Introduction — When Pakistani Feminist Restore What History Erased

Pakistan’s cultural memory resembles an archive full of torn pages, blank spaces, and deliberate silences. For decades, the artistic, intellectual, and political contributions of women were pushed to the margins—sometimes erased, sometimes distorted, sometimes deliberately forgotten. What survived were fragmented biographies, scattered newspaper mentions, a few interviews, and the personal memories of families who remembered their brilliance.

Yet even in absence, women have always been architects of Pakistan’s cultural identity: dancers, writers, poets, painters, educators, journalists, activists, intellectuals, and craftswomen. They shaped society from the edges because the center refused to acknowledge them.

This blog is a reclamation — a reconstruction of a narrative Pakistan should have inherited but never did.

It traces:

- the Pakistani feminist visual language of Shehzil Malik,

- the collective memory work of Herstories and Tehrik-i-Niswan,

- the global storytelling of Maliha Abidi,

- the conceptual sophistication of contemporary women artists of Pakistan like Adeela Suleman, Huma Mulji, Faiza Butt, and Ayessha Quraishi,

- and the historical women whose stories were either censored or erased.

It is not just a blog.

It is a counter-archive.

A space where lost voices are restored.

A conversation between past and present.

A reminder that Pakistani history is incomplete without women and women artists of Pakistan.

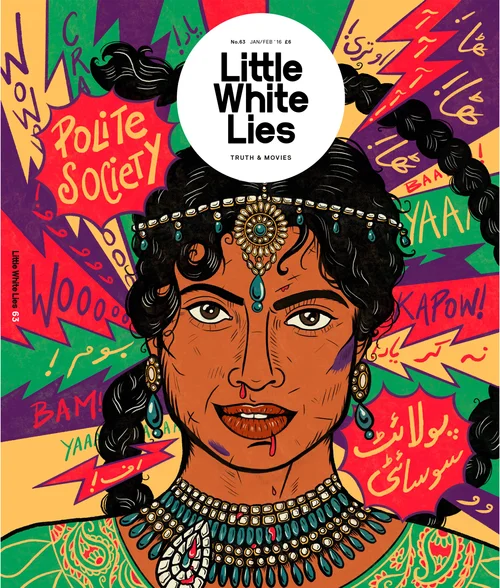

1. Shehzil Malik: Rewriting the Pakistani Imagination Through Feminist Art

Shehzil Malik does not draw women — she redraws the entire landscape in which women exist. Her bold lines, saturated palettes, and unapologetic subjects confront patriarchy not with aggression, but with storytelling. Her visual world insists on imagining what freedom could look like.

Her work has been celebrated globally — CNN, Forbes, BBC, DW — but its power lies in something deeper:

It asks Pakistan a question it avoids.

What would society look like if women felt safe, visible, and free?

1.1 A Lahore Childhood Inside a Gendered City

Growing up in Lahore, Shehzil observed what every girl in Pakistan intuitively learns:

- Take the longer route to avoid harassment.

- Keep your eyes down to avoid confrontation.

- Dress modestly to minimize attention.

- Don’t stay out too late.

- Don’t ride a bicycle.

- Don’t dream too loudly.

These are more than societal expectations. They are spatial restrictions. They map the city not as a shared environment but as a terrain full of invisible borders women must navigate.

Art became her rebellion.

Instead of accepting these constraints, she began illustrating worlds where these rules simply did not exist — where women took up space, claimed pleasure, expressed ambition, and occupied public streets without fear.

1.2 Narratives on Wheels, Space, and Sky

In Shehzil’s illustrated universe, women pedal bicycles with ease, roam through galaxies as astronauts, ride scooters with wind in their hair, look back at the viewer with boldness, not shame. Her characters are not idealized heroines; they are everyday women finally granted the freedom society denies them.

Shehzil’s artistic mission is not limited to representation.

It is psychological liberation.

She draws possibilities so women can recognize them.

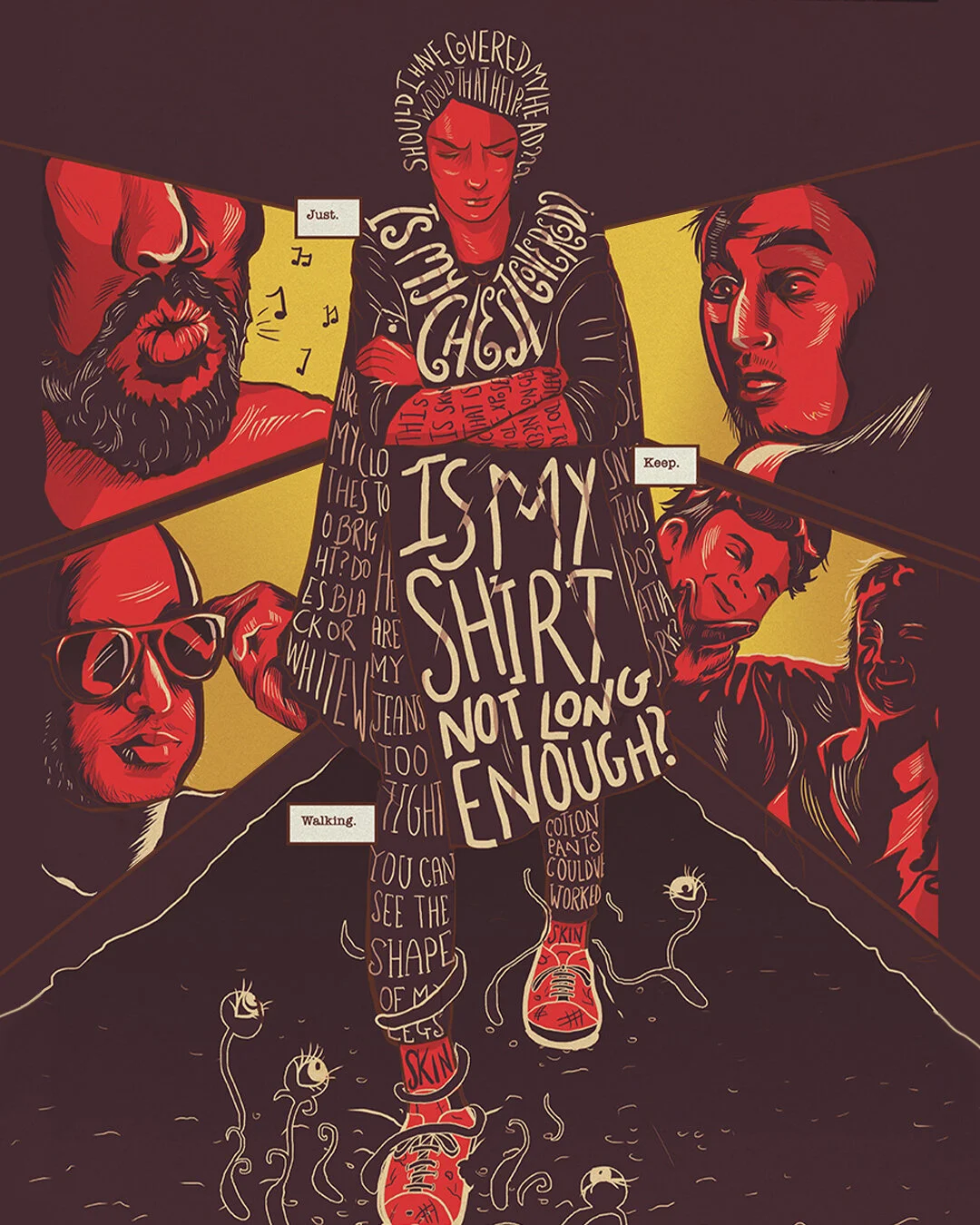

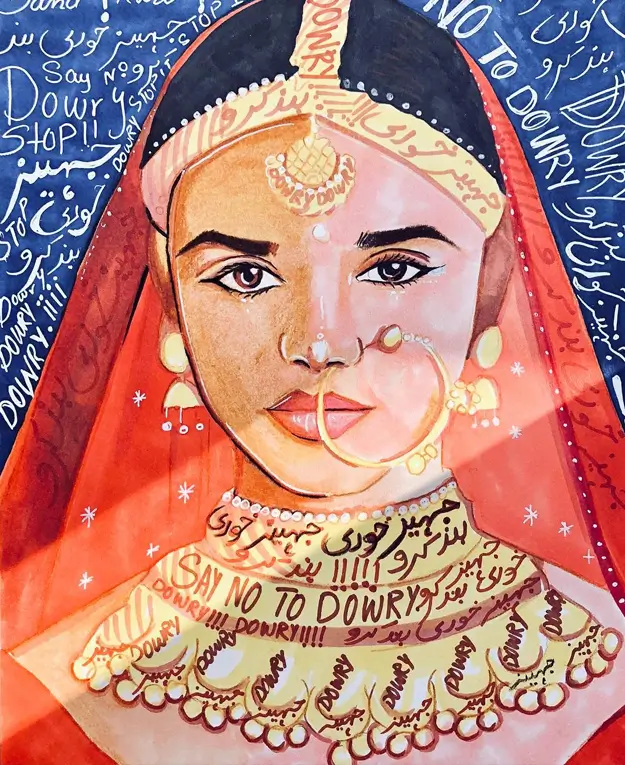

2. “IS MY SHIRT LONG ENOUGH?”: When Clothing Became Protest

In 2017, Shehzil launched her feminist fashion line: “Is My Shirt Long Enough?”

Its title alone is a provocation — a satirical jab at Pakistan’s obsession with women’s clothing lengths.

The line disrupted Pakistani fashion norms because it transformed clothing into political messaging:

- bold feminist slogans

- diverse female bodies

- illustrations celebrating women’s autonomy

- joyful aesthetics with radical undertones

Fashion, for Shehzil, was not a commercial venture. It was a mobile billboard of resistance. Every shirt worn in the public became a small-scale protest — a walking reminder that women deserve a life without policing, commentary, and restriction.

Her work sparked conversations in households, offices, universities, and online spaces.

Resistance became wearable.

Freedom became visible.

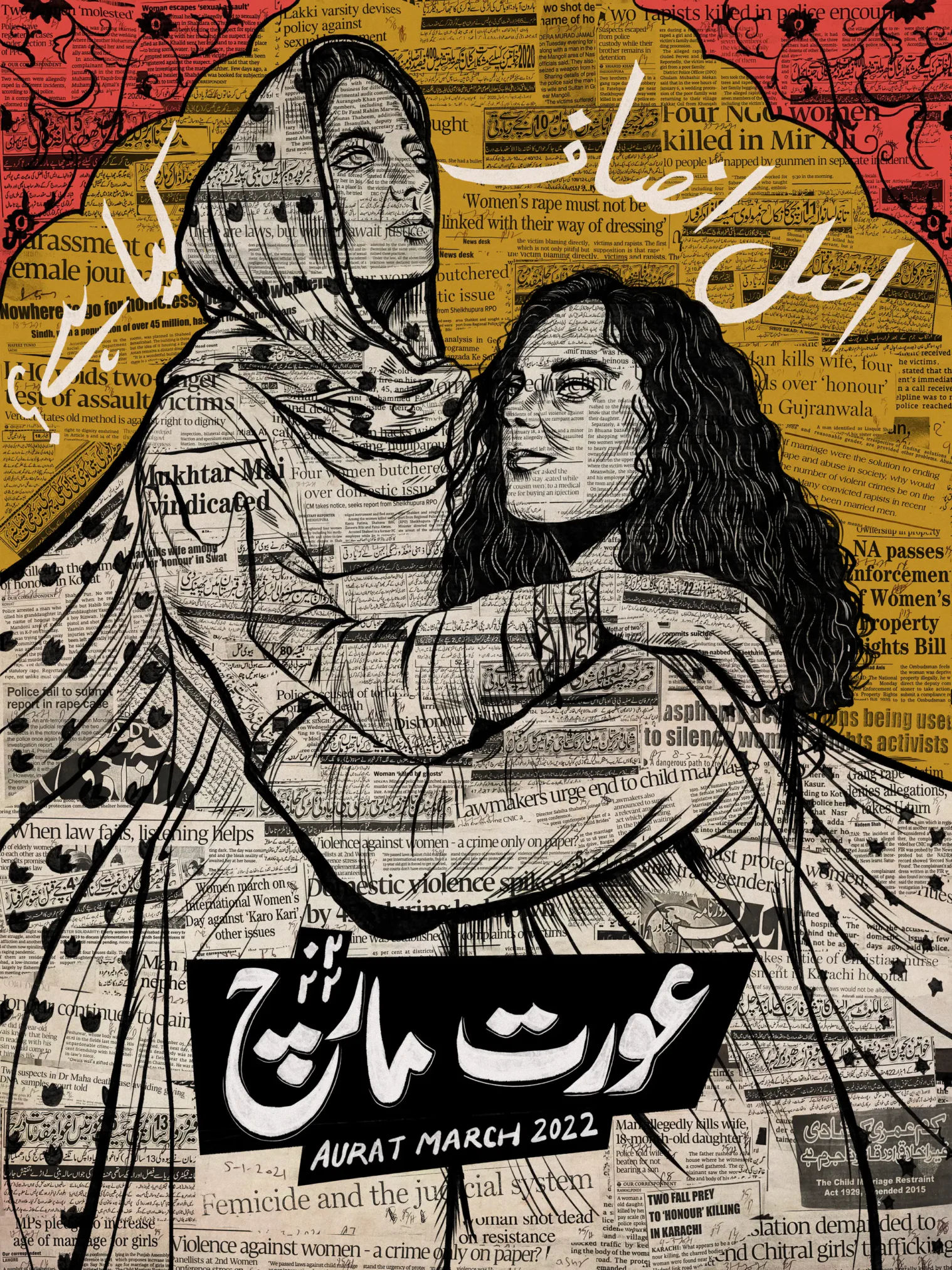

3. THE AURAT MARCH: Public Space as Feminist Battlefield

The Aurat March, which began in 2018, became a major cultural turning point in Pakistan. The movement united women from all walks of life to demand:

- bodily autonomy

- economic justice

- safety

- equal participation in public spaces

- an end to gender-based violence

Shehzil’s artwork became one of the March’s most recognizable visual identities. Her posters were seen everywhere — in the crowds, online, on news channels. She created imagery that was bold, hopeful, inclusive, and unafraid of confrontation.

Her statement about the Aurat March captures its essence:

“Aurat March unites women across Pakistan to demand their social and economic rights and demand an end to gender violence and discrimination. It’s about women taking charge of their own destiny and paving the way for their daughters.”

The Aurat March, much like Shehzil’s art, is not merely a protest. It is a monthly reminder that Pakistani history has been incomplete — and women are writing the missing chapters.

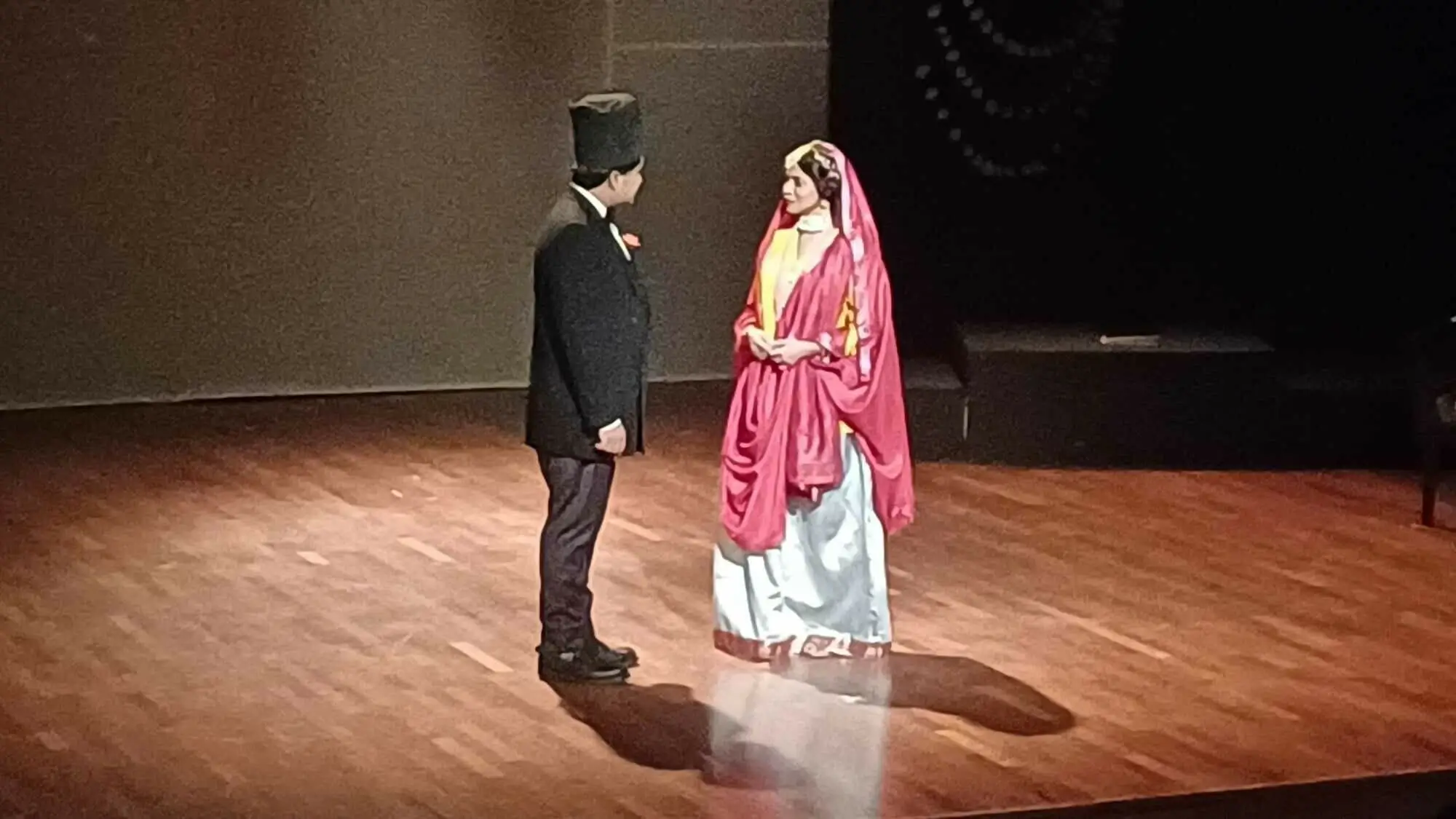

4. TEHRIK-I-NISWAN & “HERSTORIES”: Reclaiming Forgotten Women of Pakistan

Before hashtags, before digital activism, before contemporary Pakistani feminist art — there was Tehrik-i-Niswan, founded by the iconic Sheema Kermani. A dancer, activist, and cultural visionary, Sheema has spent decades reviving women’s erased histories through performance, theater, dialogue, and dance.

In their recent production, “Herstories,” the organization did something radical:

They placed forgotten women of Pakistan back into the spotlight.

These were not fictional characters.

They were real, brilliant, courageous women whose names never made it into textbooks.

4.1 Why Were These Women Forgotten?

Because they were:

- too bold

- too educated

- too loud

- too controversial

- too independent

- too “unfeminine” for patriarchy

History remembers those who fit the narrative. These women did not.

“Herstories” restores them — one performance at a time.

5. THE WOMEN “HERSTORIES” REVIVED

Here are the women resurrected from erasure:

5.1 Atiya Fyzee — The Intellectual Who Refused Silence

Atiya Fyzee belonged to an elite, educated family — but she was not content with privilege. She challenged expectations by speaking openly, writing boldly, and rejecting the veil at a time when such a choice was radical.

She was:

- a writer

- a traveler

- a feminist

- a cultural archivist

- a friend and intellectual companion of Allama Iqbal

Her letters with Iqbal reveal a relationship based on mutual admiration and respect — but patriarchy later tried to diminish or erase that intellectual bond.

After marriage, Atiya and her husband Samuel Fyzee became major patrons of art and culture. They envisioned an art institution in Pakistan — on land later occupied by the Arts Council of Pakistan.

But after Quaid-e-Azam’s death, the couple was driven out, their contributions dismissed, their archives neglected.

They died in poverty and obscurity.

“Herstories” brings them back.

5.2 Madam Azurie — The Ballet Star Turned Cultural Icon

Born to a German-Jewish father and Indian mother, Anna Marie Gueizelor reinvented herself as Madam Azurie, a dance pioneer who introduced classical arts to Pakistani cinema.

But General Zia’s regime (1977–1988) banned dance, destroyed livelihoods, and suffocated cultural expression. Madam Azurie’s career collapsed. She died with unfulfilled dreams — another casualty of state misogyny.

5.3 Parveen Qasim — The Kathak Dancer Silenced by Dictatorship

Trained in Kathak by her father, Parveen was a brilliant dancer whose art was cut short by state censorship.

Her story is one of tragedy:

A woman punished for cultural expression.

5.4 The Ghanshyams — Art Teachers Forced to Flee – the contemporary artists

Mr. and Mrs. Ghanshyam ran the Rhythmic Arts Centre in Karachi, where they taught music and dance. Under Zia’s dictatorship, they were forced to flee Pakistan to save their lives.

5.5 Sara Shagufta — The Poet Who Loved Too Fiercely for This World

Perhaps the most heartbreaking story in the series, Sara Shagufta lived a turbulent life marked by:

- poverty

- patriarchy

- institutional violence

- mental illness

Her poetry was raw, powerful, and prophetic.

Society punished her for being a woman who refused silence.

She ultimately took her own life at Drigh Road Station — a reminder that sometimes the world is simply too cruel to women who live honestly, another forgotten women of Pakistan.

6. HEROINES.PK: A Digital Archive Rebuilding National Memory and Pakistani Women in History

If “Herstories” uses theater to reclaim forgotten women of Pakistan, Heroines.pk uses digital architecture. It is one of the most extensive online archives dedicated to Pakistani women in:

- history

- sports

- medicine

- activism

- science

- literature

- public service

- education

- aviation

- law

- technology

Created by Pakistani researchers, designers, and activists, this project fills a vacuum in the national consciousness.

6.1 Why Heroines.pk Matters

Pakistan’s textbooks rarely feature women beyond a handful of superficial mentions. Students grow up learning about kings, generals, political leaders, male scientists, and male activists. The archive is a radical intervention because it:

- re-centers women as historical actors, not footnotes

- makes feminist historiography accessible

- provides representation for young girls

- documents women’s achievements that were previously unrecorded

Heroines.pk is not just a website — it’s a national corrective.

6.2 Restoring Role Models That The System Erased

Young readers discover women like:

- Asma Jahangir — lawyer, human rights defender, UN rapporteur

- Samina Baig — first Pakistani woman to summit Everest

- Arfa Karim — world’s youngest Microsoft Certified Professional

- Fatima Jinnah — political leader and pro-democracy icon

- Hina Rabbani Khar — Pakistan’s first woman Foreign Minister

- Ruth Pfau — the “Mother Teresa of Pakistan”

- Bilquis Edhi — humanitarian and nurse who saved thousands of infants

In a country where girls grow up hearing “you can’t,” Heroines.pk provides endless real examples of “you already did.”

7. MALIHA ABIDI: The Global Storyteller Who Paints Power– a contemporary artist

Where Shehzil Malik builds a Pakistani feminist world rooted in Pakistan, Maliha Abidi builds one that travels across continents.

A British-Pakistani visual contemporary artist, author, and activist, Maliha is known for her:

- neon-rich illustrations

- bold color palettes

- portraits of Brown women

- advocacy for women’s rights

- storytelling around identity, migration, and global inequality

Her work is political, celebratory, and deeply emotional.

7.1 Art as a Global Language

Maliha uses multiple mediums: acrylics, digital releases, ink drawings, graphic design, and mixed media. Her colors are not decorative — they are expressions of:

- defiance

- joy

- intersectionality

- cultural pride

- hope

Her signature style combines realism with bold hues, creating portraits that feel uplifting and powerful.

7.2 “Pakistan for Women”: A Landmark Publication

Maliha’s most influential project is her illustrated book “Pakistan for Women: Stories of Women Who Have Achieved Extraordinary Things.”

It is monumental for several reasons:

1 – It’s the first English-language illustrated book about Pakistani women heroes.

Before this book, no comprehensive visual guide existed.

2 – It features 50+ women in diverse fields.

From mountaineers to athletes, activists to poets.

3 – It introduces global audiences to Pakistani feminist narratives.

The book is sold worldwide and used in classrooms.

4 – It offers representation Brown and Muslim girls rarely receive.

Girls who never see themselves in cartoons or textbooks find themselves here.

Her portraits radiate gratitude, pride, and cultural beauty. Her work insists that Pakistani women are not defined by victimhood — they are leaders, creators, pioneers.

8. Contemporary Women Artists of Pakistan Reshaping Cultural Landscape

Now we enter the rich terrain of Pakistan’s fine art world — women artists of Pakistan creating bold, experimental, conceptual works exhibited globally in:

- Venice Biennale

- Art Dubai

- Lahore Biennale

- Fukuoka Asian Art Museum

- Tate Modern programs

- Museum of Modern Art programs

Each contemporary artist represents a different language of resistance.

8.1 ADEELA SULEMAN — Sculpting Violence, Memory, and Patriarchy

Adeela Suleman is one of Pakistan’s most important contemporary artists. Her practice explores:

- state violence

- gendered danger

- militarization

- martyrdom narratives

- fragility masked as strength

- social hypocrisy

8.1.1 The Language of Steel

She often uses:

- steel sheets

- metal filigree

- found objects

- domestic tools

- shields

- helmets

- armor forms

At first glance, her work looks ornamental — intricate, floral, delicate. But look closely, and you see:

- bullets

- weapons

- graves

- body silhouettes

- motifs referencing death

She contrasts beauty with brutality to reveal how violence becomes normalized in society.

8.1.2 Gender & the Domestic Battlefield

Her earlier works featured armor-like domestic objects — aprons shaped like bulletproof vests, corset forms made of metal. These sculptures reveal the invisible wars women fight inside their homes.

Her art says:

“A woman’s everyday life is a battlefield.”

8.1.3 The Amna Sharif Mughal Case

Her exhibition on extrajudicial killings sparked national debate when authorities attempted to censor her work. She resisted — and in doing so, became a symbol of artistic freedom in Pakistan.

8.2 HUMA MULJI — The Queen of Awkward Silences

Huma Mulji’s art is conceptual, humorous, surreal, and deeply political. She works with sculpture, installation, and photography. Her themes include:

- failure

- urban decay

- migration

- dislocation

- absurd bureaucracies

- infrastructure collapse

8.2.1 When the Absurd Becomes the Truth

Her most famous piece, “Arabian Delight,” featured a taxidermied camel stuffed into a suitcase — a commentary on:

- Gulf migration

- exploitation of labor

- dreams of prosperity

- the absurdity of modern survival

8.2.2 Humor as Resistance

Huma uses awkwardness and irony to expose the chaos of urban Pakistani life. Her work is less about beauty and more about truth — uncomfortable, messy, unresolved truth.

8.3 FAIZA BUTT — Ornamental Portraiture with a Political Edge

Faiza Butt merges miniature painting techniques with digital precision. Her art is visually stunning — floral, intricate, decorative — yet deeply political.

8.3.1 Challenging Western Orientalism

Her male portraits, inspired by media portrayals of Muslim men, beautify subjects who are otherwise vilified. She disrupts stereotypes by transforming these men into:

- sensitive

- complex

- emotionally vibrant

- fully human

8.3.2 Feminist Miniature Painting

Faiza uses:

- repetitive mark-making

- pastel hues

- delicate motifs

- hyper-detailed ink work

Her intention is clear:

To reclaim narratives and offer alternate beauty standards — especially in a world oversaturated with reductive depictions of South Asian masculinity.

8.4 AYESSHA QURAISHI — Meditation, Silence, and Inner Vision

Ayessha Quraishi stands apart. While others focus on sociopolitical issues, her work is internal — spiritual, contemplative, philosophical.

8.4.1 The Philosophy of “Open Presence”

Her abstract paintings explore:

- consciousness

- memory

- sensory experience

- inner landscapes

- meditative states

Her work invites viewers into a quiet space — a place where thought dissolves into sensation.

8.4.2 The Language of Layers

She works with:

- gestural strokes

- layered pigments

- textured surfaces

- minimal color palettes

Her paintings feel like breathing — inhalation and exhalation captured in pigment.

If Pakistani feminist art is a large ecosystem, Ayessha is its philosopher, asking:

“What remains when noise disappears?”

THE COMMON THREAD: RESISTANCE AS ART, ART AS RESISTANCE

Though their mediums differ, these contemporary artists share a mission:

To reclaim space — historical, social, emotional, political, archival, psychological.

Their art functions as:

- a form of protest

- a tool for memory

- a space for healing

- a challenge to patriarchy

- a rewriting of national history

Pakistani feminist art is not a movement — it is a continuum, stretching from early 20th-century women like Atiya Fyzee to modern digital activists like Maliha Abidi.

These women fill in the pages history left blank.

Conclusion — The Future Belongs to the Women Who Rewrite It

Pakistan’s cultural history has always been shaped by women — even when the world refused to acknowledge them. Their art, voices, archives, bodies, memories, and rebellions persisted through censorship, exile, silence, and erasure. What we see today is not a new awakening; it is a resurfacing. A return.

From Shehzil Malik’s boldly illustrated worlds to Maliha Abidi’s global visual storytelling, from the archival activism of Herstories and Heroines.pk to the conceptual brilliance of Adeela Suleman, Huma Mulji, Faiza Butt, and Ayessha Quraishi, Pakistani women are doing more than creating art — they are restoring what patriarchy tried to erase.

Their work is a bridge between the forgotten and the remembered.

Between the invisible and the undeniable.

Between the Pakistan that was recorded and the Pakistan that actually existed.

These women do not simply critique society — they redesign it, they are contemporary artists

They do not merely preserve history — they remake it, they are not forgotten women of Pakistan

They do not just occupy cultural spaces — they expand them, they will be part of Pakistani Women in the history of cultural space and art

And because of them, young girls growing up in Karachi, Lahore, Quetta, Gilgit, Hyderabad, D.I. Khan, or the diaspora no longer inherit an empty landscape. They inherit a rich, vivid archive of women who dared — women who imagined, created, resisted, and led.

Together, these creators and contemporary artists form the living heartbeat of Pakistani feminist art, transforming resistance into beauty and memory into a powerful force. As women artists of Pakistan continue to reclaim space, they ensure that the nation’s cultural future will be more truthful, more inclusive, and finally, more complete.

FAQs – Pakistani Feminist Art: Redefining Feminism, Culture, and Creative Resistance

- What is Pakistani feminist art and why does it matter?

Pakistani feminist art is a form of cultural expression where women artists use visual language to challenge social norms, patriarchy, and historical erasure, thereby expanding how feminism is understood and represented within Pakistan’s culture. - Who are some key artists featured in Pakistani feminist art?

Influential figures in this space include Shehzil Malik, Maliha Abidi, Adeela Suleman, Huma Mulji, Faiza Butt, and Ayessha Quraishi, all of whom use their work to explore identity, resistance, and cultural narratives. - How does Shehzil Malik contribute to feminist art in Pakistan?

Shehzil Malik reimagines societal narratives through bold, saturated visuals that confront patriarchal imagery and invite viewers to consider what female freedom and visibility could look like in Pakistani art. - What makes Maliha Abidi’s work significant in global feminist art?

As a British-Pakistani artist and author, Maliha Abidi creates visual narratives that highlight women’s achievements and stories across cultures, contributing to both local and international feminist discourse. - In what ways does feminist art act as resistance in Pakistan?

Feminist art in Pakistan functions as protest, memory work, healing, and a challenge to patriarchy, making art itself a form of creative resistance against cultural invisibility. - How does Pakistani feminist art help preserve women’s cultural history?

By restoring and amplifying stories often ignored or erased from mainstream historical narratives, feminist artists create counter-archives that reconnect Pakistan’s cultural identity with women’s experiences. - What role does feminism play in redefining art culture in Pakistan?

Feminism reshapes artistic culture in Pakistan by opening spaces for women’s voices, highlighting gender norms, and expanding visual dialogues around identity, agency, and social justice. - Is Pakistani feminist art connected to activism?

Yes — many feminist artworks cross into activism by addressing societal inequalities, demanding visibility for women, and reinforcing feminist principles through creative expression. - How does Pakistani feminist art differ from Western feminist art?

While sharing core themes of gender equality, Pakistani feminist art often blends local cultural signifiers, histories, and socio-political contexts, giving it a distinct voice that is rooted in Pakistan’s own cultural and historical realities. - Where can someone explore Pakistani feminist art?

Contemporary feminist art by Pakistani women can be experienced through online galleries, cultural festivals, exhibitions, and publications documenting works by artists like Shehzil Malik and Maliha Abidi — helping popularize their art locally and globally.