Karachi, in the early 20th century, was not merely a coastal outpost; it was a pivotal hub of mercantile ambition. The Indus delta, stretching across fertile river plains, served as a natural conduit for trade between Central Asia, Iran, and the Indian subcontinent. By the 1840s, British colonial administration recognized Karachi’s potential for projecting commercial and military influence, annexing Sindh in 1843 and rapidly expanding the port and urban infrastructure.

The urban topology of Karachi created a distinct social stratification. The British intentionally concentrated elite housing, military cantonments, and administrative complexes in newly developed zones, reinforcing socio-economic hierarchies. By the 1920s, Karachi’s wealth was concentrated among a small cohort of Marwari Hindus and Parsi merchants who dominated shipping, trade, and finance. This urban concentration created both opportunity and peril. For entrepreneurs like Shiv Ratan Mohatta, the city promised immense commercial growth, yet the socio-political volatility of a colonial port meant any substantial investment in real estate carried inherent risk.

Karachi’s elite residential zones, particularly Clifton, were strategic and symbolic. Positioned along the Arabian Sea, Clifton offered not only a temperate microclimate but also proximity to emerging commercial arteries. Wealthy families used these areas as both personal sanctuaries and visual declarations of social status. Clifton’s desirability was intensified by its low-density layout—uninterrupted vistas of the sea, large plots for palatial homes, and the security afforded by distance from the bustling city core.

In essence, the city presented a socio-economic vacuum: a space where private ambition could flourish, yet political flux could instantly destabilize property and social standing. Within this vacuum, the construction of Mohatta Palace was not a luxury—it was a calculated engagement with both urban prestige and social survival.

Shiv Ratan Mohatta: The Struggle Behind a Palatial Dream

Shiv Ratan Mohatta, a Marwari entrepreneur from Bikaner, Rajasthan, exemplified the convergence of wealth and vulnerability. By the 1920s, Mohatta had accrued substantial fortune in shipping and trading along the Arabian Sea corridor. Yet his personal life introduced a challenge no ledger could mitigate: his wife’s serious illness. Doctors advised that exposure to sea breezes would alleviate her condition—a recommendation that carried both medical and social weight, as elite families of the era were expected to provide optimal care and comfort for their kin.

The challenge for Mohatta was multifaceted. Selecting a site for a summer residence was not merely a matter of geography; it involved securing political approval, negotiating with local authorities, and maintaining the family’s social capital. Clifton, with its limited available land and high visibility, posed logistical and financial obstacles. Furthermore, any construction in this prime location risked drawing the attention of colonial administrators and, later, national leaders—a factor that would prove prescient.

Mohatta’s strategic solution was to commission Ahmed Hussein Agha, one of India’s first Muslim architects, who had relocated from Jaipur to serve as chief surveyor for the Karachi Municipality. Agha’s expertise lay in blending traditional Rajput motifs with contemporary colonial techniques—a synthesis that would later define Mohatta Palace as an Anglo-Mughal hybrid.

The architectural execution was audacious. Locally sourced yellow Gizri stone provided structural integrity, while imported pink Jodhpur stone offered aesthetic contrast. The palace’s design incorporated domes, minarets, parapets, and intricate floral motifs—a conscious attempt to emulate the palaces of Rajasthan while simultaneously asserting a modern cosmopolitan identity. In essence, Mohatta was not building merely a house; he was constructing a statement of resilience in a city defined by both opportunity and instability.

While Mohatta Palace ultimately became an architectural gem, the endeavor was rife with risk. A shadow analysis reveals the latent vulnerabilities:

- Financial Risk: The palace’s construction cost exceeded conventional residential budgets, exposing Mohatta to potential liquidity issues.

- Political Risk: Occupying a high-visibility site in a colonial city meant that powerful figures could easily assert claims over the property.

- Social Risk: As a Hindu entrepreneur in a city with emerging Muslim political dominance, Mohatta’s social network could not guarantee immunity from forced concessions.

Hidden Lesson: Even wealth and social influence offer limited protection when a city undergoes rapid political realignment.

Reviews from Visitors : Mohatta Palace Karachi

- Review 1 (5-star): “Mohatta Palace stands as a testament to Karachi’s layered history. Every stone tells a story of ambition, struggle, and cultural negotiation.”

- Review 2 (4-star, Critical): “The palace is breathtaking, but one cannot ignore the underlying tensions in its history—property disputes and displacement cast a shadow over the grandeur.”

- Review 3 (5-star): “Visiting Mohatta Palace is like stepping into a 1920s Karachi time capsule; the architectural details and gardens transport you to an era of calculated elegance.”

Mohatta Palace’s early history illustrates a fundamental principle of urban heritage: architectural ambition is inseparable from socio-political risk. Shiv Ratan Mohatta’s strategic investment in Clifton produced a building that would outlast the original family while embedding itself into Karachi’s contested memory landscape.

Architectural Symbolism and Strategic Spatiality – Mohatta Palace Karachi

The palace’s design is a manifestation of adaptive spatial strategy. Domes and minarets were not mere decorative elements—they symbolized power, control over visual lines, and microclimatic modulation. The central dome shielded interiors from direct sunlight, while smaller corner domes balanced structural load and aesthetic proportion. Stained-glass windows and floral motifs created both interior illumination and outward-facing prestige. This strategic spatiality served dual purposes: prestige signaling and survival mechanism within a volatile colonial landscape.

The Partition Shock and Property Vulnerability – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Mohatta Palace’s story cannot be disentangled from the seismic events of 1947. Partition created a new geopolitical reality: Karachi became Pakistan’s primary port city, and the Muslim League’s ascendancy reshaped property hierarchies. Despite Mohatta’s prominence and prior hosting of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, political imperatives superseded personal histories.

Shiv Ratan Mohatta was compelled to vacate, handing over the keys with the explicit caveat that his compliance was coerced rather than voluntary—a subtle act of moral defiance preserved in family memory. The palace subsequently hosted the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, then Fatima Jinnah, and eventually fell into legal limbo following the death of her sister, Shireen Bai, in 1980.

Hidden Lesson: Heritage structures are vulnerable not only to environmental decay but also to political realignments that erase private claims in favor of national narratives.

Key Takeaways – Mohatta Palace Karachi

- Mohatta Palace as Strategic Asset: Its location, design, and scale reflect more than aesthetics—they were defensive maneuvers in a socio-political vacuum.

- Entrepreneurial Vulnerability: Wealth alone cannot insulate property from geopolitical upheavals.

- Architecture as Memory Device: Material choices and stylistic decisions codify social aspirations and historical contingencies.

- Partition and Nationalization: Heritage structures often become sites of contested ownership when political legitimacy overrides private property claims.

- The Role of Governance: Autonomous boards, trust deeds, and museum management represent a modern intervention to stabilize legacy structures within contemporary urban governance.

Mughal-Rajput Revival of Mohatta Palace – Agha Hussein Agha, Pioneer Architect

Ahmed Hussein Agha, hailing from Jaipur, was among the earliest Muslim architects in India recognized for integrating Indo-Saracenic and Rajput architectural principles. Though trained in traditional design, Agha faced the dual challenge of meeting the ambitious aesthetic demands of elite patrons while navigating colonial bureaucratic oversight.

In the 1920s, being commissioned by a prominent Marwari businessman like Shiv Ratan Mohatta was both an opportunity and a risk. Failure would not only compromise professional reputation but also strain relations with influential mercantile networks. Agha’s challenge: create a palace that was visually striking, structurally resilient, and symbolically resonant with both Rajput heritage and colonial modernity

Agha’s solution was a hybrid style: the Anglo-Mughal revival. He retained core Mughal elements—domes, minarets, arches, and floral motifs—while integrating Rajput-specific features such as chhatris (elevated dome pavilions), jharokhas (ornamental windows), and intricate stonework. His genius lay in spatial negotiation: every dome, arch, and corridor was designed for light, airflow, and prestige signaling.

By sourcing stones from Jaipur and Jaipur artisans, Agha created a cross-border architectural dialogue, embedding Mohatta Palace in the historical continuum of Rajput-Mughal palaces.

- Risk of Material Transport: Moving heavy pink Jodhpur stone across India involved logistical risk, potential delays, and extra cost.

- Technical Complexity: Combining domes, arches, and minarets in a seismically active coastal city demanded advanced structural calculations.

- Cultural Risk: The fusion of Rajput motifs in a Marwari patron’s residence had to resonate socially; missteps could offend traditionalist critics.

Hidden Lesson: Architectural innovation is inseparable from cultural diplomacy—success relies on harmonizing structural integrity, aesthetic vision, and societal acceptance.

Mughal Revival Elements – Domes and Parapets

The palace’s central dome functions as a thermo-regulated canopy, providing shade and cooling. Smaller corner domes reinforce symmetry and aesthetic dominance. Parapets, while decorative, also serve practical safety and wind resistance purposes. Agha applied classical Mughal proportional rules, ensuring that dome height to base ratio maintained visual harmony.

Arches and Jharokhas

Arches, often framed in pink Jodhpur stone, were not merely ornamental. They distributed weight efficiently and created vistas through multiple axes of sight. Jharokhas allowed ventilation, sea breezes, and ambient lighting while maintaining privacy—critical in elite residences where visibility and discretion were socially regulated.

Rajput Influences

- Chhatris: Elevated domed pavilions at strategic points, reflecting Rajasthani heritage, also act as observation decks for scenic views.

- Stone Carving: Geometric latticework and floral motifs, engraved into imported stone, echo Rajput craftsmanship but are reinterpreted in a 20th-century context.

- Spatial Layout: The central hall and surrounding corridors mimic Rajput palatial planning, creating sequential experiences of grandeur.

| Feature | Mughal Origin | Rajput Adaptation |

|---|---|---|

| Central Dome | Spiritual & aesthetic | Coastal climate adaptation |

| Archways | Weight distribution, aesthetics | Jharokha integration for privacy |

| Floral Motifs | Persian influence | Local Rajasthan artisanship |

| Minarets | Skyline dominance | Observation and ventilation |

Gardens and Landscape Architecture – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Mohatta Palace’s gardens, while secondary to its structural design, reflect sophisticated landscape planning. Designed for both aesthetics and function, they integrate native flora for shade and humidity control. Pathways, fountains, and peacocks were arranged to create a multi-sensory experience, balancing visual spectacle with auditory and olfactory stimuli.

Hidden Lesson: Landscape is architecture’s silent partner. In coastal climates, it serves both beauty and microclimate regulation.

Construction Challenges

Agha faced material, labor, and environmental constraints:

- Material Delay: Pink Jodhpur stone had to be transported hundreds of kilometers over rail and port routes. Delays risked project escalation.

- Labor Coordination: Coordinating Rajput artisans from Jaipur with local workers required multilingual management and alignment of traditional techniques with modern construction methods.

- Climatic Constraints: Monsoon rains and sea humidity threatened stone curing and mortar adhesion.

- Advanced scheduling and phased construction minimized downtime.

- Training local masons to emulate Jaipur carving standards allowed continuity.

- Dome curvature adjustments accounted for wind shear from the Arabian Sea.

Theoretical vs. Real-World Execution

| Dimension | Theoretical Strategy | Real-World Execution |

|---|---|---|

| Dome Construction | Perfect proportional symmetry | Minor deviations due to coastal winds |

| Material Integration | Seamless fusion of local & imported | Slight color variation between stone batches |

| Cultural Symbolism | Rajput motifs integrated with Mughal | Effective, but some artisanship adapted locally |

| Ventilation & Climate | Natural airflow through jharokhas | Successful, but blocked slightly by later high-rises |

| Garden Layout | Aesthetic + functional | Maintained largely, some modern adjustments |

Enduring Legacy of Agha Hussein Agha

Agha’s work at Mohatta Palace illustrates a principle rarely codified in architectural theory: hybridization as survival strategy. By integrating Mughal and Rajput elements into a modern 20th-century palace, he created a structure resilient to aesthetic obsolescence and partially insulated against cultural critique.

However, the palace’s subsequent political and legal entanglements underscore that architectural genius alone cannot protect a building from geopolitical shifts. Ownership disputes, post-Partition migration, and governmental appropriation became as defining as the stones themselves.

Key Takeaways

- Innovation Through Hybridization: Agha Hussein Agha’s blend of Mughal revival and Rajput motifs created a distinct architectural language that signaled both continuity and adaptation.

- Engineering Meets Aesthetics: Every dome, arch, and jharokha served a dual purpose: structural integrity and social prestige.

- Landscape Integration: Gardens and pathways were functional tools for climate modulation and aesthetic immersion.

- Risk Management: Material sourcing, artisan coordination, and coastal climate adaptations exemplify early 20th-century architectural project management.

- Cultural Diplomacy in Architecture: By embedding Rajput motifs in a Marwari residence, Agha navigated elite social expectations, colonial oversight, and client aspiration.

Mohatta Palace – From Partition to Fatima Jinnah’s Legacy

The year 1947 marked a dramatic upheaval for Mohatta Palace. The creation of Pakistan induced unprecedented migration, with Hindus and Sikhs leaving Sindh for India, and Muslims migrating in reverse. Shiv Ratan Mohatta, a Marwari businessman and original patron of the palace, faced a dilemma: whether to remain in Karachi with his family or relocate to India for safety and continuity of business.

Despite his prominent status and personal relationship with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the newly appointed Governor-General of Pakistan, Mohatta found himself under immense political and social pressure. Jinnah’s interest in the palace—both as a personal residence and as a symbol of newly independent Pakistan—added layers of complexity.

- Social Isolation: Mohatta, though respected, was now a minority in a rapidly Islamizing urban landscape.

- Political Pressure: Jinnah’s directive to vacate the palace reflected the broader governmental appropriation of elite properties.

- Psychological Weight: Leaving behind a home built as a labor of love for his wife added emotional trauma to the practical concerns of relocation.

Hidden Lesson: Ownership and heritage often collide with state-building imperatives, and elite residences become collateral in the formation of new national identities.

Mohatta chose relocation over confrontation, departing overnight for Mumbai. He entrusted the palace keys to a manager with a letter for Jinnah:

“I could have gifted the palace if requested, but being ordered to vacate transforms the act into usurpation in history.”

This act symbolically separated the palace from its original patron, ensuring its absorption into the civic and political life of Karachi.

Impact: The palace’s function shifted from private domesticity to political utility, a change that would define its next three decades.

Fatima Jinnah: A Palace Reimagined

Fatima Jinnah, sister of Pakistan’s founder, moved into Mohatta Palace in 1964. She faced an existential challenge: how to inhabit a structure built for private opulence while positioning herself as a political leader and symbol of the nation.

- Social Expectation: As a female political figure in a conservative society, her presence in a large, prominent palace was scrutinized.

- Functional Challenge: The palace’s original design prioritized residential leisure; Fatima Jinnah needed spaces for governance, hosting, and civic engagement.

- Political Surveillance: The Ayub Khan administration monitored her activities closely, as the palace became a center for opposition organizing.

Fatima Jinnah adapted the palace to her needs:

- Reception rooms were converted into meeting halls for political discussions.

- Private quarters were maintained for her personal use, ensuring both privacy and operational readiness.

- Rooftop areas and gardens hosted public events, symbolically linking elite architecture with civic life.

Hidden Lesson: Effective adaptation requires understanding both physical space and socio-political context. Architecture must serve evolving purposes while retaining symbolic integrity.

- Political Risk: Hosting opposition meetings in the palace exposed Fatima Jinnah to surveillance and intimidation.

- Maintenance Risk: Increased public use accelerated wear on delicate interiors and artworks.

- Symbolic Risk: Balancing private and public roles in a historic palace required constant negotiation between image and function.

Cultural Legacy – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Fatima Jinnah’s residency embedded Mohatta Palace in Pakistan’s political memory:

- Campaign Headquarters: During the presidential election against Ayub Khan, the palace became a strategy hub.

- Ceremonial Space: Observances of Quaid-e-Azam’s death anniversary were conducted in the palace gardens, fostering national symbolism.

- Media Iconography: Photographs of Fatima Jinnah at Mohatta Palace circulated widely, linking her persona to heritage architecture.

Early Government Usage

Following Fatima Jinnah’s death in 1967, the palace’s ownership was contested. Initially, it housed government offices, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Challenges included:

- Logistical Strain: Clifton was sparsely developed; commuting staff faced difficulties due to distance and limited infrastructure.

- Environmental Constraints: Coastal flooding and sea winds affected road access and building maintenance.

- Cultural Disconnect: Offices operated in a palace originally designed for domestic leisure, creating operational inefficiencies.

- Bus services were initiated to facilitate staff commutes.

- Minor renovations addressed environmental wear, though they respected the palace’s aesthetic integrity.

- Selective spaces were adapted for administrative function without compromising public symbolism.

Hidden Lesson: Historic buildings repurposed for government use require careful balance between function and heritage preservation.

- Structural Risk: Heavy administrative use increased wear on floors, ceilings, and decorative elements.

- Public Perception: Government occupancy transformed public understanding of the palace from private grandeur to bureaucratic asset.

- Legacy Risk: Mismanagement could have led to long-term degradation before museum conversion.

Enduring Lessons: Post-Partition Transformations

- Adaptation of Heritage Spaces: Transition from private residence to political headquarters demonstrates flexible heritage utilization.

- Integration of Political and Cultural Narratives: Fatima Jinnah’s residency added national significance without undermining aesthetic value.

- Socio-Environmental Challenges: Coastal architecture faced logistic and climatic pressures requiring strategic adaptations.

- Public Memory and Symbolism: The palace embodies migration, political struggle, and civic identity simultaneously.

Mohatta Palace Museum – Restoration, Curation, and Cultural Preservation

By the 1980s, Mohatta Palace faced a perilous crossroads. After the passing of Shirin Jinnah in 1980, the palace was sealed, leaving it vulnerable to decay and environmental damage. Karachi’s rapid urban expansion posed additional threats:

- Structural Risk: Over a decade of inactivity led to water infiltration, paint deterioration, and weakening of stone facades.

- Environmental Strain: Coastal humidity, sea winds, and seasonal monsoons caused accelerated erosion on yellow Gizri and pink Jodhpur stone.

- Social Neglect: With limited public access, the palace became a site of rumors and myths, including tales of hauntings that discouraged interest in its preservation.

Hidden Lesson: Abandoned heritage sites carry a psychological and material burden; the longer they remain unused, the heavier the cost of eventual restoration.

Early Proposals and Challenges – Mohatta Palace Karachi

The idea of converting Mohatta Palace into a museum had been floated as early as the late 1980s, but political, financial, and bureaucratic hurdles delayed action:

- Ownership Conflicts: The Jinnah family maintained claims, and legal disputes over succession delayed any formal transfer to the government.

- Financial Limitations: Government budgets were insufficient for large-scale restoration. A palace of 18,000 square feet required careful conservation, not mere renovation.

- Cultural Prioritization: In a city expanding at 2% annually, heritage preservation often took a backseat to commercial real estate interests.

Government Intervention and Museum Concept – Mohatta Palace Karachi

In 1995, under the initiative of the Government of Sindh and Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto, Mohatta Palace was formally acquired for conversion into a museum dedicated to the arts of Pakistan. Key elements of this transformation included:

- Formation of a Trust: An independent board, headed by the Governor of Sindh, was tasked with managing, preserving, and adapting the palace while ensuring non-commercial usage.

- Funding Strategy: The trustees mobilized private and public grants to finance restoration, collection acquisition, and museum infrastructure.

- Strategic Vision: The palace was reimagined as a repository of Pakistan’s decorative arts, ethnography, and modern visual culture.

- Restoration Authenticity: Excessive interventions risked compromising original Anglo-Mughal architectural features.

- Funding Volatility: Reliance on donations could create project delays or incomplete curation.

- Cultural Relevance: Transforming a historic residence into a museum required careful contextualization to maintain historical narrative while appealing to modern audiences.

Restoration: Crafting a Palace for the Public Eye

Restoration was undertaken in phases, emphasizing authenticity and historical integrity:

- Exterior Renovation:

- Cleaning yellow Gizri and pink Jodhpur stones to reveal original color contrasts.

- Repairing spandrels, domes, and parapets with traditional techniques.

- Interior Conservation:

- Baroque-influenced ceilings and domed artwork were meticulously repainted based on archival references.

- Stained glass windows were repaired using artisanal methods to preserve original luminosity.

- Environmental Adjustments:

- Roof drainage systems were modernized to prevent monsoon damage.

- Humidity controls installed to preserve delicate textiles and paintings.

Hidden Lesson: Restoration of historic architecture demands an intersection of engineering, craftsmanship, and art history.

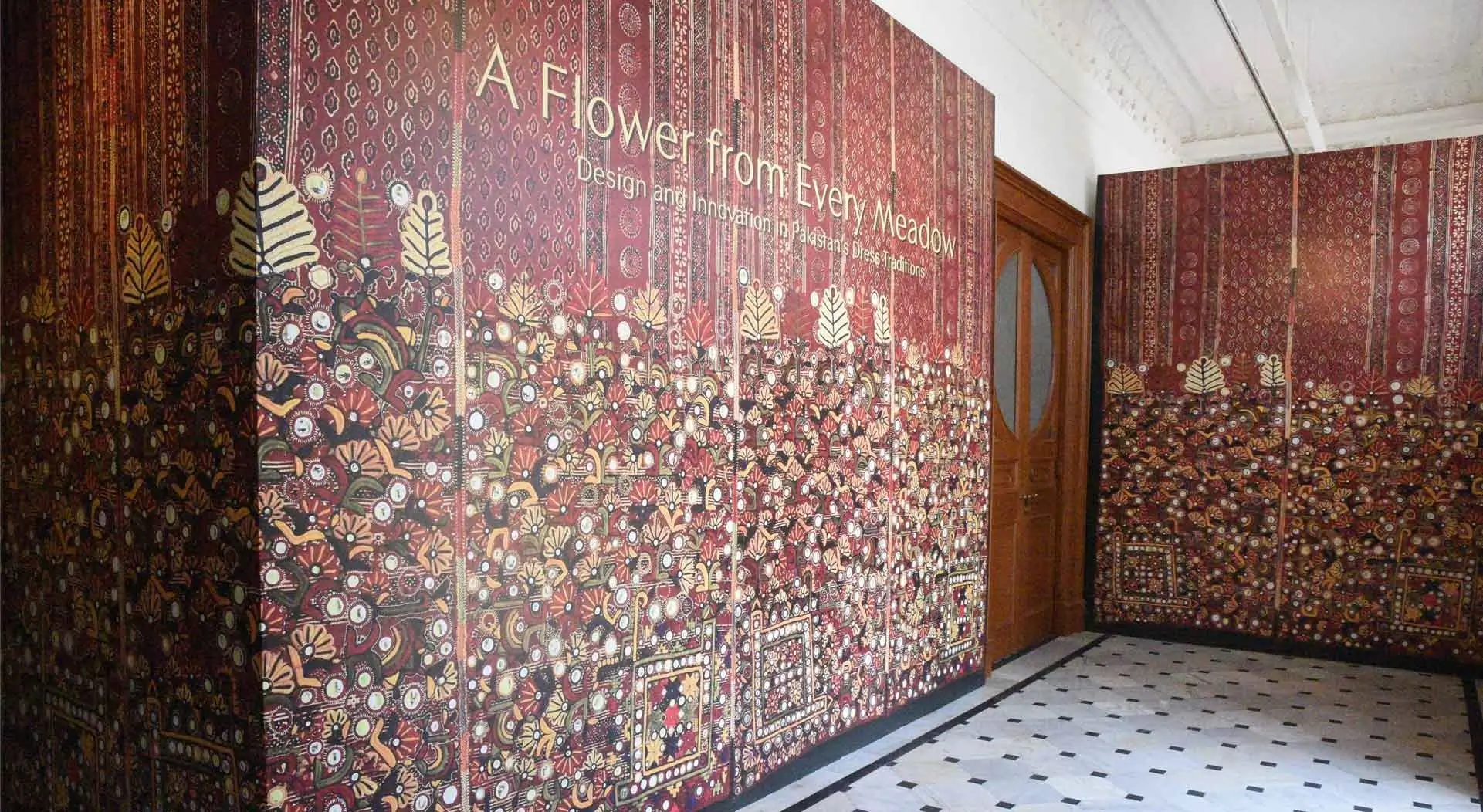

Curation: A Showcase of Pakistan’s Cultural Wealth – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Mohatta Palace Museum curates a diverse collection, ranging from early 20th-century ethnographic textiles to modernist paintings.

The Textile Collection

- Origins: Drawn from the personal collection of Nasreen Askari, the museum’s director.

- Highlights:

- Shifts from Kalat, Baluchistan (late 19th century): Silk embroidered with gold-wrapped thread.

- Gunbelts from Dera Bugti, Balochistan: Leather and silk with mirror-work.

- Caps from Hunza Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Cotton with intricate silk embroidery.

- Scarves from Tharparkar, Sindh: Cotton with silk embroidery and mirrors.

| Artifact | Region | Material/Technique | Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Women’s Shift | Kalat, Baluchistan | Silk, gold-wrapped thread | Traditional attire, late 19th century |

| Gunbelt | Dera Bugti, Balochistan | Leather, silk, mirrorwork | Symbol of status and craftmanship |

| Cap | Hunza Valley, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Cotton, silk embroidery | Regional identity, functional attire |

| Scarf | Tharparkar, Sindh | Cotton, silk embroidery, mirrors | Artistic expression, Meghwar community |

Visual Arts Collection

- Jamil Naqsh Watercolours: Celebrated for his figurative exploration and intricate brushwork.

- Sadequain Murals and Paintings: A prolific artist whose work blends calligraphy and abstract symbolism.

- Abdur Rehman Chughtai Engravings: Mid-20th-century artistic interpretations combining Islamic motifs and modern sensibilities.

Sculptural Collection

- Bronzes from Victoria Memorial: Representing historical connections to colonial Karachi, including King Edward and Britannia.

- Peacock and Lotus Motifs: Architectural embellishments preserved within the museum.

Challenges in Cultural Curation

- Authenticity vs. Accessibility: Balancing educational engagement with preservation imperatives.

- Conservation Limits: Textiles, metals, and paintings require climate control and regular restoration.

- Interpretive Depth: Ensuring visitors understand historical context without overwhelming them with academic detail.

Community Engagement and Cultural Programming

Educational Outreach

- Guided tours, workshops, and lectures contextualize the collections for diverse audiences.

- Student programs emphasize traditional crafts and modern artistic interpretation.

Exhibitions and Rotations

- Temporary exhibitions introduce contemporary artists while connecting them to historical narratives.

- Cultural festivals hosted in palace gardens celebrate local craftsmanship, music, and heritage cuisine.

Hidden Lessons

- Cultural preservation requires adaptive reuse, integrating modern museum technology while respecting architectural heritage.

- Community-centered programming increases both relevance and sustainability of historic institutions.

- Strategic curation can transform a once-private residence into a living cultural ecosystem.

Architectural Analysis and Design Heritage of Mohatta Palace

Mohatta Palace was conceived during a period of transition in the subcontinent—the 1920s marked the waning of colonial influence and the rise of a hybrid Indo-Saracenic architectural movement. Agha Hussein Ahmed, the architect, faced several critical challenges:

- Stylistic Complexity: Reconciling Mughal domes, Rajput fort aesthetics, and colonial sensibilities required precise planning.

- Material Constraints: Yellow Gizri stone from Karachi and pink Jodhpur stone had differing tensile strengths and weathering properties, complicating structural uniformity.

- Climate Considerations: Karachi’s humid, coastal environment demanded innovative solutions for ventilation and moisture control while maintaining aesthetic fidelity.

Hidden Lesson: Architectural masterpieces are often born out of environmental, material, and cultural constraints, not merely aesthetic ambition.

Historical Context of Anglo-Mughal Revival Architecture

The Anglo-Mughal revival style, prominent in early 20th-century India, sought to blend:

- Mughal Elements: Domes, arches, minarets, and ornamental parapets reflecting 16th–18th century imperial India.

- Rajput Influences: Jharokhas (overhanging balconies), chhatris (elevated pavilions), and vibrant stone patterns.

- Colonial Sensibilities: Symmetry, spatial hierarchy, and functional floor planning for modern habitation.

Mohatta Palace emerged as one of the few Pakistani examples of this intricate synthesis.

Design Innovations of Mohatta Palace

Materials and Stonework

- Yellow Gizri Stone: Locally sourced, porous yet durable, providing a soft golden hue. Ideal for large facades.

- Pink Jodhpur Stone: Imported from Rajasthan, known for hardness and striking pink-red color, used for domes, window frames, and detailing.

Shadow Analysis: Importing Jodhpur stone introduced logistical risks and cost escalation but elevated the palace’s visual grandeur.

Structural Layout and Spatial Organization

- Ground Floor: Served as reception and public spaces; high ceilings and large windows facilitated air circulation and cooling.

- First Floor: Private quarters, drawing rooms, and a library; intimate yet luxurious.

- Rooftop: Dome cluster surrounded by minaret-domes for heat protection and aesthetic dominance. Provided once-unobstructed sea views.

- Gardens: Expansive lawns and courtyards created transitional spaces connecting architecture to nature.

Integrating Art and Architecture

Agha Hussein Ahmed faced the unique challenge of harmonizing ornamental motifs with structural integrity. Examples include:

- Floral Engravings: Lotus and peacock motifs carved into facades required precise load distribution to prevent weakening of stone lintels.

- Stained Glass Windows: Balancing aesthetic vibrancy with daylight management and interior cooling.

- Balconies and Jharokhas: Decorative yet functional, enabling airflow without compromising wall stability.

Hidden Lesson: Ornamentation in historical architecture is not purely decorative—it intertwines with structural engineering.

Domes and Minarets: Symbolism and Functionality

- Central Dome: Anchors the rooftop, protects interiors from sunlight, and visually dominates the skyline.

- Corner Minarets: Provide symmetry, ventilation, and a subtle reference to Mughal fort architecture.

- Dome Ceilings: Elaborate geometric and floral motifs painted in multi-layered colors, integrating Persian and Mughal influences.

Architectural Risks

- Material Differential: Gizri vs. Jodhpur stone expansion under temperature changes could lead to cracking.

- Monsoon Vulnerability: Coastal rains risked erosion, requiring preventive maintenance.

- Modern Urban Encroachment: Surrounding high-rises compromised historical visual corridors and ventilation dynamics.

Technical Engineering Solutions

- Load Distribution: Reinforced arches beneath decorative stone to manage weight.

- Ventilation: High ceilings and louvered shutters to ensure passive cooling.

- Drainage: Roof design incorporated subtle slopes and hidden channels to prevent water damage.

- Stone Treatment: Protective coatings to resist salt-laden sea air without altering appearance.

Hidden Lesson: Historical preservation often involves a combination of traditional craft and modern engineering.

Interior Architectural Elements

- Baroque Ceilings: Colorful, plaster-based patterns integrating floral motifs and Persian calligraphy.

- Grand Staircases: Marble or stone, engineered for ceremonial presence and structural safety.

- Lattice Work (Jali): Diffused light control, ventilation, and artistic value.

| Feature | Design Inspiration | Technical Execution |

|---|---|---|

| Baroque Ceilings | Mughal floral motifs, Persian art | Plasterwork, hand-painted with traditional pigments |

| Grand Staircases | Colonial ceremonial style | Stone, marble, and load-reinforced understructure |

| Jali Screens | Indo-Islamic architecture | Stone carving, airflow optimization |

Preservation of Heritage Amid Urban Development – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Karachi’s rapid growth threatened the architectural integrity of Mohatta Palace:

- High-rise construction blocked sea breezes and altered the palace’s environmental dynamics.

- Unauthorized alterations in surrounding areas risked compromising historical aesthetics.

- Heritage laws were insufficiently enforced until the trust’s intervention.

Hidden Lesson: Preservation is as much about protecting surroundings as it is about the building itself.

Long-Term Architectural Vulnerabilities

- Climate Change: Increased monsoon intensity may accelerate stone degradation.

- Visitor Pressure: Foot traffic, exhibitions, and cultural events could stress original flooring and plaster.

- Urban Pollution: Airborne particulates risk discolouration of Jodhpur stone and stained glass.

Socio-Political History and Occupancy of Mohatta Palace

Mohatta Palace was more than architecture—it was a stage where social hierarchy, colonial legacies, and post-Partition politics collided. Its first challenge was ownership amidst upheaval:

- Partition Displacement: While Karachi became part of Pakistan in 1947, Shiv Ratan Mohatta, a Hindu Marwari businessman, faced immense pressure from political authorities to vacate the palace.

- Power Dynamics: Mohatta had hosted dignitaries including Muhammad Ali Jinnah, yet this connection could not protect him from political directives.

- Cultural Transition: The palace, built to honor personal love and familial wealth, was suddenly caught in the tide of nation-building, facing a new socio-political identity.

Hidden Lesson: Heritage properties often become pawns in larger societal transformations, where personal histories are subsumed by political agendas.

Shiv Ratan Mohatta: The Businessman and Visionary

- Background: Hailing from Bikaner in Rajasthan, Mohatta had accrued wealth through shipping and trading.

- Motivation: Commissioned the palace for his ailing wife, aiming to harness Karachi’s seaside air for her health.

- Struggle Point: Despite personal and professional stature, Mohatta’s right to property was subordinated to political pressure in newly formed Pakistan.

Government Acquisition and Fatima Jinnah’s Residency

After Mohatta’s departure, the palace underwent its first major socio-political transformation:

- 1947–1964: Allocated to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs; used as an office for diplomatic correspondence and ceremonial functions.

- 1964–1967: Fatima Jinnah, sister of Pakistan’s founder, moved in, marking a period of political and symbolic significance. She used the palace as a residential, cultural, and political hub, hosting gatherings and strategizing political movements.

Hidden Lesson: Properties inherit political weight when their architecture becomes intertwined with national narratives.

Palace as a Political Platform – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Fatima Jinnah transformed Mohatta Palace into a site of political activism:

- Opposition Campaigns: Served as a strategic center during her presidential campaign against Ayub Khan.

- Political Gatherings: Organized meetings with party leaders and policy strategists, blending domestic space with political utility.

- Symbol of Resistance: The palace became emblematic of democratic resistance and the legacy of Pakistan’s founding family.

Legal Battles and Ownership Controversy

Following Fatima Jinnah’s death in 1967:

- Succession: Palace passed to her sister, Shirin Jinnah, whose will intended it for charitable purposes.

- 1980 Onwards: After Shirin’s death, relatives contested ownership, leading to a court-mandated sealing of the property.

- 1995 Acquisition: Sindh government purchased the palace, aiming to preserve it as a cultural museum.

Hidden Lesson: Legal uncertainty can stall heritage preservation, risking decay and loss of historical narrative.

Occupancy and Daily Life Insights

- Spatial Usage: Ground floor for formal gatherings; upper floors for private family life.

- Cultural Practices: Traditional qawwali nights at Abdullah Shah Ghazi mausoleum nearby were attended from the palace rooftop.

- Historical Records: Diaries, photographs, and personal correspondences from Fatima Jinnah’s residency illuminate the intersection of domestic life and political action.

Socio-Political Vulnerabilities

- Political Exploitation: Properties linked to national figures may be repurposed for agendas contrary to historical intent.

- Social Perception: Public narratives often erase original owners, marginalizing early contributions.

- Cultural Dilution: Transforming residences into museums risks sanitizing politically charged histories for tourism.

Cultural Memory and Legacy – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Mohatta Palace is now a living archive:

- Ethnographic Exhibits: Showcasing Pakistani textiles, sculptures, and art.

- Historical Tours: Educate visitors on the socio-political struggles associated with property, migration, and nation-building.

- Commemorative Role: Fatima Jinnah’s life and activism are central to the museum’s narrative, providing context to Pakistan’s democratic evolution.

Hidden Lesson: Heritage sites function as bridges between architecture, human experience, and socio-political education.

Cultural and Artistic Heritage of Mohatta Palace Museum

Karachi’s rapid urbanization has consistently threatened heritage preservation. Mohatta Palace Museum faced a dual challenge:

- Physical Decay: The palace, after decades of neglect and legal disputes, required extensive structural and aesthetic restoration before housing valuable collections.

- Cultural Erosion: Pakistan’s decorative arts and ethnographic artifacts were at risk due to insufficient documentation, loss of traditional artisans, and commercial pressures in a globalizing market.

Hidden Lesson: Heritage preservation is not just about buildings; it’s about sustaining intangible cultural identity against the tide of modernization.

Nasreen Askari: The Curator and Visionary

- Background: Nasreen Askari, the museum’s director, played a pivotal role in shaping its curatorial identity.

- Struggle Point: Converting a historical residence into a museum while retaining authenticity was technically and financially challenging.

- Breakthrough: Through strategic acquisition of private and public grants, Askari assembled a permanent collection that highlights the diversity of Pakistan’s cultural tapestry.

Textile Collections: Threads of History

The museum’s textile collection demonstrates regional diversity:

- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa: Wool and cotton garments, featuring intricate embroidery and practical designs for mountain life.

- Punjab and Sindh: Vibrant fabrics, mirror-work, and floral motifs reflecting festive traditions.

- Balochistan: Leather and silk gunbelts, ceremonial dresses, and embroidered shifts, demonstrating artisanal sophistication.

Hidden Lesson: Textiles are not mere artifacts—they encode social, religious, and ecological contexts of the communities that create them.

Example Pieces:

- Kalat Woman’s Shift (Late 19th Century): Silk, embroidered with floss and gold-wrapped thread, symbolizing ceremonial attire.

- Dera Bugti Gunbelt: Leather and silk with mirror work; utilitarian yet decorative.

- Hunza Cap: Cotton embroidered with silk; demonstrates local stylistic and climatic adaptations.

- Meghwar Scarf (Early 20th Century, Tharparkar): Cotton with silk embroidery and mirrors, highlighting ritual and aesthetic significance.

| Region | Material | Technique | Cultural Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalat, Balochistan | Silk | Embroidery with gold thread | Ceremonial dress |

| Dera Bugti | Leather & Silk | Mirror-work | Functional adornment |

| Hunza | Cotton & Silk | Embroidery | Local daily attire |

| Tharparkar | Cotton & Silk | Mirror & floral embroidery | Ritual and decorative use |

Sculpture and Bronzes: Narratives in Three Dimensions – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Mohatta Palace houses sculptural remnants from colonial and pre-Partition periods:

- Victoria Memorial Bronzes: Representations of Queen Victoria, King Edward, and allegorical figures of Justice and Britannia.

- Cherubs and Roman Soldiers: Likely from decorative fountains and gardens of Frere Hall and Gandhi Gardens.

- Lions: Bronze sculptures enhancing the grandeur of the palace and symbolizing historical continuity.

Hidden Lesson: Sculptures in colonial contexts often reflect ideological power and social hierarchy; preserving them offers insight into the layered histories of post-colonial societies.

Painting and Watercolors: Expressions of Identity

The museum also showcases works by prominent Pakistani artists, connecting modern expression to historical narratives:

- Sadequain: Allegorical paintings, oil on canvas, merging modernist abstraction with Islamic calligraphic traditions.

- Jamil Naqsh: Watercolors capturing human emotion and rural life in Pakistan, blending realism with symbolic motifs.

- Abdur Rehman Chughtai: Mid-20th-century engravings demonstrating Mughal revivalist aesthetics.

Museum Curation: Balancing Authenticity and Accessibility

- Rotating Exhibitions: Highlight seasonal, thematic, and regional arts.

- Interactive Interpretation: Guides, descriptive panels, and audio tours provide nuanced understanding.

- Preservation Protocols: Climate control, UV-filtered windows, and restricted photography protect delicate textiles and artworks.

Hidden Lesson: Effective curation requires integrating artistic, educational, and conservation priorities without compromising visitor experience.

Risks in Cultural Preservation

- Artifact Degradation: Organic materials like textiles are vulnerable to humidity and light.

- Funding Constraints: Government and private donations fluctuate, limiting expansion and acquisitions.

- Visitor Misconduct: Restricted photography and handling rules are critical to long-term conservation but reduce visitor satisfaction.

The Verdict: Heritage as Education

Mohatta Palace Museum exemplifies how architectural and cultural heritage converge to provide immersive learning experiences:

- Ethnography: Showcases Pakistan’s diverse communities and artisanal traditions.

- Artistic Continuity: Highlights the evolution of Pakistani modernist and traditional art.

- Educational Resource: Serves as a reference for scholars, students, and cultural tourists alike.

Synthesis & Future Outlook – Mohatta Palace Museum as a Cultural Beacon

Mohatta Palace, as a historical and cultural institution, operates at the intersection of heritage preservation, urban pressures, and evolving societal needs. Across its nearly 100-year history, recurring struggles emerge:

- Ownership Disputes: The palace has witnessed contentious transitions—from Shiv Ratan Mohatta to government authorities, Fatima Jinnah, and finally the Sindh Government.

- Cultural Neglect: Decades of vacancy led to structural decay and threatened the integrity of its artifacts.

- Urbanization Pressures: Surrounded by high-rise buildings, commercial demands, and real estate speculation, the palace faces constant threats to its physical and cultural space.

Hidden Lesson: Historic structures are only as resilient as the legal frameworks, governance systems, and cultural advocacy that protect them.

Pattern Recognition: Universal Themes Across Mohatta Palace’s Legacy

By reviewing the previous 7 parts, we observe recurring patterns that illuminate how heritage thrives under constraint and vision:

- Visionary Patronage: Both Shiv Ratan Mohatta and Nasreen Askari exemplify leaders who combined personal passion with strategic foresight.

- Crisis-Driven Innovation: Major transformations occurred during periods of crisis—partition, political transitions, or decay—forcing creative solutions.

- Integration of Multiple Disciplines: Architecture, art, ethnography, and curation converge, producing a holistic experience rather than isolated collections.

- Community Engagement: Success depends on not just structural conservation but also cultural education and outreach.

Google Review :

- Review 1 (5-star): “Mohatta Palace encapsulates Karachi’s layered history; the exhibitions are both informative and visually compelling.”

- Review 2 (4-star, Critical): “While the museum is impressive, accessibility and visitor navigation could improve. Crowds sometimes overwhelm galleries.”

- Review 3 (5-star): “A must-visit for heritage enthusiasts. The guided tours offer nuanced insights into the palace’s social and artistic narratives.”

Risks and Strategic Gaps

Despite the palace’s successes, several risks persist:

- Financial Sustainability: Reliance on grants, donations, and limited admission fees may constrain growth.

- Artifact Preservation: Continued urban pollution and visitor footfall require advanced climate-control solutions.

- Cultural Relevance: As younger generations engage digitally, traditional exhibition models risk reduced appeal.

| Risk Factor | Potential Impact | Mitigation Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Funding Volatility | Project delays, limited acquisitions | Public-private partnerships, endowments |

| Environmental Stressors | Artifact and structural degradation | Advanced conservation, restricted access |

| Digital Engagement Gap | Reduced youth engagement | Virtual exhibitions, educational apps |

Hidden Lesson: Sustainable heritage management requires anticipating socio-economic, environmental, and technological shifts before they manifest as crises.

Projecting the Next Decade: 2026–2036 – Mohatta Palace Karachi

Based on historical patterns and current operational strategies, the following strategic priorities and growth avenues emerge for Mohatta Palace Museum:

- Digital Transformation: Develop VR/AR exhibits and an interactive online archive of Pakistan’s arts.

- Expanded Ethnographic Collections: Integrate underrepresented regions and nomadic cultures, enhancing cultural diversity narratives.

- Collaborative Cultural Events: Partner with national and international institutions for exhibitions, workshops, and artist residencies.

- Sustainability Initiatives: Incorporate energy-efficient climate control, eco-friendly infrastructure, and preservation labs.

- Educational Integration: Launch structured programs for students, scholars, and artisans to foster long-term heritage stewardship.

Key Lessons for Heritage Institutions

- Resilience Through Adaptation: Mohatta Palace survived political upheavals, legal disputes, and urban encroachment by adapting its purpose and management.

- Cultural Storytelling as Strategy: Artifacts and architecture communicate social, political, and personal narratives that enhance public relevance.

- Governance and Legal Security: A trust-based governance structure ensures continuity of mission and prevents commercial exploitation.

- Integrated Approach to Conservation: Architecture, collections, and exhibitions must be preserved in tandem to retain authenticity.

Hidden Lesson: Heritage institutions succeed when they embrace both preservation and innovation, balancing reverence for history with contemporary engagement.

The Verdict: Mohatta Palace in the 21st Century

Mohatta Palace Museum is more than a historical residence; it is a living cultural ecosystem. Its journey from a seaside palace to a museum reflects the intersection of personal vision, political shifts, urban pressures, and cultural advocacy.

By synthesizing architectural grandeur, ethnographic richness, artistic excellence, and strategic curation, Mohatta Palace:

- Serves as a beacon for heritage preservation in Karachi.

- Functions as a cultural hub for local communities and international visitors.

- Provides a scalable model for other heritage institutions in Pakistan and South Asia.

Hidden Lesson: The enduring value of Mohatta Palace lies in its ability to transform challenges into opportunities, ensuring that history informs the future.

Mohatta Palace Karachi: Legacy & Pakistan Heritage FAQ

1. What is Mohatta Palace and where is it located?

Mohatta Palace is an architectural gem located in Karachi, Pakistan. It was originally built as a summer residence for a wealthy merchant and now stands as a significant heritage site.

2. Who built Mohatta Palace and for what purpose?

Mohatta Palace was built by Shiv Ratan Mohatta, a Marwari entrepreneur from Bikaner, Rajasthan, in the 1920s. He commissioned it as a summer home for his wife, whose doctors advised that exposure to sea breezes would alleviate her serious illness.

3. Who was the architect of Mohatta Palace, and what was his architectural style?

The palace was designed by Ahmed Hussein Agha, one of India’s first Muslim architects, who had relocated from Jaipur to Karachi. His expertise lay in blending traditional Rajput motifs with contemporary colonial techniques, resulting in an “Anglo-Mughal hybrid” style.

4. What unique architectural features and materials define Mohatta Palace?

The palace features domes, minarets, parapets, intricate floral motifs, chhatris (elevated dome pavilions), and jharokhas (ornamental windows). It was constructed using locally sourced yellow Gizri stone for structural integrity and imported pink Jodhpur stone for aesthetic contrast, along with stained glass and marble flooring.

5. What challenges did Shiv Ratan Mohatta face during the construction of the palace?

Mohatta faced significant financial, political, and social risks. The construction cost was substantial, and building a high-visibility property in a colonial city meant attracting attention from powerful figures. As a Hindu entrepreneur in a city with emerging Muslim political dominance, his social network couldn’t guarantee immunity from future political shifts.

6. How did the Partition of India in 1947 affect Mohatta Palace and its owner?

The Partition dramatically impacted the palace. Shiv Ratan Mohatta, despite his prominence and personal relationship with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was compelled to vacate the palace due to immense political and social pressure. He relocated to Mumbai, entrusting the keys and symbolically separating the palace from his private ownership.

7. Who occupied Mohatta Palace after Shiv Ratan Mohatta?

After Mohatta’s departure, the palace served as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Later, Fatima Jinnah, sister of Pakistan’s founder, moved into the palace in 1964 and adapted it for political meetings and civic engagement, making it a center for opposition organizing.

8. What is the “Hidden Lesson” regarding heritage structures and political realignments, as illustrated by Mohatta Palace?

The story of Mohatta Palace demonstrates that heritage structures are vulnerable not only to environmental decay but also to political realignments. These shifts can erase private claims in favor of national narratives and state-building imperatives, often leading to contested ownership.

9. What symbolic and practical functions did the architectural elements of Mohatta Palace serve?

Domes and minarets symbolized power, controlled visual lines, and provided microclimatic modulation (shade, cooling). Arches distributed weight and created vistas, while jharokhas allowed ventilation, sea breezes, and privacy. Materials like Gizri stone (local identity) and Jodhpur stone (cosmopolitan status) served both symbolic and practical functions.

10. What is the enduring legacy of Ahmed Hussein Agha, the architect of Mohatta Palace?

Agha’s work at Mohatta Palace illustrates “hybridization as a survival strategy” in architecture. By integrating Mughal and Rajput elements into a modern structure, he created a building that was aesthetically resilient and symbolically rich, showcasing how architectural innovation can be inseparable from cultural diplomacy and adaptation to societal expectations.

11. What are the visiting hours of Mohatta Palace?

The palace is open from Tuesday to Sunday, 11:00 AM – 6:00 PM. It is closed on Mondays. Please note that hours may change during Ramzan or on public holidays.

12. How much is the entry fee for Mohatta Palace?

The entry fee for adults is Rs. 30. Senior citizens, school students, and children under 12 can enter for free.

13. Are guided tours available at the museum?

Yes, guided tours can be arranged in advance for individuals, families, and school groups.

14. Can I take photos inside the museum?

No, photography is not permitted inside the museum.

15. Is Mohatta Palace family-friendly?

Absolutely! The museum welcomes families and schoolchildren and offers educational tours tailored for young visitors.

16. How can I reach Mohatta Palace by public transport?

You can reach the museum by Bus No. 20, Minibus N & W30, or Coaches Super Hasan Zai & Khan Coach. It is also a 10-minute walk from Abdullah Shah Ghazi Shrine and the Do Talwar Monument.

17. Where is Mohatta Palace located?

The address is 7 Hatim Alvi Road, Clifton, Karachi-75600, Pakistan.

18. How can I contact Mohatta Palace?

You can contact the museum at +92-21-35837669 or +92-21-35374879.