion, Gods, Mythology, Spirits, and Sacred Beliefs

The Kalash people are often described as one of the most unique religious communities in Pakistan. Their faith, commonly referred to as Kalasha religion, is a form of animism, polytheism, and ancestor worship. Academics have also described it as a surviving form of ancient Hinduism. Unlike monotheistic religions, Kalash religion does not revolve around scripture or formalized dogma but instead centers on ritual, seasonal festivals, mythology, and a continuous interaction between humans, spirits, and gods.

Polytheistic Beliefs of the Kalash

The Kalash worship a pantheon of twelve gods and goddesses, with Mahandeo considered the chief deity. Each god has a specific role in maintaining harmony between the human world, nature, and the cosmos. Festivals, music, and dance are essential in pleasing these deities, maintaining spiritual balance, and ensuring prosperity. Kalash mythology links every human action to the universe, showing how the divine flows through daily life.

Ancestral Worship and Spiritual Lineage

Ancestor worship is central to Kalash spirituality. They believe that spirits of deceased ancestors influence the living and the environment. Offerings, prayers, and sacrifices are ways to honor these ancestors and gain guidance for the community. This veneration ensures continuity of family lineage, social cohesion, and moral order. In villages, altars dedicated to ancestors are common, where rituals are performed to maintain their favor.

Betaan: The Shaman and Mediator

The Betaan, or shaman, is a key religious figure. He interprets divine will, makes prophecies, and communicates with spirits and fairies. Betaan leads major religious rituals during festivals, including sacrifices and purification ceremonies. He also plays a social role, advising on community disputes and resolving tensions. His guidance ensures that religious observances align with both cosmic expectations and practical life.

Sacred Spaces and Altars

Kalash villages have multiple sacred spaces, each dedicated to specific gods or spirits. Altars are typically made from stone or wood and are situated at high points in the village or near forests, rivers, or springs. Offerings such as milk, grains, and symbolic items are presented at these altars. Altars are especially active during major festivals like Chilam Joshi, Uchal, Phoo, and Chowmos.

Ritual Purity and Women’s Sacred Roles

Ritual purity is crucial in Kalash religion. Women play a unique role in sacred practices, especially during menstruation and childbirth. They live in a Bashali, a secluded building outside the main settlement, until they regain purity. Birth and postpartum rituals are performed here, ensuring spiritual and physical cleanliness. The husband actively participates in restoration rituals after childbirth, reflecting the interconnectedness of family and religion.

Cosmology and Mythology

Kalash cosmology is rich and symbolic. They believe in a continuous interaction between the human soul, the universe, and divine beings. The movement of the sun, phases of the moon, and seasonal changes are seen as manifestations of divine will. For example, the birth of a “new sun” on December 21, celebrated during Chowmos, is considered a pivotal event affecting flora, fauna, and human fortune.

Mythical stories, often transmitted orally, narrate the origins of gods, spirits, and humans. These epics explain social order, agricultural cycles, and moral behavior. Through music and dance, myths are enacted during festivals, allowing to experience spiritual truths and preserve cultural memory.

Nature Spirits and Fairies

The Kalash acknowledge the presence of spirits in nature, including mountains, rivers, forests, and fields. Fairies are believed to inhabit these natural spaces and play roles in blessing or cursing individuals and crops. Offerings and prayers to these spirits are frequent, and shamans often act as intermediaries. This belief system strengthens their connection to their environment and reinforces conservation practices.

Sacrificial Practices

Sacrifices are central to maintaining divine favor. Livestock, especially goats and chickens, are commonly offered during festivals and important life events. Sacrifices are symbolic acts that reinforce reciprocity between humans and gods. The ritual slaughter is accompanied by prayers, music, and dance, demonstrating that sacrifice is both religious and communal.

Festivals as Sacred Rituals

The connection between festivals and religion is inseparable. Each festival represents a cosmic or agricultural event. Chilam Joshi celebrates fertility and spring; Uchal gives thanks for the harvest; Phoo marks seasonal transition; Chowmos celebrates the winter solstice and the rebirth of the sun. Every festival is carefully observed with ritual dances, music, offerings, and prayers.

Marriage and Religious Beliefs

Marriage in Kalash religion is both a social and spiritual contract. Rituals performed before, during, and after marriage involve gods, ancestors, and shamans. Women have freedom in selecting partners, but rituals must be observed to ensure blessings. Elopements and bride-price customs are closely tied to maintaining spiritual and social balance. The new husband must pay double if a woman leaves her former husband, reinforcing moral and ritual accountability.

Death and Mourning Practices

Mourning rituals also reflect religious beliefs. When someone dies, the family and community perform ceremonies to honor ancestors and ensure the deceased’s spirit joins the ancestral realm. Music, prayers, and ritual cleansing are part of these practices. Special attention is given to female relatives, whose purity and spiritual state are closely managed according to tradition.

Spiritual Education and Oral Tradition

Kalash religion is taught primarily through observation and participation rather than written texts. Children learn myths, rituals, and ethical codes by participating in festivals, observing rituals, and listening to elders and shamans. Oral transmission ensures adaptability and resilience while preserving authenticity. Songs, dances, and storytelling reinforce spiritual lessons, historical memory, and social norms.

Religious Challenges and Conversion Pressures

The Kalash have faced pressure to abandon their religion, often receiving threats from local religious extremists. These pressures have accelerated demographic decline and forced some families to migrate or hide their beliefs. Despite government protection and local administration efforts, many Kalash feel insecure. Festivals, rituals, and public adherence to religious practices have become acts of resistance and cultural preservation.

Religious Tourism

Kalash religion attracts foreign interest, particularly from anthropologists, conservationists, and tourists. Greek-funded NGOs, for instance, support the preservation of temples, altars, and rituals. While tourism provides financial incentives, it also risks commercialization and disruption of sacred practices. The Kalash have responded by regulating tourist access and emphasizing respectful observation of festivals and rituals.

Religious Symbols in Daily Life

Kalash religious beliefs permeate everyday life. Clothing, jewelry, household arrangements, and even fieldwork are informed by ritual norms. Women’s cowrie-embroidered dresses symbolize divine protection, while headpieces decorated with flowers reflect seasonal celebrations and spiritual joy. Men wear shalwar kameez for daily life but don ceremonial attire for festivals, demonstrating respect for tradition and the sacred calendar.

Kalash Religion and Social Cohesion

Religion is the binding force in Kalash society. Shared worship, festival participation, and adherence to ritual norms create solidarity and identity. Even converts to Islam maintain aspects of these valleys culture, showing the resilience of indigenous religious practice. Shamans, elders, and community leaders guide the society in balancing tradition and contemporary challenges.

Kalash Clothing, Jewellery, Symbols, and Craftsmanship.

The clothing and jewellery of the Kalash people are more than mere attire—they are living expressions of their culture, spirituality, and identity. Every dress, every ornament, and every pattern has symbolic meaning, connecting the wearer to the ancestral traditions, festivals, and religious practices of these valleys. They are renowned not only for their distinctive style but also for their use of clothing and adornments to express social roles, spiritual beliefs, and communal belonging.

Traditional Clothing of Kalash Women

Kalash women’s clothing is immediately recognizable due to its vibrant colors, intricate embroidery, and cowrie shell decorations. Women typically wear long black robes, often embroidered with multicolored threads and adorned with cowrie shells, beads, and coins. These embellishments serve multiple purposes: they symbolize protection from evil spirits, showcase artistic skill, and indicate social and marital status. Women also wear beautifully decorated headdresses, often covered with flowers during festivals. The cowrie shells have spiritual significance in Kalash religion, acting as charms to attract divine favor and prosperity.

Girls begin wearing adult-style clothing at the age of four, marking a cultural milestone in their social development. From this age, they learn the intricacies of embroidery and costume preparation, skills that connect them to their heritage. Daily wear for women is practical but retains its cultural motifs, whereas festival attire is highly elaborate, featuring additional layers, bright colors, and ornamental accessories.

Men’s Clothing

Kalash men have largely adopted the Pakistani shalwar kameez for everyday wear, reflecting cultural adaptation and interaction with neighboring communities. However, during festivals, ceremonies, and religious rituals, men wear traditional garments that highlight their cultural heritage. These ceremonial attires often include decorative sashes, embellished caps, and colorful waistcoats, emphasizing status and respect for tradition. Men’s clothing, though less ornate than women’s, remains an essential marker of identity within the community.

Children’s Attire

Kalash children’s clothing mirrors adult attire, ensuring early immersion into the cultural and social fabric of the community. Boys and girls wear miniature versions of adult outfits, complete with embroidery, shells, and symbolic ornaments. The early adoption of traditional clothing helps children internalize community values, festival customs, and religious rituals from a young age.

Kalash Jewellery: Symbolism and Craftsmanship

Jewellery is a vital component of Kalash identity. Women, in particular, wear elaborate necklaces, earrings, bracelets, and headdresses. Cowrie shells, beads, stones, and metals are the primary materials, each carrying symbolic meanings of wealth, protection, fertility, and spiritual alignment. Headdresses and floral crowns are especially prominent during festivals, marking the wearer’s participation in sacred rituals and seasonal celebrations.

Jewellery is also tied to social and marital status. Married women may wear specific patterns or ornaments that denote their role in the household, while unmarried girls wear pieces that signify youth and eligibility. Jewelry is handcrafted using traditional techniques passed down through generations, combining aesthetic appeal with cultural symbolism.

Craftsmanship and Artisanal Skills

Kalash clothing and jewellery reflect sophisticated artisanal craftsmanship. Embroidery, weaving, beadwork, and shell adornment require precise skill, patience, and deep knowledge of cultural motifs. Many designs are inspired by nature—flowers, trees, rivers, and mountains—and carry spiritual meanings linked to Kalash religious beliefs. For example, certain patterns are used to invoke blessings from ancestors or protect the wearer from malevolent spirits.

Women are primarily responsible for creating these garments and ornaments. They learn from mothers and grandmothers, preserving the techniques and motifs unique to their lineage. The process is labor-intensive but highly valued, with completed garments and jewellery regarded as treasures within families and the community.

Clothing and Festivals

Kalash festivals provide an opportunity to display the full range of traditional attire and ornaments. During Chilam Joshi, women wear vibrant robes with fresh flowers in their headdresses, while men don colorful ceremonial attire. During Uchal, Phoo, and Chowmos, clothing is combined with music, dance, and ritualistic movements, integrating visual beauty with spiritual meaning. Festival clothing is not only decorative but serves as an offering to the gods, expressing devotion, joy, and gratitude.

Seasonal and Practical Adaptations

While festival clothing is ornate, everyday clothing is adapted to the mountainous terrain and climate of the Kalash valleys. Woolen garments, layered robes, and durable fabrics protect against harsh winters and enable agricultural work. Despite practical considerations, even daily wear maintains traditional embroidery and shellwork, ensuring that Kalash identity is visible year-round.

Special Clothing Rituals

Certain clothing items are linked to life events, such as puberty, marriage, and childbirth. Girls entering womanhood at four or five are given specific garments that signify their transition. Married women receive additional ornaments and embroidered robes, reflecting their new responsibilities and social role. Clothing thus functions as a symbolic language, communicating personal milestones, social status, and spiritual alignment.

Kalash Jewellery in Rituals and Daily Life

Jewellery is inseparable from religious and social practices. Women wear necklaces, bracelets, and headdresses during daily prayers, seasonal festivals, and life rituals. The Betaan often instructs the type and placement of jewelry during sacred ceremonies. Cowrie shells, beads, and ornamental stones are strategically arranged to enhance spiritual efficacy, whether in invoking protection, fertility, or guidance from ancestors.

Men, though less adorned, wear symbolic items such as sashes and ceremonial caps during rituals. Even children wear miniature ornaments to signify cultural education and integration into communal religious life.

Influence of Religion on Clothing and Jewellery

Kalash clothing and jewellery are deeply influenced by religious beliefs. Colors, patterns, and ornaments are not randomly chosen but are carefully designed to reflect spiritual cosmology. Red, black, and green, for example, may symbolize life, protection, and prosperity. Shells, beads, and floral crowns serve as metaphysical tools in invoking divine favor and maintaining spiritual balance. The integration of religion into visual and material culture ensures that identity, faith, and aesthetics are inseparable.

Cultural Continuity Through Attire

Clothing and jewellery preserve cultural memory and transmit knowledge across generations. Despite external pressures from modernization, tourism, and religious conversion attempts, traditional Kalash attire continues to flourish, particularly in villages such as Bamboret, Rumbur, and Birir. Women’s embroidery, men’s ceremonial clothing, and children’s miniature garments maintain continuity with ancestral practices, reinforcing social cohesion and resilience.

Tourism and Preservation of Traditional Attire

Tourism in the these valleys has highlighted the beauty and uniqueness of Kalash clothing and jewellery. Visitors are drawn to festivals where traditional attire is showcased, providing opportunities for cultural preservation and economic benefit. NGOs and conservationists also emphasize the importance of maintaining authentic designs and handicrafts, ensuring that commercialization does not dilute cultural integrity.

Clothing and Jewellery as Identity Markers

Kalash attire functions as a clear identity marker within the broader region. While neighboring communities may wear more homogenized Pakistani clothing, Kalash garments and ornaments immediately signal ethno-religious identity. This visual distinction is critical in maintaining social boundaries, preserving language, and reinforcing cultural pride.

Symbolism of Embroidery and Motifs

Embroidery is not merely decorative; each motif carries symbolic meaning. Geometric shapes, floral designs, and cosmic patterns communicate spiritual beliefs, seasonal cycles, and moral lessons. These motifs are integrated into dresses, headdresses, and ceremonial sashes, connecting the wearer to ancestors, gods, and nature. Mastery of embroidery is thus both an artistic achievement and a form of spiritual literacy.

Jewellery Making as a Community Skill

Jewellery making is a communal and intergenerational activity. Women gather to share techniques, trade materials, and collectively produce intricate ornaments. This process reinforces social bonds, transmits cultural knowledge, and ensures that craftsmanship skills survive despite the pressures of modernization and migration.

Headdresses and Festival Crowns

Headdresses are particularly significant during festivals. Women decorate them with flowers, shells, and coins, symbolizing fertility, prosperity, and divine favor. Crowns worn during festivals such as Chilam Joshi or Chowmos are both decorative and sacred, emphasizing the wearer’s participation in communal worship and spiritual celebration.

Clothing and Social Messages

Kalash attire communicates social information, including marital status, age, and family lineage. Married women wear distinctive robes and ornaments, while unmarried girls display simpler attire. Festival dress elevates social visibility and reinforces adherence to communal norms. The deliberate use of clothing and jewellery as a social language ensures cohesion, moral order, and cultural continuity.

Challenges to Traditional Clothing

Despite its importance, traditional Kalash attire faces challenges. Economic pressures, modern fashion trends, and the migration of families to urban areas threaten to dilute authentic designs. Additionally, the influx of tourists sometimes encourages modifications to meet commercial demands. Nonetheless, community elders, women artisans, and NGOs actively work to preserve the integrity of Kalash clothing and jewellery, recognizing its central role in cultural survival.

Kalash Festivals, Music, Dance, and Special Rituals

The Kalash people are widely celebrated for their vibrant festivals, lively music, and traditional dances, which together form the heartbeat of their cultural and spiritual life. Festivals are not merely social events; they are deeply embedded in Kalash cosmology, agricultural cycles, and religious beliefs. Through festivals, these valleys celebrate the universe, honor their gods and ancestors, and reaffirm their communal identity. Music, dance, and ritual are inseparable from these events, each element carefully choreographed to align with spiritual traditions and social cohesion.

Major Kalash Festivals

The Kalash calendar is punctuated by four major festivals, each associated with seasonal changes, agricultural milestones, and religious observances. These festivals—Chilam Joshi (Joshi), Uchal, Phoo, and Chowmos—combine worship, music, dance, food, and community participation.

Chilam Joshi (Joshi Festival)

Chilam Joshi, celebrated in May, marks the arrival of spring and the fertility of the land. It is a time for blessing crops, livestock, and the community. Villagers adorn themselves in their most elaborate traditional clothing, with women wearing embroidered black robes, cowrie shell decorations, and floral crowns. Men wear ceremonial sashes, caps, and decorative waistcoats.

Music and dance are central to Chilam Joshi. Drums, flutes, and traditional string instruments accompany dancers in intricate, circular patterns symbolizing harmony with nature and the divine. The dances are not mere entertainment; they are believed to please the gods and ensure the prosperity of crops and livestock. Offerings of milk, grain, and traditional dishes are made on altars to honor the gods.

The festival also fosters social cohesion, with young people participating in courtship dances, often leading to marriages or proposals. Chilam Joshi, therefore, functions as a religious, social, and ecological celebration, deeply intertwining human life with the rhythms of nature.

Uchal Festival

The Uchal festival, celebrated in the summer, is closely connected to livestock and the pastoral life of the Kalash. This festival involves blessings for animals, ensuring fertility and health. Villagers gather to perform ritual dances, accompanied by traditional music, around decorated altars.

Women’s attire during Uchal includes vibrant headdresses with fresh flowers, layered robes, and decorative jewellery. Men’s ceremonial dress is similarly adorned with sashes and caps. The festival reinforces social bonds, as neighbors and distant relatives travel to participate, sharing food, music, and dance.

Phoo Festival

Phoo, celebrated in the autumn, is associated with the harvest and preparation for winter. During this festival, the Kalash offer thanks for the bounty of the land. Traditional dances, music, and feasting dominate the celebrations. Women prepare special Kalash dishes, using locally sourced grains, vegetables, and dairy products.

Music is performed using traditional flutes, drums, and string instruments. Dancers follow rhythmic patterns representing cosmic cycles and human-nature harmony. Phoo also serves as an educational event, where children learn the steps, songs, and stories associated with Kalash mythology. This transmission ensures that cultural knowledge passes to the next generation.

Chowmos Festival

Chowmos, celebrated in December, marks the winter solstice and the rebirth of the sun. It is the longest and most significant festival, lasting up to a week. The Kalash believe that the new sun influences the flora, fauna, and human prosperity of the valleys.

During Chowmos, men and women build temporary altars, offer sacrifices, and perform nightly dances. Women wear the most elaborate festival attire, decorated with beads, shells, and floral crowns. Men also wear ceremonial garments that signify spiritual devotion. Music is constant, with drumming, chanting, and singing maintaining the rhythm of rituals.

Special rituals during Chowmos include communal prayers, offerings to the twelve gods and goddesses, and blessings for children and livestock. The festival also involves storytelling, recounting myths of the Kalash gods, ancestors, and cosmology. Through these practices, Chowmos reinforces religious beliefs, communal identity, and intergenerational transmission of culture.

Music in Kalash Culture

Music is central to Kalash festivals and daily life. It is considered a sacred medium connecting humans with the divine. Traditional instruments include drums, flutes, and stringed instruments unique to the valleys. Musical patterns follow rhythms that mimic natural cycles, such as the growth of crops or the movement of celestial bodies.

Songs often recount the exploits of gods, ancestors, and legendary heroes. Lyrics may also include moral lessons or agricultural guidance, ensuring that knowledge and cultural values are shared alongside entertainment. Both men and women participate in music-making, with specific roles assigned according to age, gender, and ritual significance.

Dance as a Spiritual Practice

Kalash dance is not merely a form of artistic expression; it is a ritualistic activity that embodies spiritual beliefs. Dancers follow choreographed steps representing cosmic patterns, fertility cycles, and ancestral guidance. Dance is performed in communal spaces, around altars, or in fields, connecting participants to both the divine and the land.

Women’s dances often emphasize flowing movements, symbolizing fertility and renewal. Men’s dances may involve vigorous, rhythmic steps representing strength, protection, and communal unity. Children are introduced to these dances at a young age, learning both technique and the symbolic meaning behind each movement.

Role of Rituals in Festivals

Rituals are intertwined with Kalash festivals. Sacrifices, offerings, and prayers are performed under the guidance of the Betaan (shaman), who mediates between the human and divine realms. Rituals also include purification practices, such as seclusion during menstruation or childbirth, performed in the Bashali. These rituals maintain spiritual balance and social order, linking everyday life with sacred observances.

Certain rituals also involve astrology and astronomy. The Kalash track celestial movements, believing that stars and planets influence agriculture, health, and fortune. During festivals, rituals align with these celestial cycles, reinforcing the spiritual connection between humans, nature, and the cosmos.

Food and Festive Dishes

Food plays an integral role in Kalash festivals. Special dishes are prepared using local ingredients, including dairy, grains, and seasonal vegetables. Meals are shared communally, fostering social bonds and expressing gratitude to the gods. Traditional dishes are often tied to specific festivals, with recipes passed down through generations.

Offering food on altars is a common ritual, symbolizing devotion and reciprocity with the divine. The preparation and sharing of food also reinforce cultural identity, ensuring that culinary heritage remains vibrant alongside music, dance, and clothing traditions.

Kalash Weddings and Festival Connections

Kalash festivals are closely linked to marriage customs. Courtship dances, communal celebrations, and ritualized interactions during festivals create opportunities for young people to find partners. Elopement is a recognized custom, often facilitated during festivals when social gatherings allow discretion and negotiation between families. Weddings themselves incorporate music, dance, and traditional attire, reflecting the same cultural aesthetics celebrated during seasonal festivals.

Cultural Preservation through Festivals

Festivals are critical for preserving Kalash culture amid pressures from modernization, tourism, and religious conversion. Through communal participation in music, dance, rituals, and clothing, younger generations internalize cultural values. NGOs and conservationists also highlight festivals as opportunities to document and protect intangible cultural heritage, ensuring that Kalash identity remains visible and resilient.

Challenges to Festivals and Rituals

Despite their centrality, Kalash festivals face challenges. External threats, such as religious extremism, economic pressures, and migration, sometimes restrict participation. Tourism, while providing economic benefits, can lead to commercialization or misrepresentation of rituals. Nevertheless, community elders, religious leaders, and cultural activists actively safeguard festival practices, ensuring that authenticity is preserved.

The integration of spirituality, music, and dance exemplifies the holistic nature of Kalash culture. Festivals are not isolated events; they embody religious devotion, social cohesion, ecological awareness, and artistic expression. Through this integration, the Kalash maintain a living connection to their ancestors, gods, and natural environment.

Children’s Participation and Cultural Education

Children actively participate in festivals, learning dances, songs, and rituals from elders. This involvement ensures intergenerational transmission of knowledge and cultural continuity. Young participants also learn the spiritual meanings of festivals, developing a sense of belonging and identity that strengthens community cohesion.

Kalash Cuisine, Special Dishes, Culinary Traditions, and Gastronomic Heritage